VATICAN CITY -- On the morning of Sept. 29, 1978, the Vatican issued a short and stunning bulletin, announcing that Pope John Paul I was dead of a heart attack, his body discovered in bed by a priest who served as his personal secretary.

That was the first version of what had happened, at least.

Within days, rumors of foul play were spreading. Cardinals in the Roman Curia pressed for clarifications. When an Italian wire service revealed that the Vatican had misidentified the person who'd found the corpse, the sense of mystery only grew: What might explain how a pope, at age 65, could die after just 33 days on the job?

Four decades later, John Paul I is on the trajectory toward sainthood. The Vatican has announced he will be beatified, after a first miracle -- the healing of a critically ill 11-year-old girl in Buenos Aires in 2011 -- has been attributed to his intervention.

But to the extent he is remembered, it is primarily for the suspicions about his death.

Over the years, a small number of people have plunged into the case, each taking drastically different approaches -- and only some hewing to the facts. John Paul I's legacy has come to be defined not only by mystery and conspiracy, but by competing attempts to set the record straight.

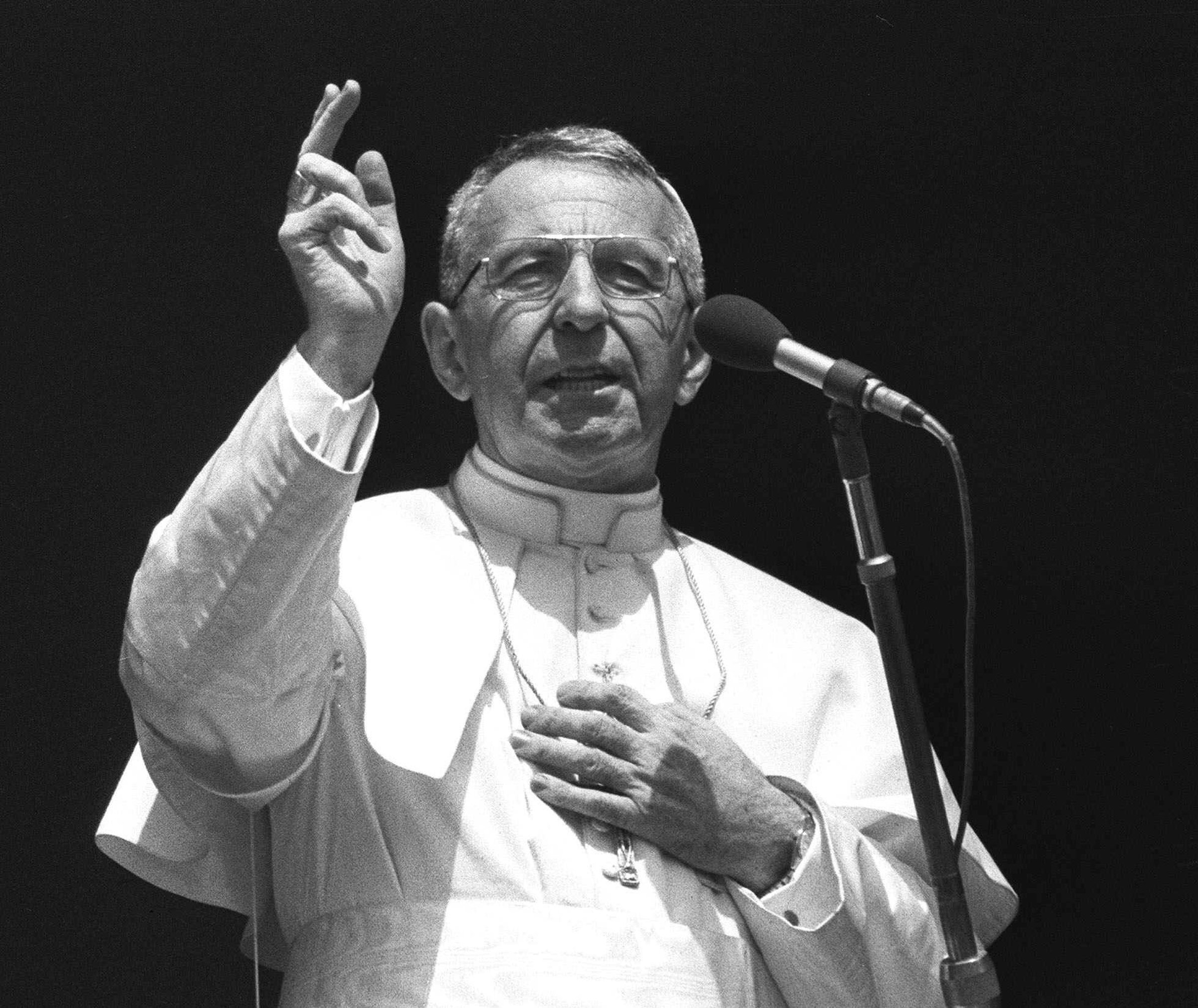

What all accounts agree on is that John Paul I was a pope different from so many others. He came from a poor family in Italy's mountainous backwoods. He had never wanted to be anything more than a country priest. He was chosen quickly in the conclave, which lasted just 26 hours, and after his selection, he made a good public impression. He did away with some of the pomp of the office. He used simple language.

