With about a month remaining before a federal moratorium expires on many evictions for nonpayment of rent, housing advocates fear a January spike in Arkansans losing their homes and adding to homeless and covid-19 case numbers.

Landlords and property managers filed 1,339 of the most common type of evictions in Arkansas courts, unlawful detainer lawsuits, from Sept. 1 to Nov. 20 this year, according to state court online data examined by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

That's up by 53 cases from the same period last year.

Not all courts file cases online, and evictions also may be filed under two other statutes, including Arkansas' criminal eviction law. The number also does not include evictions that happen outside the courts, which experts said they've seen go up since an initial decrease immediately after the federal government published its mandate.

Calls from renters facing eviction generally are "continuing to be very high, and I anticipate that when the CDC order expires in January, we'll probably see even more," said Kendall Lewellan, a managing attorney with the nonprofit Center for Arkansas Legal Services.

She added that over the past month, the center has gotten "well over double" the normal number of calls it receives about evictions at this time of year.

Experts and advocates nationwide have called for more rental assistance from the government, saying that keeping people in their homes is critical to protect public health and that landlords should have a way to receive money owed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Sept. 4 issued its ban on evictions for nonpayment of rent for tenants who meet certain conditions. The order expires Dec. 31.

The moratorium's stated goal was to decrease cases of covid-19. The idea was to keep tenants who qualify from losing their rental housing and being forced to enter congregate settings such as homeless shelters or homes of friends or family members, increasing the likelihood of virus exposure.

That's what Kimberly Peters, a Little Rock renter, was trying to avoid for herself and her two teenagers when she sent a message to Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge's office in August. The Democrat-Gazette obtained the document under a public records request.

Peters lost her job at a local nonprofit in March because of the pandemic, soon after she moved into her downtown Little Rock apartment, she said in an interview.

She wasn't able to make rent until she found another job in May. Her unemployment check was delayed. Her car, which she needed to get to work, was repossessed briefly.

As bills stacked up, she could make only a partial rent payment. She asked to set up a payment plan and to clean apartments to make up the difference.

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

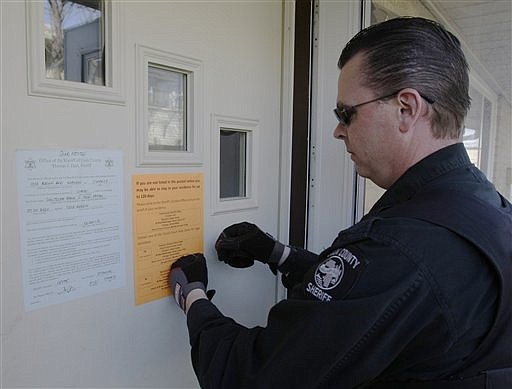

Her landlord said no, and put an eviction notice on her door in April, then in May, June and July, she said. In September, she turned in the CDC moratorium's declaration form to stop the eviction. Still, she got another eviction notice later in September and again in October.

"That was very stressful to come home to those eviction notices -- not knowing whether I was going to be able to make those payments," she said. "I wanted to keep a roof over my children's heads."

To her knowledge, no eviction lawsuit or charge was ever filed against her in court.

Unsure what would happen when the federal eviction ban no longer applies and unwilling to keep piling up debt and late fees, Peters decided to move. It was hard to find a landlord who would accept her because she was upfront about what happened at her last apartment. She also wanted to find a landlord who would work with her if she experienced another income loss.

For now, she's working two jobs and trying to stay ahead of payments.

"I'm blessed," Peters said of her new place. "People are still losing jobs. It's a horrible situation, and people are being evicted and losing their homes."

Peters was one of a handful of tenants since the pandemic began who have filed complaints about threats of eviction or actual evictions that occur outside the courts -- called self-help evictions. These evictions are illegal and often involve measures such as shutting off utilities, including electricity, or locking tenants out of their homes.

An August complaint to Rutledge's office from a Booneville woman described how "they came to the house, took the back door off the hinges and then the front door off the hinges and laughed about it after I told them that was illegal." She "said they had done it before."

A Trumann renter complained in September that after "an extremely derogatory conversation," the landlord said "he will not start an eviction, but rather come over and disconnect utilities in an effort to get me to pay or move out."

Lewellan said calls to the nonprofit for assistance to deal with self-help evictions have started to pick up after an initial drop when the moratorium was first announced.

"I think that it's harder right now for landlords to go through the proper channels to evict someone, so it might be more tempting to go through improper channels," Lewellan said.

The federal moratorium on evictions has offered protection to renters in Arkansas, experts say. A copy of the declaration is available through Arkansas Legal Services at: arlegalservices.org/node/1075/cdc-issues-federal-eviction-moratorium.

In most cases, if tenants know to fill out the CDC declaration and include that declaration in their responses filed in court, then it works to stop the eviction, said Lynn Foster, a retired University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law professor who specializes in housing issues. But, she said, many tenants who appear to qualify, based on information included in responses, never mention the moratorium.

That leads her to the conclusion that many don't know about the ban.

Neil Sealy, an organizer with Arkansas Renters United, said he thinks more renters with low incomes know about the order because of community outreach efforts by various organizations. But there are still many who don't understand their rights under the moratorium.

"A lot of people still don't know what the declaration is," Sealy said. "I would say probably more people don't know about it than do."

His group is going back to check on tenants it's worked with since May to see if they need more help and ensure they know about rental assistance available in Arkansas before the looming end of the moratorium.

"It's never a good time to be evicted, but in January, it's especially bad," he said. "I'm not optimistic."

Foster said she, too, was concerned about evictions and homelessness in January.

"I assume what you're going to see is an increase in homelessness and more demand from homeless shelters across the state," she said. "Worst-case scenario, you're going to see more deaths because people are going to be made homeless during a pandemic."