Hot Springs is a place with many handles.

For carousers it's "The City of Visitors," for Al Capone it was simply "Bubbles," for the Caddo Indians it was the "Valley of Vapors." Take your pick. Each nails down a small Southern town fast to a mountain like a volcano now extinct. A fly-over reveals a green hillside leaking rivulets of boiling waters running out at 148 degrees. People have always believed in their magical powers. It takes some 4,000 years to sink down and only a year to bubble back up — hence, "Bubbles" seems apt, or maybe "Vapors" is best after all — the stuff of countless dreams evaporating over it like a silver mist.

In reading David Hill's marvelous book about the place, "The Vapors," a 1947 meeting he mentioned came to mind. My father, Sid McMath, was the newly elected prosecuting attorney of Garland/Montgomery counties having ridden in on the reforming wave of the "GI" (Government Improvement) Party. As its leader, dad promised to "clean up Hot Springs!"

The corrupt machine of Mayor Leo P. McLaughlin and Municipal Judge Verne Ledgerwood was defeated, so the survivor, crime boss Owney Madden, wanted to talk. He called for a meeting, said he would come out to our little place in the country, a short ride from town on Cedar Hill Road. Anne, 26, my mother, my brother Sandy, 5, and this writer, an infant, were inside. Dad recalls it vividly in his memoir "Promises Kept." Thinking Madden might have something important to say about the Mob, he agreed to see him near the front gate.

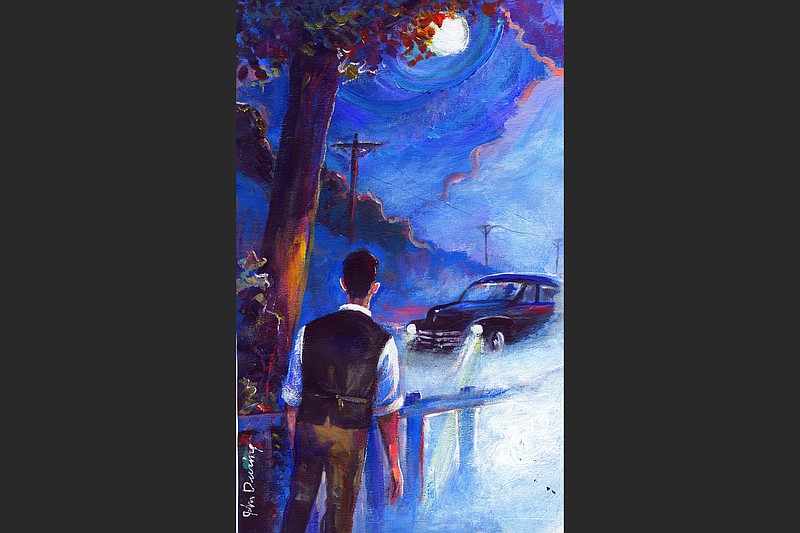

In the dark on a small hill just outside our fence, the black limo slowly crunched the gravel to a stop. It idled into silence, its lights hesitating before flicking off, sitting there, an invisible, menacing presence. Dad, alone, walked toward it with a flashlight, unarmed, wondering if he had made a mistake. After all, Madden's nickname was "the Killer." He was said to have murdered at least seven in New York and had been shot 11 times for his pains. He did two prison tours in Sing-Sing and, when paroled, was exiled to Hot Springs.

What inscrutable fate, what fostering star could possibly have brought these two utterly different men so very far, Sid McMath and Owney Madden, to meet that night on a lonely rural road in Arkansas?

■ ■ ■

Madden was a spiffed-up, handsome English hood whose fires had been lit by Lancashire coal on the Liverpool docks till in 1902, as a boy of 10, he found his way to America to be cooked up hard in Manhattan's "Hell's Kitchen." He was just a working class Limey with a button-down cap and a weakness for "respectability," bribing boxers, bringing out babes, selling booze and promoting Black jazz. In New York he owned The Cotton Club, The Stork Club and the Silver Slipper, which featured Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday enthralling a "whites only" crowd. Implicated in the murder of Vinny "Mad Dog" Coll, Madden was back in the slammer until freedom found him on the road to Garland County.

By 1936 he settled into a cozy little deal with the locals: McLaughlin and Ledgerwood ran the politics while clever W.S. Jacobs ran the games and Madden ran the Mob, keeping them close but distant. It worked great. Owney had the magic touch; he picked up the pace and before long rich tourists, movie stars, fighters, big-name gamblers and politicians started pouring in. They came for the racetrack, the dice, the cards, the roulette, the women and the thermal baths.

Hot Springs was America's new place — Hot Springs was illegal and corrupt but so what? It was really, suddenly, truly red-hot! There is always an empty street Sunday morning sadness when it's over, but boy was it fun the night before! Hot Springs knew what she wanted. She didn't hesitate, she stepped out as a high-class redneck femme du monde — the same old sexy gal but sporting a brand new sophisticated dress.

