WASHINGTON -- Many Medicare recipients would pay less for insulin next year under a deal President Donald Trump announced Tuesday.

"I hope the seniors are going to remember it," Trump said at a Rose Garden ceremony, joined by executives from insurance and drug companies, along with senior citizens and advocates for people with diabetes.

"We have reached a breakthrough agreement to dramatically slash the out-of-pocket costs of insulin," Trump said during the late-afternoon event. "You know what's happened to insulin over the years, right? Through the roof."

Medicare recipients who pick a drug plan offering the new insulin benefit would pay a maximum copay of $35 a month starting next year, a savings estimated at $446 annually. Fluctuating cost-sharing amounts that are common now would be replaced by a more manageable sum.

The insulin benefit will be voluntary, so during open enrollment this fall, Medicare enrollees who are interested must make sure to pick an insurance plan that provides it. Most people with Medicare will have access to it.

Nearly half of all eligible Medicare Part D and Medicare Advantage plans will offer this, Trump said. Some plans may even choose to offer insulin at no cost, he added.

Stable copays for insulin are the result of an agreement shepherded by the administration between insulin manufacturers and major insurers, Medicare chief Seema Verma told The Associated Press. The three major suppliers, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, were all involved.

"It was a delicate negotiation," Verma said. Drugmakers and insurers have been at odds in recent years, blaming one another for high prices. "I do think this is a big step."

If the model is successful, the administration will consider expanding it to other "high-cost drugs," Verma said in a call with reporters. The model is projected to save the federal government $250 million over five years.

BIG WORRIES

The cost of insulin is one the biggest worries for consumers generally concerned about high prices for brand name drugs. Millions of people with diabetes use insulin to keep their blood sugars within normal ranges and stave off complications that can include heart disease, blindness, kidney failure and amputations. People with diabetes also suffer worse outcomes from covid-19.

On Tuesday, Trump suggested that former President Barack Obama was responsible for high drug prices. And he took a dig at former Vice President Joe Biden, who's running to deny him a second term. "Sleepy Joe can't do this," Trump said.

The president last week told Republican senators at a Capitol Hill meeting that he still wants to pass a bill this year to lower drug costs, saying "I think you have to do it," according to a summary from an attendee. Bipartisan legislation to limit price increases and reduce costs for older people with high drug bills is pending in the Senate.

But the fate of any drug pricing bill seems to rest with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who has a much more ambitious plan for Medicare to negotiate prices for the costliest drugs, not just insulin. Pelosi would use expected savings to provide vision, dental and hearing coverage for older adults. Most Republicans oppose that approach as an expansion of government price-setting.

Although the White House and Pelosi's office were in conversations last year about action on drug prices, the relationship between the two leaders has been tense for months.

White House Counselor Kellyanne Conway told AP that the administration can't wait for the Democratic-controlled House on drug prices. "Waiting for them to act is very perilous," Conway said.

"We just continue to fight for seniors," Conway said on a call with reporters. "This is a president who promised as a candidate that he would, quote, 'not touch Medicare or Social Security.' He's touched it in the right way."

AVAILABLE PLANS

Verma, head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said 1,750 insurance plans that offer drug coverage to Medicare recipients have agreed to provide insulin for a maximum copay of $35 a month next year. It will be available through "enhanced" plans that may cost more per month but offer additional benefits such as reduced cost-sharing on certain drugs. The cap on copays is expected to lead to a small increase in premiums.

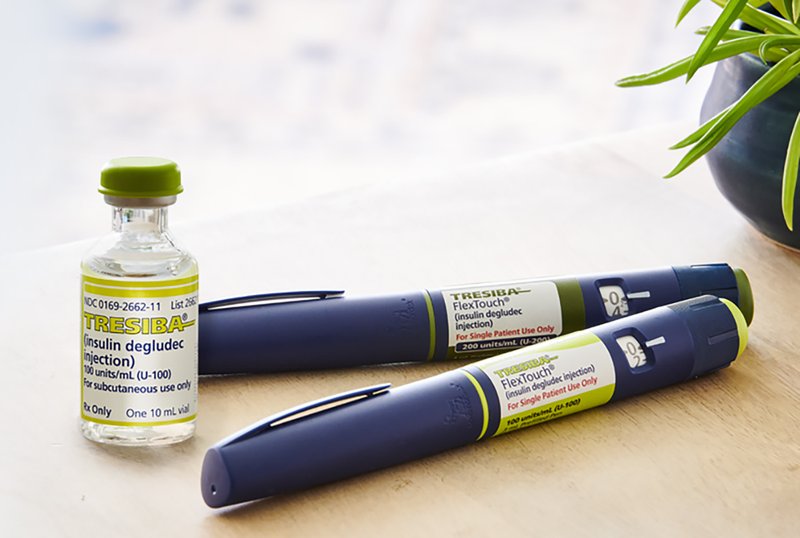

Importantly for patients, the new benefit would cover a range of insulin products, including pen and vial forms for rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting and long-acting versions.

One out of three people with Medicare have diabetes, and more than 3 million use insulin. At list prices, the drug can cost more than $5,000 a year. Although insured patients don't pay that, they do notice rising copays that are based on the full cost. People who can't afford their insulin may try to cope by reducing their doses, a dangerous calculation that can put their lives in jeopardy.

Medicare's prescription drug benefit is offered by private insurers, either as a stand-alone "Part D" drug plan added to traditional Medicare, or as part of a managed care plan under Medicare Advantage. The taxpayer-subsidized private plans are closely regulated by the government, but by law Medicare is barred from negotiating drug prices.

Insurers and drugmakers welcomed the announcement. The industry group America's Health Insurance Plans called it an "excellent example of public-private partnerships where everyone wins." The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America said it's pleased to see the administration focused on lowering out-of-pocket costs for patients.

Medicare estimates that about six in 10 beneficiaries are already in prescription drug plans that will offer the new insulin benefit. Those whose plans don't offer the new option can switch during open enrollment season, which starts Oct. 15. Medicare's online plan finder will help beneficiaries find plans that cap insulin copays.

The model will take effect Jan. 1. Plans will be in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, Verma said. Participation is voluntary for insurers and Medicare recipients alike.

Premiums increases are expected to go up $1 to $2 per month for enhanced Part D plans because of this model, Verma said.

AT ODDS

Before the pandemic, Trump and his administration were focused on lowering drug prices, which consistently polled as a top concern -- especially among older voters.

Trump embraced and regularly touted traditionally Democratic ideas to lower prices, including allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers and proposing an international pricing index that would base the price of some Medicare drugs on the lower prices paid in other countries.

Little came of those efforts, however, as Trump's advisers, and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar regularly feuded over the best policies to lower prices.

The Trump administration had begun moving forward on a proposal late last year to allow states, drug wholesalers and pharmacies to import some cheaper drugs from Canada, though officials did not say when the plan might go into effect.

Trump also embraced a legislative proposal from Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, and Ron Wyden, D-Ore., the committee's top Democrat, that would limit price increases in Medicare's prescription drug benefit to the rate of inflation or otherwise force companies to pay a penalty in the form of a rebate. It would also limit senior citizens' out-of-pocket drug costs to $3,100 a year.

Trump last week told Grassley at a Senate Republican lunch that he still wanted to move forward on the legislation, but it faces opposition from most Senate Republicans, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Information for this article was contributed by Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar and Hannah Fingerhut of The Associated Press; by Shira Stein of Bloomberg News; and by Seung Min Kim and Yasmeen Abutaleb of The Washington Post.

A Section on 05/27/2020