Brian Mitchell's second-grade teacher set him straight: No Black man ever had been the lieutenant governor of Louisiana — and he was wrong for saying his ancestor, Oscar Dunn, had been just that.

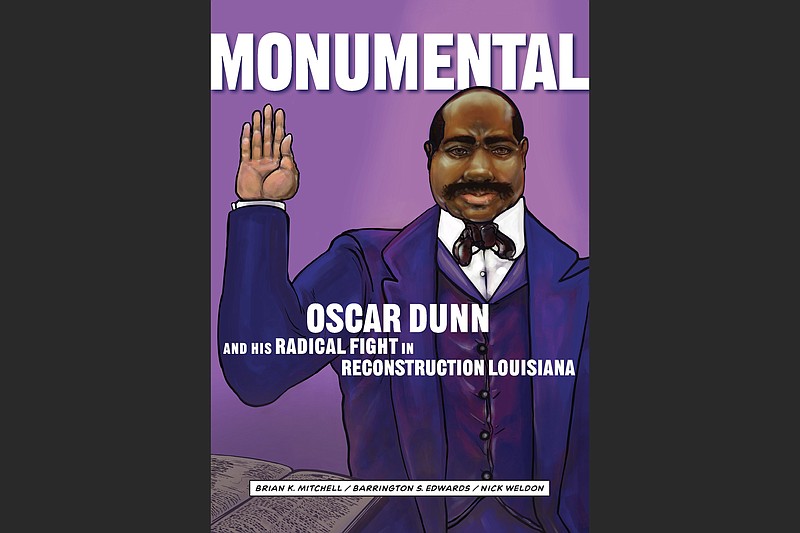

The class made fun, and "I still feel the sting," Mitchell writes 45 years later in the introduction to his new biography, "Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana" (Historic New Orleans Collection).

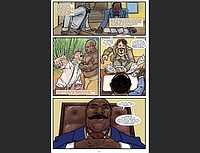

It reads like a comic book story of panels and pictures, and the first page shows the scolded 8-year-old Brian at his school desk thinking, "How could she not know?"

He knew for sure, because his great-grandmother said so. His "grandmaw" kept chickens in her backyard in New Orleans and a scrapbook of family memorabilia, and she told him Dunn was a "big deal."

Oscar James Dunn: He could plaster walls, this big guy, and play the guitar, and he was elected lieutenant governor of Louisiana in 1868 — the nation's first Black lieutenant governor.

Grandmaw said never to forget who Dunn was, and young Brian never did. He grew up to become the go-to guy among historians for his knowledge of Dunn and Dunn's achievements — the subject of his doctoral thesis. Mitchell is assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

He wanted even more people to know about Dunn, who was his great-great-grand — call it distant cousin, Mitchell says, the exact genealogy being nowhere near as interesting as the story he uncovered.

"I could have focused strictly on an academic book," he says. Instead, "I took a very different approach — something unique in Reconstruction history," so one-off that he went with a new name for it: "graphic history."

Like a comic book, that is, but backed with all the same research that would have gone into a scholarly tome of gray type. Notes, sources, acknowledgements — even a glossary of terms that came out of Reconstruction, including carpetbagger, Jim Crow and scalawag. (As in, "That man's no true Southerner; he's a scalawag.")

Dunn was a leading figure of the Reconstruction era, those 12 years after the Civil War when the broken nation faced what early-day Black historian W.E.B. DuBois called "the price of the disaster of slavery."

It was a time of hard questions, some never answered: How to fit the rebellious Confederate states back into the Union? How to define the rights of freed slaves? How to turn a slave economy to the benefit of the workers? How to ensure equality for all? What to do with a nation unwilling to make such changes?

Dunn suited his times with blunt options, plainly spoken. He said government should "derive its just power from the expressed consent of all governed" — and said it with the sort of heavy build that commands attention.

But the best way to get a picture of him? Maybe a book of pictures.

Boston artist Barrington S. Edwards supplies the illustrations that show Dunn's life and times in 180 pages of bright-as-Mardi-Gras color, based on photos and drawings from the period.

"He and I went through the manuscript sentence by sentence," Mitchell says. "We created a database," building on the doctoral paper that some of Mitchell's advisers had discouraged him from trying to write in the first place. There wouldn't be enough about Dunn for him to find out, they said.

One visual source is a black-and-white wood engraving from a publication called Every Saturday, from 1871. It shows Dunn apparently in front of his two-story frame house with a picket fence, the zigzag kind where each slat comes to a point. It shows what he wore — a flat cap in contrast with dressy shoes — and how he stood with his thumbs tucked in the waist of his trousers, overlooking a placid scene that turns out to be the aftermath of a flood.

