A former Arkansas State Police investigator and lieutenant with the Greene County sheriff's office was sentenced to two years in prison and fined $15,200 Wednesday after pleading guilty late last year to stealing more than $30,000 in government funds when FBI agents set him up in a sting operation in late 2019.

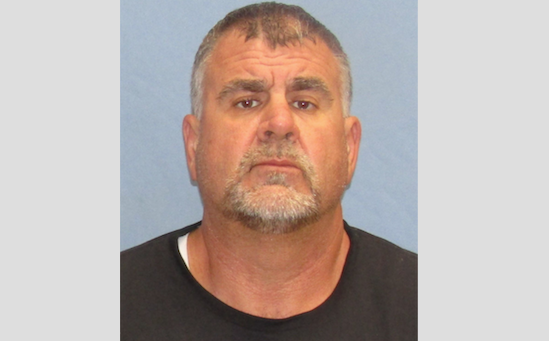

Allen Scott Pillow, 56, was arrested Nov. 5, 2019, after the sting operation during which Pillow pocketed $30,400 in cash that he believed was part of $76,000 in illegal drug proceeds he had recovered from a planted rental vehicle. The money was recovered the next day after a search of Pillow and his home. He pleaded guilty in December to one count of theft of government property before U.S. District Judge Lee P. Rudofsky.

According to court documents, the sting operation was prompted by the discovery in September 2019 by officials at Arkansas State Police Company F that $13,570 was missing from three separate case files. The next month, the FBI sting was conducted and Pillow was arrested.

The 24-month sentence was double the top end of the United States Sentencing Guideline range of 6 to 12 months imprisonment but was far less than the maximum statutory penalty of 10 years that the U.S. attorney's office was seeking. Assistant U.S. Attorney Erin Siobhan O'Leary argued that incidents listed in a motion for an upward variance that were alleged to have occurred toward the end of Pillow's 28-year law enforcement career showed a pattern of abuse that justified the maximum sentence.

But Pillow's attorney, William Jennings Stanley of Jonesboro, after picking apart the substance of the allegations, insisted that because insufficient evidence of those allegations existed for criminal charges to be filed in circuit court, it should not influence Rudofsky's sentencing calculations.

For the most part, Rudofsky agreed, saying there was no preponderance of evidence to support those allegations but he said Pillow's position of trust and authority required a more substantial sentence than that recommended by the guidelines.

"When you look at what would be a just punishment for an officer taking seized money," Stanley said, in arguing for a guideline sentence, "prosecuting him and making him a felon is a pretty big punishment for someone who spent 28 years in law enforcement. Something within the guideline range is pretty significant punishment."

O'Leary argued that although the guideline sentence range purported to account for people in positions of public trust, she said the authority wielded by people in positions of public trust would vary widely and a sentence appropriate for a corrupt accountant would not be sufficient for a corrupt police officer. To serve the purpose of protecting the public from future behavior, to send a message of the seriousness of the crime, and to deter others from acting in a similar fashion, she said, required a more stringent sentence.

When Rudofsky asked what sentence she would consider appropriate for only the indicted offense and disregarding the offenses that had been alleged but never charged, O'Leary said five years would be acceptable.

"I do think it has to be very, very clear both to Mr. Pillow and to everybody looking in how serious this crime is and how much it cannot happen, and shouldn't happen," Rudofsky said. "Where I think I disagree with you is that that means 10 years is necessary and, quite frankly, I'm not even sure five years is necessary... Why wouldn't four years, or three years, or two years, or one year serve that purpose?"

O'Leary conceded Stanley's point that for a person -- especially a police officer -- with no criminal record, simply prosecuting them and making them a felon did constitute a grave punishment but said it was still not sufficient to address all the ramifications of a person in Pillow's position of authority abusing that authority.

"The public has to have trust in law enforcement and a person in his shoes is part of that system of justice," O'Leary said. "The system will not work when people do not do what they are supposed to do when no one else is watching."

She said the actions of Pillow and others like him worked to undermine public confidence in the justice system and wound up making the job of law enforcement even more difficult and more dangerous.

"His actions caused unknown damage, especially at a time that we can all appreciate is especially tenuous in our nation," O'Leary said.

"This is not an easy case," Rudofsky said, gravely, as he announced Pillow's sentence. "It is critically important to society that not only are police officers honest and fair but that they are also perceived to be honest and fair and law-abiding and honest brokers. We give law enforcement an enormous amount of authority and the only way that people are going to accept the authority we give law enforcement... is to make sure law enforcement lives up to those standards."

Rudofsky gave Pillow 46 days to get his affairs in order before reporting to prison, ordering him to report on June 7 by 2 p.m.