The last time Americans faced an economic crisis, it was called a "Mancession." As millions of people lost their jobs in the Great Recession, 70 percent were men, many in construction and manufacturing.

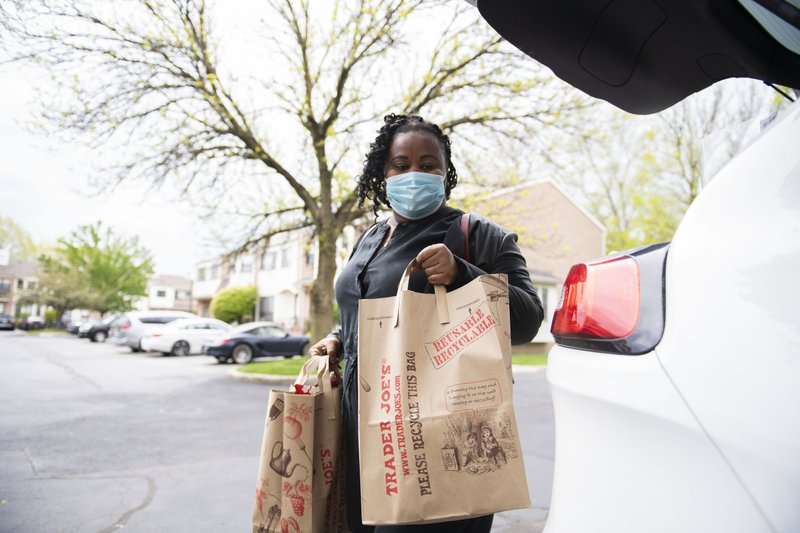

This time, as job losses linked to the coronavirus pandemic dwarf what the country experienced in the 2007-09 crisis, the heaviest toll is falling on women.

Waitresses, day care workers, hairstylists, hotel maids and dental hygienists are among the 20.5 million people who watched their jobs vanish in April -- the most devastating spike in unemployment since the Great Depression.

"I had a good rhythm going. I wasn't rich, I couldn't complain saying I was poor," said Ilanne Dubois, a 36-year-old single mother in Long Island who worked as a waitress at a Manhattan hotel. "Now, all of that stability is gone. We're falling into a hole."

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

Women have never experienced an unemployment rate in the double digits since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began reporting data by gender in 1948 -- until now. At 16.2%, women's unemployment in April was nearly 3 points higher than men's, according to Labor Department rates released Friday. But a closer look at the numbers shows deeper disparities.

Not only are women overrepresented in some of the hardest-hit industries, such as leisure and hospitality, health care and education, but women -- especially black and Hispanic women -- lost jobs in those sectors at disproportionate rates.

Before the pandemic, women held 77% of the jobs in education and health services, but they account for 83% of the jobs lost in those sectors, according to an analysis by the National Women's Law Center. Women made up less than half of the retail trade workforce, but they experienced 61% of the retail job losses. Many of these women held some of the lowest-paying jobs -- the cashiers, hotel clerks, office receptionists, hospital technicians, teachers' aides.

The pandemic has wiped out the job gains women made over the past decade, just months after women reached the majority of the paid U.S. workforce for only the second time in American history.

"How are we supposed to ever come back?" said Jasmine Tucker, director of research at the National Women's Law Center. "I think it's going to take a really long time to even reach that point again. A lot of people are going to be stuck."

Labor experts worry that even as states reopen, many workers, especially in leisure and hospitality, will continue to suffer cuts to hours, wages and tips. Low-wage workers, who are disproportionately female, will be the least likely to be rehired, economists say.

Even when men experienced the greatest initial job losses during the Great Recession, women took much longer to recover. Between June 2009 and June 2011, women lost 281,000 jobs while men gained 805,000. Those losses were driven by public-sector job cuts.

As local and state governments slash their budgets in the coming months, government workers will face painful job losses, and those will affect more women, who hold nearly 58% of public-sector posts, said Betsey Stevenson, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan. Many of these jobs are in public schools.

"That's only going to make things worse for women," Stevenson said.

Working mothers face an especially daunting recovery because they rely on schools and day care centers that remain closed. Even if hotels, restaurants and stores reopen, some women might not be able to find the child care necessary to return to work.

"If summer camps don't open up, if schools don't open in the fall, who goes back to work?" Stevenson said.

Many women were already barely bringing in enough money to cover child care costs.

"Now let's just add in the fact that your job just got a lot more dangerous," Stevenson said. "You're sending your kid to child care, where you're also risking you might get sick. You start doing all that math, and it just doesn't make sense anymore."

A Section on 05/10/2020