"Never could I have imagined ... ," John Paul I said on his first day as pope.

Then, barely a month later, his pontificate was over -- the shortest reign since the early 1600s -- and the Catholic world was left to make sense of the inexplicability.

Why had the Vatican misreported who found him? Why had there been a seeming rush to embalm the body, without an autopsy? The questions swirled for years before British crime writer David Yallop published a book about the case and concluded the church was surely covering up a murder. His theory was that John Paul I had been poisoned, struck down by the Vatican deep state just before he could reveal corruption at its highest levels.

Yallop's 1984 book, "In God's Name," offered scant sourcing or evidence. But it gained popular power by piggybacking on a real Vatican banking scandal -- one that involved a masonic lodge and an Italian banker who'd died under mysterious circumstances. In Yallop's telling, John Paul I's death was a part of that story, because behind the scenes, he had trained his eye on the financial corruption, putting the Curia on edge. Yallop named six people who stood to gain if the pope were suddenly removed. One was Cardinal Paul Marcinkus, a burly American who headed the Vatican Bank.

In the book's most memorable scene, Yallop described how a dazed Marcinkus had been spotted inside the Vatican walls at an unusually early hour on the morning John Paul I's body was discovered.

"Marcinkus had the motive and the opportunity," Yallop wrote.

The Vatican called the claims "absurd." But the book became, in effect, the second account of how John Paul I died, after the Vatican's own.

"In God's Name" sold 6 million copies.

BOLD COUNTER STRIKE

By the standards of a church that rarely tries to clarify controversies -- and indeed abides a certain level of mystery -- its next step amounted to a bold counter strike. In 1987, Archbishop John Foley, an official in the Vatican communications office, got in touch with yet another British journalist and author, John Cornwell, offering him the mission of dispelling the falsehoods. Cornwell, a lapsed Catholic and former seminarian, headed to Rome and started knocking on the doors of the key players. After being invited to a private Mass with John Paul II -- a de facto blessing for the project -- many of those doors started to swing open.

It didn't take him long to find central flaws in the conspiracy theory.

The Vatican had falsely indicated who found the body, it turned out, simply out of shame to admit that a woman -- a nun working in the papal apartments -- was the one who had entered the papal bedroom. What's more, John Paul I did not appear to have a secret agenda, nor any appetite for digging into the church's finances. And the circumstantial evidence used to connect Marcinkus to a murder plot could be easily dismissed: The cardinal was an early riser, and it was routine for him to be in the Vatican by 6:30 a.m.

Cornwell, in that sense, served exactly the role the Vatican had hoped for. But he was anything but an institutional mouthpiece -- and he used his long talks with gossipy prelates to create a new theory of John Paul I's death.

According to the narrative Cornwell developed, John Paul I's brief pontificate had been careening toward disaster -- and many in the Vatican could see it. The Curia mocked the new pope as unsophisticated, childish, with a "Reader's Digest-mentality." And he was breaking under the pressure of his role. Leaning heavily on interviews with John Paul I's priest-secretaries, Cornwell described the pope as asking daily, "Why did they choose me?" John Paul I believed his selection had been a grave mistake.

"He was not going to be a great pope," Cornwell, now 81, said from London.

CHEST PAINS

Cornwell's book included an anecdote, relayed by one of John Paul I's secretaries, John Magee, of one day when the pope let slip a clutch of documents while walking on a roof-deck garden. The pages fluttered downward, scattering across several roofs, and the pope was in despair, saying, "Oh my God, oh my God." Magee suggested John Paul I go lie down. The Vatican fire brigade eventually managed to collect every piece of paper. But all the while, the pope was curled up in a fetal position on his bed, according to Magee, broken by even modest adversity.

Cornwell had no doubt that John Paul I's death was natural -- either a heart attack or an embolism. The pope had a track record of circulatory problems; his lower legs were swollen. He'd complained of chest pain hours before his death.

But the book, in its most controversial part, claimed that John Paul I's death was connected to his fractured mental state. One of the pope's nieces, Lina Petri, was quoted saying that perhaps the stressed pontiff had neglected to take anticoagulant medication. (Petri, in an interview with The Washington Post, said she "could not possibly know" whether her uncle had or hadn't taken medication.)

The book homed in on the detail that the pope, after registering pain, had waved off his staff from calling a doctor.

