Two scientists are racing

For the good of all mankind

Both of them side-by-side

So determined

Locked in heated battle

For the cure that is their prize

But it's so dangerous

— "Racing for the Prize," The Flaming Lips

James Bond, 007, is not coming to save us. We might get Wonder Woman at Christmas, or we might not. Normally around this time, I would be looking forward to a couple of months of Oscar-bait movies and a bunch of "For Your Consideration" award screeners. This year, there's really no fall movie season to preview.

More than seven months into this pandemic, I have resigned myself to there being no magic bullet. There will be no morning when we wake up to a cure, when our old normal suddenly returns. Most — some say 75% — of our restaurants and theaters will close. Most of our musicians will have to find some alternate way to feed themselves and their families. People have died, and though some people say some of those people would have died anyway, I can't help but feel sorry for the numbers and the ways we can push numbers away.

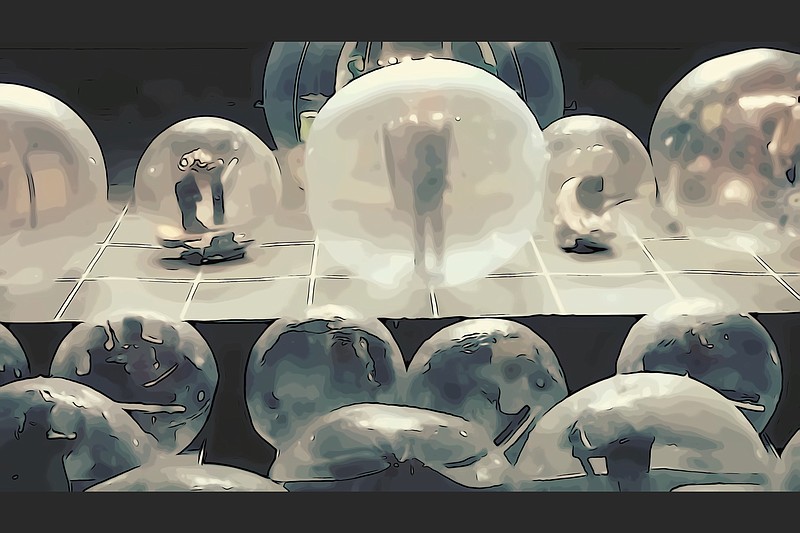

I saw where the Flaming Lips are planning a concert where everyone in attendance will be encased in their own plastic bubble. These are the days of miracle and wonder.

"No Time to Die," the next Bond movie, has been pulled from the release schedule, moved to Easter 2021. Maybe by then people will be coming back to the movies, maybe then there won't be seats taped off. But when this descended, we thought we might still be going to New York in late March for the Tribeca Film Festival.

"It's been the proverbial month of Sundays," said one of the socially distanced guests we had on our porch last night. "30 or 31 Sundays."

Someone else marveled at that antique phrase. She said she never knew exactly what it meant. Maybe, she thought, it meant four or five Sundays. But it's 210 — or 217 — days. Our lockdown started on March 12, the day after Rudy Gobert of the NBA's Utah Jazz tested positive for the coronavirus, setting off a chain reaction that saw all the major sports leagues shut down. That's when we knew it was serious; when it became apparent hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue would be foregone.

We have not felt much pain here in our bubble. We miss art gallery openings most of all, we have decided. And traveling, but not so much as we thought we would. We want to go to Paris, but not before it is Paris again. Most of Europe is out of bounds to us anyway, though not Serbia.

A few weeks ago a friend mailed in an absentee ballot and abandoned his Upper West Side apartment for Belgrade. He populates Facebook with photos of the city, the cafes and the bookstores. He plans on staying six months — more if necessary. He has the means to do that.

But we are all right here. A couple of weeks ago, our neighbors had a potluck dinner in the common area between our houses. We set up lawn chairs an appropriate distance apart, talked and laughed and drank wine and beer. But we never quite forgot the rules, we kept our distance from each other and raised our voices a little. We were good citizens, keeping the social contract.

We are scandalized by crowds. But part of me understands the impulse to rip off the mask and head for the beach, the lake, the clubs. Life is so very brief, and we ought not live in fear. Life is managing risk.

But the scolds are, for once, right: you don't do it for yourself, but for the grandmothers of strangers. And with our toys, it is not so difficult to substitute virtual community for the jostle and hum of in-person experience. Our screens are hi-def, our soundbars can rumble and scream. There is still content in the pipeline, and thousands of movies we still haven't seen.

A few weeks ago when my wife went upstairs to Zoom her book club, I found "The Harder They Come" on the Criterion Channel and watched the first hour or so, with the closed-caption subtitles turned on.

