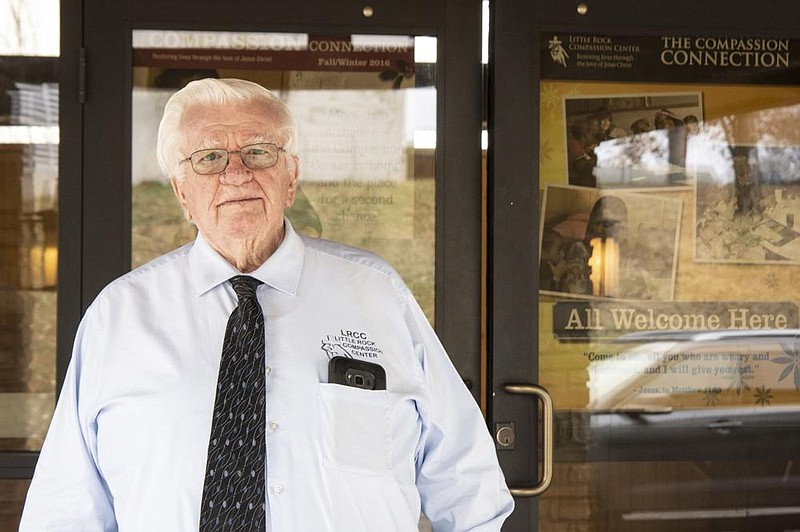

For nearly 80 years, God has had a way of keeping in touch with the Rev. William Holloway, founder and chief executive officer of the sprawling Little Rock Compassion Center that dominates a full city block near the state fairgrounds.

From his hardscrabble upbringing, through addiction and recovery, to his search for meaning through ministry, he says, the Almighty has systematically stepped in to provide gentle and not-so-subtle nudges along the path of life.

Even now, as the center hums about its daily mission of unbinding people from the toxic molecules of their lives that leave them homeless and often hopeless, God's still talking to Holloway, through each of the hundreds of people the ministry serves. Within every person who fills a plate, lands a job or kicks a habit, he sees the Lord beckoning.

"One of the things all my life is, I always took up for the underdog," Holloway says. "If I would see you out here beating up somebody I would have to get involved because I know what it was to get beat up like that. Even today, I'd have to control myself if I come in this room and you're hitting a kid."

"Every day here, I see people just like myself. I see people that got hurt and usually got hurt for no reason at all. So, I have a habit of standing up for them."

Few individuals have stood up for the homeless as Holloway has. Every day, his Little Rock ministry reaches hundreds seeking a hot meal, some clean clothes and in some cases, a second or third chance at life. His flock reads like a social services directory -- homeless, addicted, illiterate, abused, mentally ill, hungry -- as well as many who are just going through a rough patch brought on by covid-19.

"With this pandemic it's really hard to say how many we serve or don't serve," he says. "Today we could have 200-250 here and get up tomorrow and there'll be 75 or 100. There's no reason why; a lot of it is weather-related or first-of-the-month-check-related economics. A lot of these people get checks and it's not really enough for them to live on. A lot of them just kind of fall through the cracks of our society."

"We're also seeing people now coming in here who have lost a job or they've been cut from a 40-hour-a-week job down to 20 hours a week. I see a lot of families now moving around because they lost their place to live. We're also seeing people who are right on the verge of losing their house altogether because of the fact they're not able to make the payments. More people, families, don't have a home."

Throughout the three buildings of the center -- the 48,000-square-foot main structure, a separate 3,000-square-foot women's center and a new 14,500-square-foot building to come online this year -- Holloway, his wife Rosemary, and a staff of 35 have seen many people make remarkable comebacks. Many others he has just seen, again and again, unable or unwilling to shake off what claws at their back.

"A lot of times these people have not had a nutritious meal for days. They come in here and have probably their first real good meal they've had in a long time," he says. "Some of them, they come from these little towns with 400 to 600 people. They don't have hospitals there, they don't have shelters, they don't have food lines. So, they come into Little Rock, and since we're one of the only emergency shelters left for men, we usually end up with them, one way or the other."

HOMELESS KID

"We had a person come through here a couple days ago from Monroe, La. I asked him how he got here and he said a bus and a taxi cab."

At this, Holloway gives a half-grin, hearing a lot of his younger self in the answer. There was a time when the Illinois native would simply have his fill of a place or a situation, find a conveyance that was rolling and just hop on. It was a pattern that started at an astonishingly early age.