In this third version of the story -- more tragic than any conspiracy, Cornwell wrote -- John Paul I was a pope who wanted to die. "It took only his refusal to see a doctor and the heedlessness of others to ensure the end he so devoutly wished for," Cornwell wrote.

MORE METHODICAL

Stefania Falasca, 58, makes clear that her version of events -- the most recent -- resulted from a process more methodical than any earlier undertaking. She had access to a trove of never-before-seen documents. She read confidential doctors' reports and notes about the pope's clinical history. She happened upon this privilege by virtue of her role: She is the vice postulator for John Paul I's sainthood.

A postulator has a difficult line to straddle, charged with promoting a candidate's reasons for sainthood, while also with helping to draft a full biography that might bring to light factors that work against the cause. Falasca's research has helped fill five massive volumes used by the Vatican to analyze nearly every facet of his life and death.

She says her goal is "safeguarding" the realities of John Paul I's life. She can scarcely hide her contempt for the narratives that came before, calling them "noir literature," or tabloid trash, and burying her head in her hands when asked to respond to past theories, including those raised by Cornwell.

"This is the longest-running fake news of the 20th century," said Falasca, sitting in an office several blocks from St. Peter's Square.

Falasca's opinion is shared by the Vatican, whose official news arm recently said her research, summarized in a 2017 book published in Italian, "definitively" closed the case. Falasca presents John Paul I's death as an unanticipated, unpreventable tragedy.

NO HEALTH PROBLEMS

The documents she reviewed indicate that doctors detected no pressing health problems in routine medical checkups during John Paul I's month as pope. To the extent there were warning signs, they came from his medical history: Several people in his family had had sudden deaths, and three years earlier, he had been hospitalized with a blood clot in his eye.

One papal doctor believed heart attack was the likeliest cause of death.

Another doctor who'd previously treated the pope said there was "no clinical doubt" that the cause was circulatory, linked to the same issues that manifested in his eye.

Falasca, who is also a journalist for Avvenire, a church-affiliated Italian newspaper, quotes the conflicting opinions and doesn't try to weigh which was likelier.

But in her book, she implicitly takes aim at past accounts. She lambastes the priest-secretaries -- key sources for Cornwell -- highlighting some of their contradictory statements, calling them unreliable, perhaps on guard for their own reputations.

She notes that a "small circle" of priests and lay people didn't think he was up to the task while leading the ecclesiastical territory of Venice, his prior job. But she also quotes cardinals and a nun in the papal household, testifying to his competence in his short time as pope. He was moving ahead "resolutely" with his tasks, promoting dialogue and peace, up to the point of his death.

Had he lived longer, he could have been a historic pope, Falasca says, "but his death ended up absorbing his whole life story."

TOO OLD TO TALK

Many of the Vatican insiders who witnessed John Paul I's pontificate are dead. Others are too old or wary to talk. At such a remove, some crucial aspects are up for interpretation.

Take John Paul I's attitude toward death. Cornwell says he correctly framed the pope's despondency. He talked to the pope's priest-secretaries at length. Both provided him with similar accounts of a pope who talked readily of death.

"He did not want to stay in the world," one of the pope's secretaries, Diego Lorenzi, told Cornwell.

But in the pope's hometown of Canale d'Agordo, Italy, at the base of the Dolomites, some people interpret the pontiff's perspective differently. They say John Paul I, in talking about death as pope, was doing what he'd done for years: trying to make peace with his mortality.

He'd grown up in an impoverished region where men often didn't reach the age of 60. Infant deaths were common. One of his younger brothers died as a baby, as did three older brothers -- all named Albino. The boy who would become pope was given the same name as those deceased brothers, and barely survived his first days, born with an umbilical cord wrapped around his neck.

In one of his public events as pontiff, John Paul I cited a memory of his mother saying, "I had to take you from one doctor to another and watch over you whole nights."

Today, though, only a few people are even trying to weigh the various stories. Falasca's book was published at a time when popular interest in the case had waned, and Cornwell says his book "didn't make a dent" in public perception.

"Let's face it," Cornwell said. "It's a much better story to say that he was murdered."

In Canale d'Agordo, at a museum filled with tokens from John Paul I's life, most among the trickle of visiting pilgrims believe he died of nefarious means. Over the years, the idea of a murdered pope sank into popular culture, and even featured in the plot of "The Godfather: Part III."

"It's an unshakable myth," said Loris Serafini, the museum's director. "They say he was a pure man up against bad people."

The museum has only a small section dedicated to the pontiff's death. A sign on the wall distills what likely happened into a few sentences -- that John Paul I's body was found by a nun, and that the cause of death was likelier a pulmonary embolism than a heart attack. But in the museum's library, every competing version of what happened is there on the shelf.

Serafini said interest in the pope's death could boom anew if he is canonized, and there will likely be more books.

"It's not over," he said.