We hadn't quite been married a year when we bought a house in west Little Rock, a three-bedroom, two-bath job with a cathedral ceiling in the living room that would frustrate any attempts at air conditioning.

It was relatively new construction, but the first owners' taste wasn't entirely congruent with ours, so we had wallpaper stripped off and walls painted.

We painted the baseboards ourselves, dripping two-inch brushes into eight-ounce cans of Sherwin Williams' Neighborly Peach and sliding it up and down a four-inch range, starting on opposite sides of the room and slowly scooching toward one another on our butts.

In the middle of the room, which was to become Karen's office, there was a cheap boombox, the kind that combined an AM/FM radio with cassette and CD players. That's how we first heard Tom Petty's "Wildflowers."

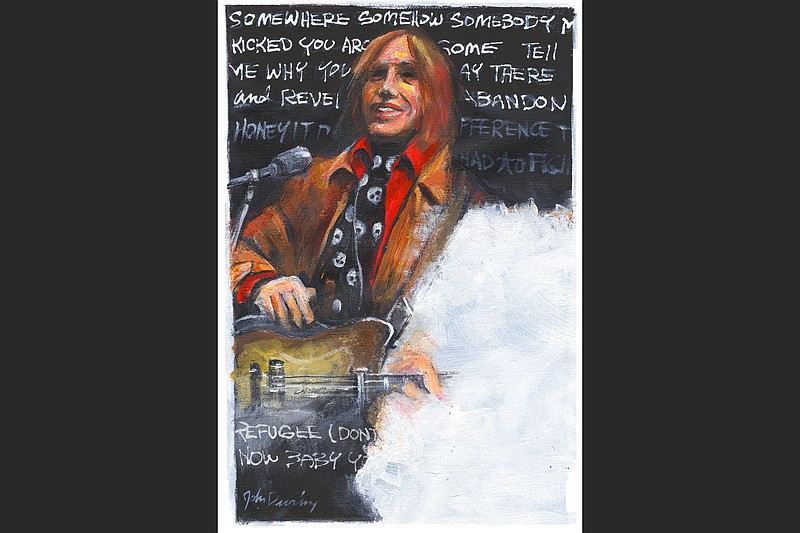

We played it over and over, like people sometimes did with new records back then. We learned it, we absorbed it. We were both fans. I'd picked on T.P. and the Heartbreakers early — their first album, "Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers," had come out in November 1976. It immediately became a favorite, a supposedly "new wave" act that felt more like a repudiation of the corporate competence of bloated faceless bands like Journey and Styx than the acting out of the Sex Pistols and other arty and contrived punks.

Here was revolution within the system, marked by economical singles and emotional urgency. Songs such as the Byrds-like "American Girl" and the Stones-ish "Breakdown" felt like a new covenant, a refreshment of faith in guitar-based rock 'n' roll.

And Karen is from Cleveland, home of WMMS-FM; the rock is strong in this one.

So you could have played the scene for irony: Tom Petty as the soundtrack of suburban home improvement. And it wasn't just a young couple listening while going through the motions of responsible adulting — the record was adult as well, like Bob Dylan's "Blood on the Tracks," an album about how success couldn't insulate you from pain, about how it was possible to love what was slowly killing you.

"It's good to be king and have your own way," Petty sang in "It's Good to Be King," repurposing the line from Mel Brooks. "Get a feeling of peace at the end of the day."

But Petty made it clear he wasn't king, despite what we might have thought about his rock 'n' roll lifestyle. He'll be king "when dogs have wings." "Wildflowers" is a melancholy record — a bittersweet, gingerly mounted thing that at times feels diaphanous. Other times it growls and darkly moans.

Petty was 44 when "Wildflowers" came out, and from the beginning it was to be a solo album, credited to him alone, not him and the Heartbreakers. That was enough to cause tension. Petty wanted to see other musicians, much the same way Bruce Springsteen had taken occasional sabbaticals from the E-Street Band.

In 1989, he made "Full Moon Fever" with the help of fellow Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne, and though all the Heartbreakers except drummer Stan Lynch made appearances on the album, the end result is somewhat glossier and deeper than the Heartbreakers' typical grit sound. Lynne made "FMF" more Beatle-ly, layering on keyboards and backing vocals.

Although the songs still fit easily within the Heartbreakers' repertoire, Lynch balked at playing them in concert because, he said, they made him feel like he was "in a cover band." Heartbreakers keyboard player Benmont Tench and bassist Howie Epstein might have felt similarly slighted. Tench played piano on a single track while Epstein added backing vocals to two.

While guitarist Mike Campbell was fully involved in "Full Moon Fever" and was credited as a producer along with Petty and Lynne, the implication was clear. Petty was a viable solo artist, and while the Heartbreakers might have been the American analog to the Rolling Stones, he wasn't going to be constrained from operating outside their context.

ORIGIN STORIES

There a couple of versions about how "Wildflowers" came to be.

Version one has it starting with producer Rick Rubin, who after establishing himself in the realms of creative and business for with hip-hop label Def Jam in the '80s, began to branch out and work with other artists (notably Johnny Cash, with whom he'd record "America Recordings" during breaks from the "Wildflower" sessions). He was a fan of "Full Moon Fever" and contacted MCA, Petty's label at the time, about the possibility of working with him.