The most telling thing might be the old engraving's caption: "Lieutenant Governor Dunn prepared for the worst."

Born a slave, he was freed and sent to school by his stepfather, a free man of color. The experience made him a lifelong advocate of free education for all and equal rights for all. He knocked heads with the state's white Gov. Henry Clay Warmoth over civil rights, and Warmoth had him jailed.

He saw war and riots, and knew love, and what kind of New Orleans story would it be without a voodoo spell? — and all this building to a murder mystery.

Mitchell grew up reading X-Men, The Avengers, The Fantastic Four. He knew history, but he also knew, when he saw one, a comic-book story.

Photo Gallery

"Monumental" sample pages

A few sample pages of the comic biography "Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana," courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

DRAWN TO HISTORY

"Monumental" is endorsed as "deeply researched" by Pulitzer Prize-winner Eric Foner; and for depicting a "turbulent time and a brave leader" by National Humanities Medal winner Edward L. Ayers.

"I was always fascinated with history," says Mitchell, who intended for "Monumental" to be a way to share that feeling ... with young readers, especially.

Comic-book readers need look no further than Dunn to find a hero as clean-living as any caped crusader — a figure of justice who, according to Mitchell's research, stood above devil-drink and gambling vices.

The book shows a scene in which Dunn rejects a $10,000 bribe to sign a railroad bill, snubbing around $200,000 in today's money. He not only rejects it, he stiff-arms it while declaring, "Sir, my conscience is not for sale." (Note: the sentence ends with a period, not a comic-book !!!. Historians don't write !!!.)

Published by The Historic New Orleans Collection, the book joins a list of previously published titles in the collection including "New Orleans: The Founding Era"; "A Fine Body of Men: The Orleans Light Horse, Louisiana Cavalry, 1861-1865"; and "Afro-Creole Poetry in French from Louisiana's Radical Civil War-Era Newspapers."

Editor Nick Weldon explains why the publisher decided to give Mitchell's idea of comics a try.

"There have been a lot of great examples of graphic history books lately," Weldon says, citing the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis' "March" series. "We liked the idea of creating something that could appeal to a wide range of readers, and not just the traditional academic set."

Comics are full of doubtful amazements, but it does seem that "Monumental" is one-of-a-kind in being based on a 300-page thesis.

"We hope so," Weldon says. "We tried to do something relatively new, creating this hybrid between a graphic novel and a more traditional scholarly book." It saves "the denser stuff for the back of the book" that reads like a school text with maps and photos.

"If you like the nitty-gritty details and expanded commentary, you have a wealth of material," Weldon says. "The end-notes correspond to the illustrated pages, so you can dive deeper and dissect every scene depicted in the book, which I think is pretty unique to this book."

Mitchell hopes it won't stay unique, but will lead to a series he has in mind of similar books about other little-known figures from the past.

"If it has educational value," he says, "then yes."

DOWN TO THE LAST LINE

Oscar Dunn's story ends like a comics cliff-hanger with his death at age 45, in 1871, just when things were on a roll. As a comics writer would say it: !!!???

Unsolved to this day is the lingering suspicion of murder surrounding his death, which came as a sudden convenience to certain parties who were glad to see him gone. Rumor had it Dunn was poisoned, but his family denied the autopsy that might have detected arsenic. Officially, he died of natural causes. Really?

In the storm of Reconstruction politics, "many people had very good reasons to poison him," historian Mitchell says. But who knows?

And this: If he hadn't died, he might have become governor of Louisiana, the nation's first Black governor. History lacks the answer to what more he might have done in that higher office.

Better yet, this: In 1869, Dunn went to see President U.S. Grant in Washington, and this oddly secretive meeting was no small matter — him being the first Black public official to be received at the White House.

Dunn seemed a possible choice, maybe even likely to be Grant's vice-presidential running mate in 1872, the election that cinched Grant's second term.

Take it all the way, then, and roll out the carpet for Grant's successor, President Dunn, the first Black president — more than a century ahead of Barack Obama.

People like to talk about "what if," Mitchell says. Some writers "what if" their way into alternate histories, speculating how this or that different outcome might have changed everything. But he doesn't.

Historians "don't talk about 'what if,'" he says. "We talk about what happened."

"Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana" ($19.95) is available from The Historic New Orleans Collection in New Orleans at hnoc.org, and other book stores and online booksellers.