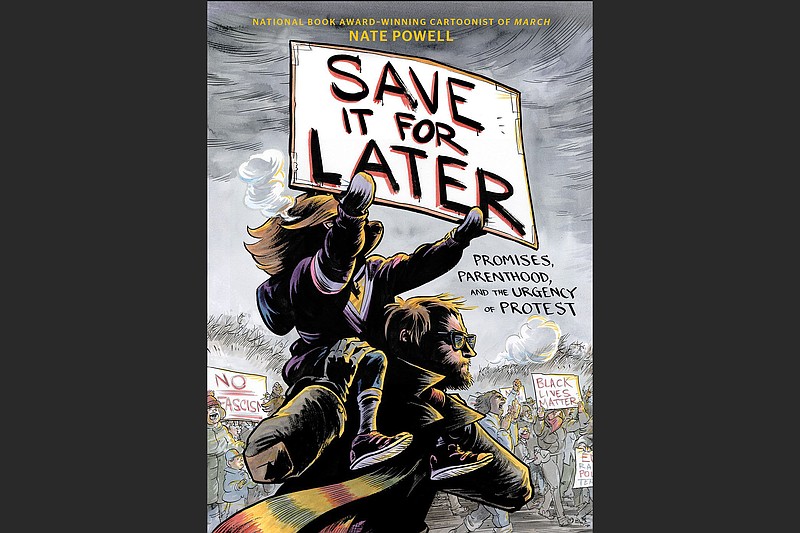

Early on in his new collection of comic essays, "Save It for Later: Promises, Parenthood and the Urgency of Protest," artist and writer Nate Powell and his two young daughters are watching TV at their home in Bloomington, Ind.

It is Jan. 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump's inauguration, and Powell's wife, Rachel, is attending the peaceful Women's March in Washington to protest the new president.

Powell and his daughters, Harper and Beverly, are watching coverage of the gathering.

Harper, 5 at the time, asks if they can have their own march.

And so they do. On the next page, the girls are marching through downtown Bloomington shouting "You've got to be fair" "We've got to stand up" and "No more bullies," as dutiful dad Powell follows, making sure they stay on the sidewalk.

In the text accompanying that full-page image, the 42-year-old Powell, who grew up in North Little Rock, concedes that this could be dismissed as a cute anecdote — 5-year-old girl and her sister protest on an empty street with her dad and sister, bless their hearts.

"But there was no march planned in my town that day, so my daughter founded one," he writes. "Three people deep, filling the air with their own chants for an hour, their own concerns as relative to the larger issues, but on their level, their own noise."

PROFOUNDLY THOUGHTFUL

This passage, in the essay "Hot Buttered Noodles," is in many ways the heart of "Save It for Later," Powell's visceral, emo- tional and profoundly thoughtful reaction to the past five years and which is published today by Abrams Comic Arts.

Through his fluid drawing style, creative page design and writing that is filled with sensitivity, intelligence and piercing observation — not only of what is going on around him but of himself — Powell confronts the maelstrom of American life since 2015, from the daily megaphone chaos of the previous administration to the never-ending war in Afghanistan, the growth of fascism, police violence against people of color, protests and the pandemic.

And all the while he's trying to help his children, presented in childhood innocence as anthropomorphic animals, work through their fear and anxiety and find their own voices.

Growing up, Powell was immersed in comics and underground punk rock, both of which informed his political sensibility.

"I started being a part of protest movements here in the mid-'90s," he says. "Reading 'The X-Men' is what gave me a social conscience. Punk and a lot of its attendant social and political focus, is what opened my eyes to the world as a 14- to 18-year-old."

NOT AN ACTIVIST

He doesn't call himself an activist, however.

"I'm like the vast majority of people. I show up and I use the time and energy from other parts of my life to make up for the fact that I'm less involved on a direct action level. A lot of that means putting my concerns and my heart and soul into the books I make."

In 2016 he won the National Book Award for his work on the third installment of the "March" trilogy, the graphic biography of the late civil rights activist and Georgia congressman John Lewis. He was the first comic artist to win the award.

His solo work tends toward the fictional magic realism of his 2008 Eisner-Award winning graphic novel "Swallow Me Whole," 2011's coming-of-age anti-war parable "Any Empire" and 2018's ghostly "Come Again." He illustrated Van Jensen's 2019 Little Rock-set graphic novel "Two Dead."

"My kind of weirdo fiction is what I consider my home planet," he says during a telephone interview on a recent visit with family in North Little Rock. "For cartoonists, comics also work as therapy. It's how you work out your problems and how you clarify your life on the page."

HIS OWN DOUBTS

Still, with "Save It for Later," he had to overcome his own doubts about diving headfirst into sometimes deeply personal nonfiction.

"Who cares what I have to say? I don't want to read my memoir comics," he says with a chuckle. "But at a certain point, I have to do this for me."

The new collection began in part with the essay "About Face," about the appropriation of military-style dress among civilians and the embracing of symbols like the skull logo of comic-book vigilante The Punisher.

Originally published at Popula.com in 2018, it stemmed from "all those observations and lingering questions from what turned into 'Any Empire' that were congealing again," he says. "I was watching this very obvious normalization of the iconography and the aesthetic of paramilitary and fascist presence. I realized there was a comic there that I needed to put out."

After a March 2018 meeting with his literary agent in New York, he quickly sketched what he thought would be a thin, raw book of more personal essays.

'BIGGER, SHARED EXPERIENCE'

"As I started working on those and working on 'About Face,' I realized that these were the same project. Each part benefited from the other and had a bigger, shared experience."

In "Good Trouble, Bad Flags," written in 2019, Powell says: "I've never flown the flag ... But within our modern crisis is incontestably the closest to patriotism I've ever felt. I see what we're losing: a basic, imperfect acknowledgement that this society belongs to all of us. This is all so fragile."

In the powerful "Tornado Children," the tension and stress are evident as the pandemic begins and Powell frantically tries to cope and care for his family. Later in the essay he is mourning his friend Lewis, who died July 17, and fending off calls from nosy journalists looking for his comments on the congressman's death.

"Save It for Later" closes with "Wingnut," and shows Powell protesting alone on the streets.

"I did that probably 10-12 times," he says. "You can get so worked up and upset about what you think is your inability in a moment to do anything, or you can stop what you're doin' ... [here Powell, who has a great sense of humor, briefly busts into a line from Digital Underground's "Humpty Dance"] and figure out something that will satisfy that need to speak up and speak out. I may look bonkers, but I'm going to walk around downtown with a very clear sign for an hour and interact with people. Then I go back home and finish my day. It really does something."