When Petty moved to Warner Bros. in 1989, label president Mo Ostin brought Rubin and Petty together. They hit it off and decided to do an album together.

"I think Rick and I both wanted more freedom than to be strapped into five guys," Petty told Paul Zollo for the 2005 book "Conversations With Tom Petty."

"We wanted to be able to do whatever we wanted ... as far as bringing in this guy or that guy. With a Heartbreakers' record, you can't bring in a different bass player or a different drummer. So I wanted that freedom, and we did play with a lot of different musicians, and we even did a lot of trial and error with different musicians, auditioned people for the record."

But Petty told his biographer Warren Zanes a slightly different story.

"It was another time of change for us. It was clear that Stan was unhappy. He was unhappy and I think that what finally tore it apart for me was that Stan told Mike [Campbell] something about not liking the material I was writing. He didn't think it was what he wanted to be doing. I figured there's no point in making someone play something they're not into in the first place, and we'd been having our differences — 20 years with somebody, it's tough."

So Rubin brought in drummer Steve Ferrone, and "Wildflowers," while it employs a lot of outside musicians (including Ringo Starr on drums on "To Find a Friend," the only cut Ferrone doesn't play on) is really a Heartbreakers' record minus Lynch. And since Ferrone would join the band the following year, it might be seen as the first Heartbreakers 2.0 record, despite Petty's assertion about not wanting to be tied to the band.

A DIFFERENT PRODUCT

In any case, most people probably don't distinguish between Petty's solo work and his work with the Heartbreakers, though there is something about "Wildflowers" that marks it as a different kind of product.

Petty's songwriting was always strong, but on "Wildflowers," it seems to kick up a level. There's not a weak track on the original record, a single CD that runs 62 minutes (compare that to 1979 "Damn the Torpedoes," the other leading contender for best Tom Petty record ever, which clocks in at 36 minutes and 38 seconds) and might serve as the summation of where Petty and the Heartbreakers fit in the continuum of American pop music.

There's pop, rock and blues on this record, stripped down in accordance with Rubin's signature style but relaxed and expanded, unfolding in a casual context far removed from the Heartbreakers' usual grind and clash.

It opens with the title track, which Petty contended arrived fully formed, a three-chord folk ballad for which he improvised lyrics on the spot. That's followed by the Dylanesque shrug of complaint "You Don't Know How It Feels," jaunty road song "Time to Move On," anthemic "You Wreck Me," "It's Good to be King," etc.

Here Petty's songwriting comes to the front, and he reveals himself as gentle, sardonic and bruised, a grown-up artist at midlife, someone who understands how lucky he's been and how much he's lost.

Petty famously had too much material for the album. He'd spent nearly two years writing songs in his backyard studio. He originally proposed a 25-track double CD, but commercial considerations thwarted that. So he gave "Leave Virginia Alone" to fellow Warner Bros. artist Rod Stewart for his "A Spanner in the Works" LP. "Girl on LSD" showed up on the B-side of the "You Don't Know How It Feels" single. "Climb That Hill," "Hung Up and Overdue," "Hope You Never," and "California" appear in different forms on the soundtrack album Petty did for the 1996 romantic comedy "She's the One."

A lot of them went into the vault, to be dragged out eventually because vaults aren't tombs but storage lockers and will inevitably be opened up and picked through.

GREATER AND LESSER

"Wildflowers" is an expansive and wistful thing. The new "Wildflowers and All the Rest (Deluxe Edition)" is overwhelming. It might be interesting for obsessives who feel compelled to investigate the creative process, but at the same time — by showing us around the sides of the original album — it drains away a bit of the magic.

So, as usual, the new deluxe product re-issued in commemoration of the original feels both greater and less than the original, and whether you need it probably depends on how you relate to old records.

It's available in multiple formats, from a $500 "ultra deluxe edition" nine-LP version, a $250 nine-LP version, a $175 seven-LP version ($174.74), a $150 five-CD version, a $50 four-CD version, a $40 three-LP version, and a $20 two-CD version. All the tracks are also available as a digital download.

It's obviously unnecessary, especially since anyone with a Spotify subscription might access any of its 54 tracks at will (or at random, considering how we use these devices) though it's best to listen to the whole thing at one time, paying special attention to the collection of 14 of Petty's home recordings and noting the sometimes tiny, canny tweaks eventually made to these songs in progress. (In the collection's liner notes, Campbell talks about how Petty worked the generic lyric of a song originally called "You Rock Me" into the devastating "You Wreck Me.")

"Wildflowers and All the Rest" is best received as an aural documentary about the making of one of the signal albums of the 1990s, and one of Petty's best works. It was, reportedly, his favorite, and he'd often talked about bringing out an expanded version.

On the other hand, there is a temporal dimension to these artifacts and souvenirs, and hearing "Wildflowers" in 2020 is uncanny. It's not the same record it was, just like "Rubber Soul" and "Blue" aren't the same as when we first heard them. Tom Petty has been dead since 2017; no doubt those old baseboards have been painted a few times since then.

"Wildflowers" might take me back to November 1994, to where paint fumes and carpet nap and strummed acoustic guitars snarl up in my memory, but I can't take anyone else there.

- Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com

- blooddirtangels.com