"When I was a kid, I was homeless," he says. "I come from a very abusive family and in some ways very dysfunctional. By the time I got to be probably 9 or 10 years old, I started becoming very rebellious because I had about all the abuse I could handle at the hands of my mother. And my dad was a track star. When he seen my mother coming, he made tracks."

He laughs.

"I really probably didn't know what abuse was. I just knew it hurt. When you go to school with your back all striped up from a leather belt or from a switch and you have to hold your clothes up off of your back to keep it from stinging, I guess one day I got enough. That was it. I just walked off."

Left to his wits, the young Holloway quickly learned the laws of the streets starting with how to steal food to survive. He mastered the art of entering a grocery store with a bogus list as if shopping for his parents, making and eating a sandwich on the sly as he "shopped."

"When you get done eating you head for the door and leave the basket wherever it's at," he says. "Then you knew not to go back there for several days."

Holloway's activities soon put him on authorities' radar and when the heat was on, he'd skip town to let things cool off.

"You live from one hour to the next in that life, because everything changes in that hour," he says. "If you're out here running with a bunch of kids and for one reason or another somebody does something wrong, you scatter. If the law's looking for you, you hop a freight train and ride to Memphis. I had a sister in Memphis so I used to ride and say, 'I'm going down to see my sister.' I had no intentions of going to see my sister, I was going to Memphis to run around. Then I'd go back home, stay two, three, four, five days, whatever I thought was comfortable. Somebody would start bothering me or abusing me I'd just leave again."

Within this cyclical lifestyle, Holloway had little use for institutions and even less use for religion. Booze, though, was a revelation all its own.

"I think I started drinking probably around age 6, 7," he says. "The first time I ever got drunk I was around 6 years old. And when I got drunk, I felt like I was on top of the world. I didn't have any problems. It was just like they were gone. I was free to be me, so I just kept on going."

Alcohol was the octane to Holloway's aggression and the older he got, the more predictable his drink-fight-jail pattern became. A three-year hitch in the U.S. Army kept him fed but did little to temper his binges or his fists, as a general once noted in no uncertain terms.

"He said, 'People like you should be left on a shelf during peace time,'" Holloway remembers. "'You're a dangerous man.'"

His lifestyle finally caught up with him in the form of a judge who laid it on the line: Get hard time or get sober. Holloway chose the latter in what would be a monumental turning point in his life.

"I went through AA and I just happened to luck out that one of the AA groups that I was in was more or less Christian," he says. "I started learning a little about God here and a little about God there. I was about 29 years old then and as I got older, I started going to church over here, church over there, once in a while. It just continued on."

A VOICE FROM GOD

It was at this point, Holloway remembers, God decided to get his attention more directly. Now living in Minnesota, he was in the car one day when he noticed the world around him began to change shape.

"It was like I was in a trance. I said, 'Lord, how can I do Your work when I can't even see to read?'" he says. "I turned the radio on in my car, which I don't listen to. I hate radios, or I did at that time. I turned it on and it was a Christian station and a man got on there and he said, 'I was in prison and I couldn't read when I went to prison, but I got myself a set of Bible tapes. I went over them and over them and over them until I could almost recite the Bible.'"

"It made me stop. Why was my radio on that station and why was that man at the particular time saying that? So, I started going to church full time. Got where I couldn't stay away from church. Every time the church doors was open, I was there."

Having made an impression, God hit Holloway again, this time while attending services. Right in the middle, he saw the walls fall away and caught a clarion glimpse of a life in ministry.

"There was a vision right there taking place with me. I could see it just as clear as it was written on the wall," he says. "When I got up from that service people said, 'What's wrong with you? What's happened to you?' They said, 'You're shining.'"

Inspired, Holloway nonetheless felt he couldn't take on a ministry like what he'd seen alone and so he prayed for the kind of wife described in Proverbs 31. That's all the Almighty needed and he crossed his path with Rosemary, his second wife. A New York native relocated to Paris (Logan County), Rosemary was the recently widowed neighbor and friend to Holloway's mother Ardth, with whom he had reconciled.

Holloway wasn't initially what Rosemary had in mind, and their first date took some wrangling on his part.

"My first husband was an alcoholic and I went through a bad marriage. Both my parents were alcoholics and my mother was abusive. I got a lot of beatings for things I didn't understand," Rosemary says. "I just wasn't interested. Wasn't thinking about dating anybody. And [Ardth] had told me so much about him, all the mischief and stuff he went through."

"Well, it was a few months later he came down to get her ready to take back to Minnesota with him and he asked me to go out with him. It was basically a date, but he preached to me for six hours."

