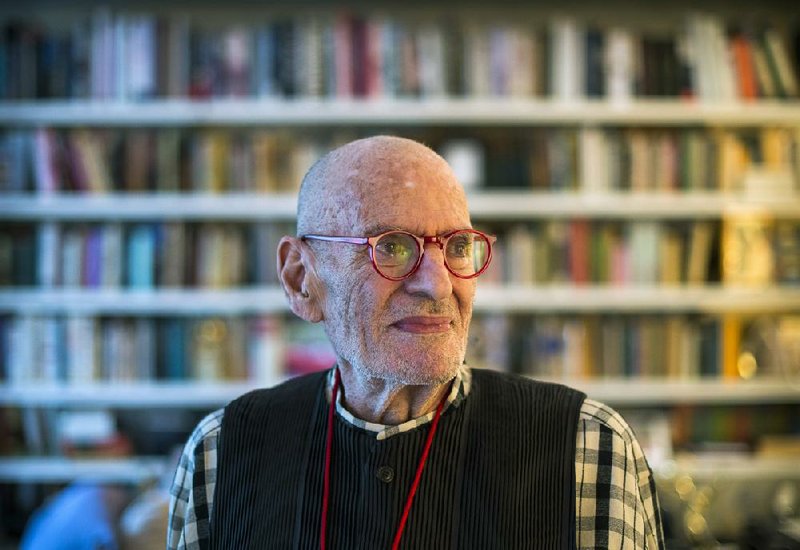

Larry Kramer, the noted writer whose raucous, antagonistic campaign for an all-out response to the AIDS crisis helped shift national health policy in the 1980s and '90s, died Wednesday morning in Manhattan. He was 84.

His husband, David Webster, said the cause was pneumonia. Kramer had weathered illness for much of his adult life. Among other health issues, he had been infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, contracted liver disease and underwent a liver transplant.

"We have lost a giant of a man who stood up for gay rights like a warrior. His anger was needed at a time when gay men's deaths to AIDS were being ignored by the American government," said Elton John in a statement.

An author, essayist and playwright -- notably hailed for his autobiographical 1985 play, The Normal Heart -- Kramer had feet in both the world of letters and the public sphere. In 1981 he was a founder of the Gay Men's Health Crisis, the first service organization for HIV-positive people, though his fellow directors effectively kicked him out a year later for his aggressive approach. (He returned the compliment by calling them "a sad organization of sissies.")

Kramer then became a founder of a more militant group, ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), whose street actions demanding a speedup in AIDS drugs research and an end to discrimination against gay men and women severely disrupted the operations of government offices, Wall Street and the Roman Catholic hierarchy.

"One of America's most valuable troublemakers," Susan Sontag called him.

Even some of the officials Kramer accused of "murder" and "genocide" recognized that his outbursts were part of a strategy to shock the country into dealing with AIDS as a public-health emergency.

In the early 1980s, he was among the first activists to foresee that what had at first caused alarm as a rare form of cancer among gay men would spread worldwide, like any other sexually transmitted disease, and kill millions of people without regard to sexual orientation. Under the circumstances, he said, "If you write a calm letter and fax it to nobody, it sinks like a brick in the Hudson."

The infectious-disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci, longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, was one who got the message -- after Kramer wrote an open letter published in The San Francisco Examiner in 1988 calling him a killer and "an incompetent idiot."

"Once you got past the rhetoric," Fauci said in an interview for Kramer's obituary, "you found that Larry Kramer made a lot of sense, and that he had a heart of gold."

Kramer, Fauci said, had helped him to see how the federal bureaucracy was indeed slowing the search for effective treatments. He credited Kramer with playing an "essential" role in the development of elaborate drug regimens that could prolong the lives of those infected with HIV, and in prompting the Food and Drug Administration to streamline its assessment and approval of certain new drugs.

In recent years Kramer developed a grudging friendship with Fauci, particularly after Kramer developed liver disease and underwent the transplant in 2001.

Looking back in 2017 on his early days as an activist, Kramer, frail but still impassioned, explained the thinking behind his approach:

"I was trying to make people united and angry. I was known as the angriest man in the world, mainly because I discovered that anger got you further than being nice. And when we started to break through in the media, I was better TV than someone who was nice."

Laurence David Kramer was born on June 25, 1935, in Bridgeport, Conn., the second son of George and Rea (Wishengrad) Kramer. George Kramer had earned undergraduate and law degrees from Yale University but was unable to make a decent living during the Depression. Rea Kramer supported the family by working in a shoe store and teaching English to immigrants.

After graduating from Yale in 1957 and serving a tour in the Army, he worked in New York, first for the William Morris Agency and then for Columbia Pictures.

He got into AIDS work in the summer of 1981 after reading an article about deadly cases of a rare cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, among young gay men.

The urgency of his life found its way into his plays. The Normal Heart, which opened at the Public Theater in April 1985 and ran for nine months, was a passionate account of the early years of AIDS and his campaign to get somebody to do something about it.

He was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay for Women in Love, the 1969 adaptation of D.H. Lawrence's novel. It starred Glenda Jackson, who won her first Oscar for her performance.

He also wrote the 1972 screenplay Lost Horizon, a novel, Faggots, and the plays Sissies' Scrapbook, The Furniture of Home, Just Say No and The Destiny of Me, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1993.

At the time of his death, Kramer was working on a play called An Army of Lovers, which he was updating to include the pandemic.

At the 2013 Tonys, he was honored with the Isabelle Stevenson Award, given to a member of the theater community for philanthropic or civic efforts.

Information for this article was contributed by Mark Kennedy, Hillel Italie and David Crary of The Associated Press.

A Section on 05/28/2020