Social justice is more than a footnote in the Torah. It's a central theme, Little Rock Rabbi Barry Block maintains.

The Holiness Code in Leviticus requires more than sacrifices and Sabbath observance; it addresses fair labor practices, care for the aged and aid for the poor, Block observes in the introduction to "The Social Justice Torah Commentary."

"The message is clear: Israel serves God no less by pursuing social justice than through proper worship," he adds.

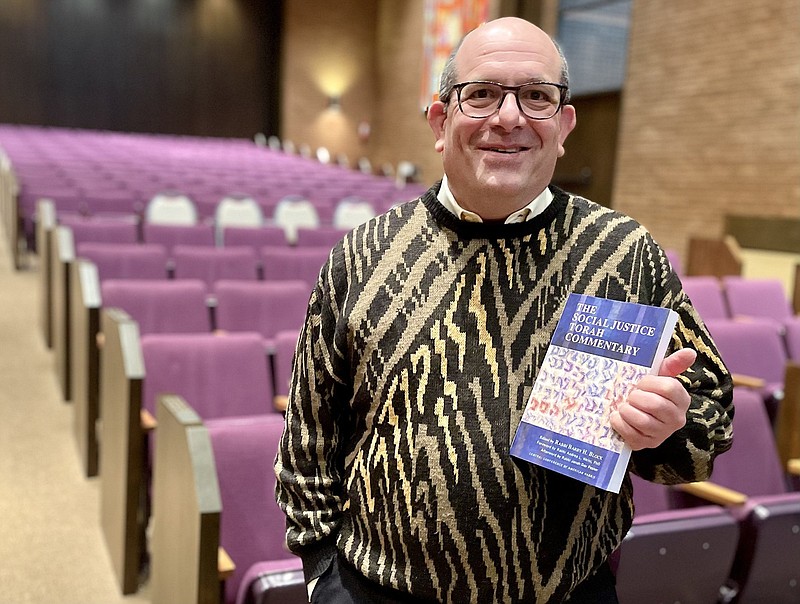

The new Torah commentary, which Block edited, was recently published by the Central Conference of American Rabbis, which describes itself as "the oldest and largest rabbinic organization in North America."

Block is the rabbi at Congregation B'nai Israel, which he has led since 2013.

In Hebrew, Torah means teaching, instruction or law. The first five books of the Hebrew Bible are also referred to as the Torah.

Following longstanding practice, the commentary divides these books into 54 passages -- one for each full week in a Jewish leap year. The commentary on each parashah (from the Hebrew for "portion") addresses a social justice topic, ranging from voting rights and slavery reparations to reproductive choice and mass incarceration.

Some templegoers would prefer to steer clear of hot-button topics.

"People say, 'Rabbi, we want you to teach Torah, not politics. We want you to give sermons about Torah, not politics.' As if those were different things or entirely separate things," Block said during a book launch event co-sponsored by the Central Conference of American Rabbis and the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism.

But the Torah contains God's commands for "how to organize a society, how people must live in community with one another, how we take care of the most vulnerable among us and those who might lack a voice if we don't amplify their voices," Block said.

The Torah's teachings, Block maintains, remain relevant today, for those who seek to build a more just, peaceful and compassionate society.

Rabbi Hara Person, chief executive of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, agrees.

"As Jews, we believe that it is our job to make the world a better place and a book like this that brings together Torah and social justice helps create a road map for us," she said during the book launch.

Block has done "a magnificent job" of bringing together a wide variety of rabbis to write the chapters, Person said.

The finished commentary is "an incredible resource," she said.

"This book connects the theoretical to the quotidian and helps us find our way to the highest aspirations of Jewish values," she added.

Rabbi Jonah Pesner, director of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, called Block a "remarkable editor."

"I believe that this commentary, this Torah commentary, is one of the most important publications of this generation," he said.

By distilling one social justice theme from each of the portions, the commentary provides weekly insight for rabbis and others.

The scriptures, inscribed on scrolls, are revered and read.

"Jews in synagogue life read the Torah, the Five Books of Moses, in an annual cycle every year, and then on a holiday we call Simchat Torah, in the fall, we roll it back and start over on the same night. We always teach and believe that there's always something new to be drawn out of the old text," Block said.

Complete all 54 portions and you will have read the entire Torah.

"In an Orthodox synagogue, they would read the entire portion aloud on a Shabbat morning. We typically pick some select verses to read, but we always do pick them from that portion for that week," Block said.

In the commentary, Block's portion is Leviticus 19:1-20:27, but his focus is on Leviticus 19:9-10, which states:

"And when ye reap the harvest of your land, thou shalt not wholly reap the corner of thy field, neither shalt thou gather the gleaning of thy harvest. And thou shalt not glean thy vineyard, neither shalt thou gather the fallen fruit of thy vineyard; thou shalt leave them for the poor and for the stranger: I am the LORD your God."

"In ancient Israel," Block writes, "providing for the poor was not optional."

Today, most Jews aren't farmers but they still have a moral obligation to help the poor, he maintains.

"Paying taxes is one way we fulfill this commandment today," he adds.

"When we pay for SNAP, the food stamp program that provides subsistence nutritional assistance, mostly for the working poor, we are leaving the corner of our field," he writes, citing it as one example.

Helping the poor is not optional, he emphasizes.

"It's a mitzvah, a religious obligation binding on every Jew," he writes.

Asked about the passage, Block said, "We are required to set aside a corner of our produce -- in other words, a portion of our income -- to see to the needs of those who don't have those fields, who don't have the advantages that others of us have."

Block said he enjoyed working with dozens of fellow rabbis to create the Commentary.

"Part of what I'm so pleased about in the book is its diversity. Not only the diversity of the authors, but the diversity of the positions [they take]," he said.

Several chapters focus on racial justice.

One of the commentary's chapters focuses on "The 'Original Sin' of Slavery." Another is titled "Lynching: Justice and the Idolatrous Tree."

A third chapter discusses Confederate statues while another raises the possibility of reparations for the descendants of enslaved Black people.

"Jews understand the power of reparations," writes Judith Schindler, rabbi emerita of Temple Beth El in Charlotte, N.C., noting that Germany had paid reparations to some of its victims after World War II.

Before the opening of "The Social Justice Torah Commentary," Block acknowledges the racism and oppression in his own family tree.

As he was completing work on the project, he was forwarded a page from the 1860 Louisiana slave census, "actual proof for me that an ancestor -- in this case, my great-great-great grandmother, Magdalena Seeleman -- was an enslaver," he writes.

Block, who supports reparations, dedicated the book to the memory of the Black woman his forebear once owned.