The caption writers couldn't understand the patois any better than I could, but both of us got the gist: A poor boy has no chance against the machine, but art offers a chance at transcendence. No one should be bored in a world where Shakespeare and Warren Zevon once lived and worked. We ought to be able to make do.

■ ■ ■

I'm leading a film class on Zoom for my friends at Lifequest of Arkansas.

So every Friday morning, I go upstairs to my home studio and struggle with technology. This is embarrassing because I like to think I'm competent with my devices, but it's more complicated sharing a film over Zoom than YouTube videos and tech blog entries would have you think. To paraphrase a recurrent bit of wisdom, Zoom is not supposed to know what app you're using when you share your screen. So you should be able to share programming from a website like Netflix or the output of your connected DVD player.

But, as Matthew Arnold told us, there is a difference between the world of theory and the world of practice. When I started my first class by trying to play Elia Kazan's "A Face in the Crowd" from my iTunes library, my 40-plus clients were treated to a black screen. Some heard the audio, but most did not.

Panicked, I switched to the backup DVD player connected to my computer. Another black screen experience. Finally, I limped through the three-hour class by showing YouTube clips from the film. (Quite by accident, I found an excellent 30-minute documentary on the making of the film that filled some time.)

Later we figured out that while it might be as easy as the bloggers and vloggers say to use Zoom when you are using a PC running Windows Whatever We're On or a Chromebook, it does not perform seamlessly with Apple products. In order to show films via Zoom from my rig, I had to first extract them from DVD via an open-source transcoder for digital files to a hard drive, then play them back through an open source cross-platform multimedia player.

That process is as difficult as it sounds, and limited the films I could show to titles I had on regular (not Blu-ray) DVDs, which required me to rethink what movies I'd be showing.

This disruption isn't insurmountable but is a lot different from what I'd do in a noncovid compromised world, which is take the DVD (Blu-ray or otherwise) down to Riverdale 10 and hand it over to a highly competent person who'd handle the screening from there. (Thanks to the ownership and management of the theater for helping us out all these years.) It was a lot easier when I didn't have to worry about muting and unmuting myself and clicking the proper boxes to share the film.

It was also easier to hold a conversation with 100 people gathered in a cinema than with 40-something boxes displayed in gallery view, a slight majority of which are black boxes of those who have declined to share their video (and I don't blame them for that; I went through school sitting in the back row with a baseball cap pulled down).

A video conference is not an ideal venue for the sort of discussions I like to lead; it's impossible to read a virtual room and people are naturally more reluctant to make offhand comments when they understand that to do so is to suddenly command the screens of everyone who has tuned in. There is a performative quality inherent in being isolated on a screen with which most people are initially uncomfortable. Like every documentary filmmaker knows, the presence of a camera changes things.

So we limp by, using the chat function, with me babbling on and on about how problematic people like Elia Kazan and Louis C.K. and even Leni Riefenstahl can make art that compels attention until I become aware of how ponderous I am sounding and beg for an observation or question that might put us back on a fruitful path.

The most telling difference between doing these classes live and doing them virtually is that when I'd do them live, some of us would stay for 10 to 15 minutes after class talking about the film. The Zoom classes are wrapping up a half-hour early.

Yet we are holding them, and maybe we are all getting better at living this way. I expect I'll continue using the technology even when/if things start getting back to normal. It's a tool I have added to my kit.

■ ■ ■

I still go to the office on weekends; usually, I am the only one there when I arrive. It is all right for the work, but I miss the chatter and the energy of the newsroom, the self-important hustle and the jocularity, the figurative (but only occasionally literal) backslapping. But even in the old days when I'd occasionally collaborate with another reporter, I wanted a few hours alone with a story. If I had to, I'd come up in the middle of the night to get that time.

I am getting more and more used to my bubble, this circumscribed world into which I selectively admit a few people, a few ideas, a few songs and movies. I am my own gatekeeper and can banish or cancel anything that does not fit comfortably into my worldview. The lure of snobbery is that we feel we can safely dismiss all that challenges our image of ourselves as well-rounded and reasonable creatures. We never have to contend with the blare of foreign beatboxes.

What I worry about is the loss of the accidental encounter, the decline of serendipity as we relax into our familiar habits of taste and thought. It's always been tempting to stay home when you've got a nice place, companionable cohabitants and a stocked pantry. You can cocoon with your classic rock and your nostalgia, watch "The Sopranos" and TCM.

What I worry about is the collapse of civic ritual. We have stopped going to weddings and funerals, to church services and ballgames. I don't know that, having stopped doing some things, we will automatically resume doing them once the lifeguards blow their whistles and tell us it is safe to go back in the water.

You don't really need a pandemic to crawl into your bubble.

- Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com

- blooddirtangels.com