Judges, cops and City Hall were all for sale; juries got rigged and elections riveted, nailed down, adjusted, the dead voted at least twice while the bagmen, bullies and bouncers poured out of the bars, bathhouses and brothels as poll watchers to do the multiple ballot thing and brag "I voted!"

Then the bills came due. Jacobs was dead and a new post-war generation had seen enough. Things were changing. The old game was broken up.

■ ■ ■

From a different direction came Sidney Sanders McMath. He was born on Flag Day, June 14, 1912, in a dogtrot cabin in south Arkansas. His grandmother, Lula Mae Rudd McMath, delivered him, and then set Sid aside to die. He refused. His father, Hal McMath, better known as Pap, said he was a fighter and he was right.

Lula Mae, whom everybody in the family called Mother Mae, was the daughter of a Confederate soldier. She liked to dance, played the hand harp, sang songs and dipped snuff. She said it was her "consolation."

She and her husband, Sidney Smith McMath, had eight children who saw adulthood. He was sheriff of Columbia County, a tough cookie, handsome, popular but with a mustachioed gunfighter stare. In 1911 he was killed battling bootleggers, leaving Mother Mae a poor widow who would never remarry. She survived at the McMath "home place," with a small cotton field, orchard, garden and smokehouse and lived into her 90s.

Sid's school was one room for all grades; they recited The Lord's Prayer, The Pledge of Allegiance and sang the song "Arkansas" before struggling through the "Three-Rs" (reading, writing and arithmetic). But school closed during harvest because the children were in the fields. Sid picked cotton when he was 8, got a penny a pound. On a good day, he made a dollar. He and sister Edyth would ride the mule into Magnolia to spend their loot.

But Pap was restless — he moved the family around. His horses, Cap and Dallas, pulled them to the Smackover Oil Boom in 1921. Harper, a little Black boy, followed crying he wanted to go too. It was winter and his bare feet were freezing and bleeding — so my grandmother, also known as Mother Mac, bandaged them and said, "Hop in." Sid always said that was the beginning of the Civil Rights movement.

The next year Pap moved them to Hot Springs. Sid arrived on his 10th birthday. The schools were great. Hot Springs High School was where he learned English, drama and debate. Urged to become an actor, he opted for politics instead — wanted "to make a difference," he always said.

He had seen the poverty, ignorance, the dirt and darkness, as well as Jim Crow, and promised he would make it all change. With the unquenchable "fire in the belly" of ambition, he would be governor or maybe more; would build roads, bring electricity, improve education, health care and fight racial injustice. He made a list of promises and Hot Springs was added on. What about gambling? Well, he found a serpent of corruption lurking beneath that alluring flower of glamour and gold.

He worked, sold papers and boxed to keep his corner. A year at Henderson, then he slipped on his Eagle Scout shirt and hitched to Fayetteville. With a law degree and a Marine commission, he was on his way.

Returning home, he practiced law, married his sweetheart, Elaine Braughton, Sandy's mother. Saw the war coming so Pearl Harbor found Captain McMath active in the Marines. Then Elaine died on their fifth wedding day. Sandy lived with his grandmothers while Sid went to war. He was a hero, fighting the Japanese, winning the Silver Star, Legion of Merit in the Solomon Islands and a "spot" promotion to Lt. Colonel on Bougainville Island.

Sick with malaria, he returned, was hospitalized, recovered and was stationed at Marine headquarters in Washington to help plan the invasion of Japan. There he met and married this writer's mother, Anne Phillips, a Mississippi cotton farmer's daughter, Congressional secretary and Miss Capitol Hill.

They came back to Hot Springs in 1945 and Sid led the political reform movement fueled by veterans known as the GI Revolt, proclaiming, "We fought for Democracy abroad and we thought we ought to have some at home."

■ ■ ■

Now Sid walked up to that black limousine waiting in the dark. He didn't get in. The driver turned on the lights. Things were tense. With Madden in front looking out the window, Sid saw the driver, built like a Sumo wrestler, smoking nervously, and two hoods in the back like movie gangsters sporting Fedora hats. Madden came to the point. Two cronies had robbed a jewelry store and he wanted the charges dropped. The soul is rarely sold all at once, but usually in little pieces. Sid thought. If he said, "Go to hell!" he might not see us again. So he said instead, "I'll think about it," and walked away.

The limousine sat there as if pondering something. Sid kept walking, a tingle crawling up his neck as he wrote later, like "he experienced during the war canoeing up a dark river on an island in the Solomons."

He never spoke with Madden again, sent the thieves to prison, closed the games, was elected governor and kept his promises. But that's another story.

Phillip H. McMath is a lawyer, Vietnam veteran and writer who lives in Little Rock.