BOSTON -- Students in many U.S. schools are now learning a more complex Thanksgiving lesson that includes conflict, injustice and a new focus on the people who lived on the land for hundreds of years before European settlers arrived and named it New England.

Inspired by the nation's reckoning with systemic racism, schools are scrapping and rewriting lessons that treated American Indians as a footnote in a story about white settlers. Instead of making Pilgrim hats, students are hearing what scholars call "hard history" -- the more shameful aspects of the past.

Students still learn about the 1621 feast, but many are also learning that peace between the Pilgrims and American Indians was always uneasy and later splintered into years of conflict.

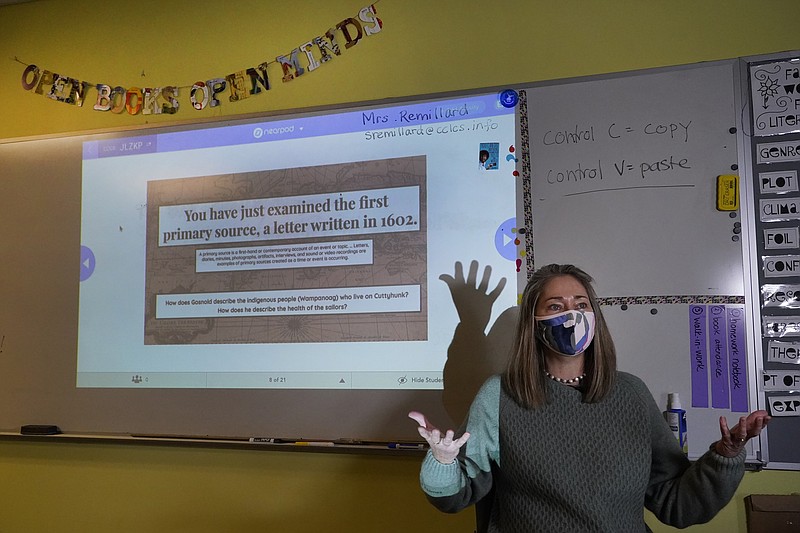

On Cape Cod, language arts teacher Susannah Remillard long found that her sixth grade students had been taught far more about the Pilgrims than the Wampanoag people, the American Indians who attended the feast. Now she's trying to balance the narrative.

She asks students to rewrite the Thanksgiving story using historical records, and then she asks them to write a poem from the perspective of a person from that time, half settlers and half Wampanoag.

"We carry this Colonial view of how we teach, and now we have a moment to step outside that and think about whether that is harmful for kids, and if there isn't a better way," said Remillard, who teaches at Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School in East Harwich, Mass. "I think we are at a point where people are now ready to listen."

Students as young as kindergarten are now being taught that harvest feasts have been part of Wampanoag life since long before 1621, and that thanksgiving is a daily part of life for many tribes.

They're also being taught that the Pilgrims and Wampanoag were not friends, and that it's important to "unlearn" false notions around the feast.

"We don't want the coloring books of the Pilgrims and the Native Americans," said Crystal Power, a social studies coach. "We want students to engage with what really happened, with who lived here first, and to understand that there was no such thing as the New World. It was only new from one side's perspective."

Advocates for Indigenous education caution there's still much to improve. Change has been slow and spotty, they say, and many schools cling to insensitive traditions, including costumed dramas and paper headdresses.

"Progress seems to be gaining momentum, but there's still a lot of work to do," said Ed Schupman, manager of Native Knowledge 360, the national education initiative at the National Museum of the American Indian, and a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma. "Change is still needed, and it has only been significant in some places."

Although schools say parents have mostly embraced the changes, they acknowledge it can be polarizing. Prominent lawmakers have resisted efforts to rethink Thanksgiving, including Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., who last week blasted "revisionist charlatans of the radical left."

"Too many may have lost the civilizational self-confidence needed to celebrate the Pilgrims," Cotton said.

School officials say they aren't changing history, but adding parts that have been left out. Standard social studies textbooks have included little about American Indians, and alternatives were long elusive. Teachers say that's changing, thanks to native scholars who have written children's books, lesson plans and other materials.

In Massachusetts this year, every public school is getting copies of a new state history book co-written by a Wampanoag author and historian. The book was published to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower's arrival, but it notably begins thousands of years earlier, with the history of the Wampanoag people.

Many schools are also adding lessons on native cultures through the year, including around Columbus Day, which some districts now mark as indigenous Peoples Day. More are also looking for ways to bring Indigenous voices directly into the classroom.