Rosemary's reticence eventually cooled, and she and Holloway married. Joining him in Minnesota, she got an awakening as to the type of ministry the now-reverend (a title he earned online) was engaged in.

"We lived up there about two years and I got to learn a lot about homeless people. Before that, I had never been around them, I was kind of leery of them," she says. "I learned what compassion is about from him. Sympathy is I feel sorry for you, here's a dollar or whatever. But compassion is I know where you've been. I've been there and done that. I know how to pray for you."

The final catalyst for what would become Little Rock Compassion Center was a trip back to Paris for a family Christmas. After listening to the pastor list the things the congregation had done that year for its less fortunate congregants, Holloway leaned over to his wife.

"He says, 'These are things that should be done every day of the year, not just at Christmas,'" Rosemary says. "And it was like God said, 'OK, it's time to move.' It was just that plain."

LET ME SHOW YOU HOW

As great as the need was, getting the ministry off the ground in Little Rock took massive effort. Holloway rented a dilapidated old building on Asher Avenue in which the couple began cooking breakfast for the homeless starting between 4-5 a.m. Then, Holloway would operate his roofing and siding business only to come back and they'd cook supper for the people around 4 p.m. It was a back-breaking schedule.

"She's a hard worker and I'm a hard worker, so we don't cry over spilled milk," Holloway says of those days. He shrugs. "We get up and go to work."

First attracting just three or four people to mealtime, the ministry quickly multiplied and as the numbers grew so did the breadth of problems the people brought with them. The center bought its bigger main building in 2004, creating a beacon for those needing help. Melissa Caulder is among them.

"After 25 years of abuse -- mental, physical -- doing drugs, prostitution, stealing, whatever I could do to get my drugs, my husband and I were dropped off in that parking lot eight years ago," she says. "And the woman that dropped us off said, 'This is where you need to be.'"

The couple arrived unsure of how to untangle the mess that drugs had made of their lives. Though he didn't know they were coming, Holloway was waiting on them.

"I think the Holy Spirit walked me off that parking lot and got me through those doors," Caulder says. "When I talked to pastor, I didn't tell him I had a drug problem. But he knew. He knew I was hard-headed and I was going to do what I was going to do. He said, 'I know where you need to be. You need to be in this program. Let me show you how.'"

Through hard work and the inevitable setbacks, Caulder reclaimed her life and dignity. She now manages the kitchen at the center where daily she sees her former self mirrored in the people she feeds. The constant reminders of her past life fuel her gratitude to the ministry that put her here.

"I was just praising the Lord because my husband and I have so much to be thankful for. We have jobs. I've been working here almost seven years. I've never worked at nothing for seven years," she says. "We have a new car. It's not new, but it's new to us. We have a house and we adopted our grandchildren because their mother did drugs. I'm just so blessed; I'm so blessed because of walking through those doors."

With that, Caulder wipes her eyes, smiles and leaves to continue cooking. Holloway watches her go like a proud father. Not every story turns out like hers, just as not every abused boy turns out like he did. In the end, it only matters that the paths intersected, here, in this place of faith and hope.

"I see my life as an education," he says, gazing out the office door. "I wouldn't be where I'm at today if I hadn't gone through the things that I got to go through. So, I'm not bitter about it.

"Anybody who knows me knows I love the ministry and I love carpentry. Matter of fact, I'm not done building yet."

SELF PORTRAIT

William Holloway

• DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: Oct. 16, 1942, Carlinville, Ill.

• EDUCATION: Self-taught (I like to say Bible-educated)

• FAMILY: My wife, Rosemary, and I married in 1995. I have four biological children and four stepchildren.

• THE BIBLE VERSE THAT'S MY GO-TO WHEN TIMES GET TOUGH IS: "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge, but fools despise wisdom and instruction." (Proverbs 1:7)

• THE MOST IMPORTANT THING TIME, AGE AND EXPERIENCE HAVE TAUGHT ME IS: Compassion for others.

• THREE THINGS I AM NEVER WITHOUT ARE: A Bible, a phone and never forgetting where I came from.

• THE ONE THING I KNOW TO BE ABSOLUTELY TRUE ABOUT ALL PEOPLE IS: They need a shepherd.

• A TALENT OR SKILL THAT I WISH I HAD IS: The ability to fly a bi-plane.

• MY PROUDEST ACCOMPLISHMENT IS: When I see a person turn their life over to Christ, forgetting the past and looking forward to the future.

• THE BEST PIECE OF ADVICE I EVER GOT COMES FROM: Romans 13:8, "Owe no man anything but to love one another."

• THE ONE WORD TO SUM ME UP: Steadfast