There is a perspective distortion that comes with looking backward.

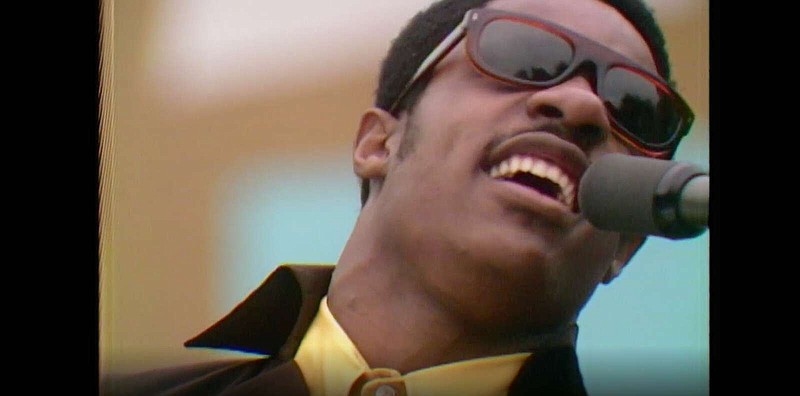

Stevie Wonder was 19 on July 20, 1969, when he walked onstage at the Harlem Cultural Festival, an event that would be lost to legend and rumor were it not for Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson's just-released directorial debut "Summer of Soul (... or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)."

He looks so young, whippet-slim and dangerous in a way you don't expect this avatar of joy to have ever looked. I know better, but still expected him to seem at least a decade older. By the summer of 1969, Stevie Wonder'd already released 10 albums. Berry Gordy had signed him to Tamla Records, a Motown subsidiary, when he was 11 years old. He'd been on the radio, in my ears, nearly my whole life. He'd already amassed enough hit singles to ensure a lifetime of what the songwriters call "mailbox checks."

Whacking furiously at a drum kit during a loose version of the Isley Brothers' "It's Your Thing," Wonder is electric, a kinetic dervish of a performer who was yet to mature into the artist he would become. His 11th album, "My Cherie Amour," would be released a few weeks later. No one has ever matched the five-album run Wonder had from 1972's "Music of My Mind" to 1976's "Songs in the Key of Life," but I didn't expect him to look so much like a kid.

The sequence is the kickoff highlight of Thompson's film (in theaters and on Hulu), and is one of the few moments in this remarkable documentary that's not contexturized by talking heads. And that's all right; it's fine to just watch genius at play.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/711soul]

But I want to think about that moment that would have been lost forever had some 40 hours of 50-year-old video footage not been found languishing in a basement.

Questlove saw that drum solo and knew he had to put it in the film, and there's obviously a lot he had to leave out, but what's fascinating is not that Wonder is performing a cover song in the film — lots of cover songs get performed when artists are trying to reach large live audiences — but it is interesting he's performing that particular cover song.

"It's Your Thing" had reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 earlier in 1969, but had dropped off the charts by July. (Wonder's single, the title track off the next album, was in the Top 10.)

It's also interesting that "It's Your Thing" was widely interpreted as the Isley Brothers' kiss-off to Berry Gordy and Motown Records, which was also Wonder's label. (The lyrics — "it's your thing, do what you wanna do ... I can't tell you who to sock it to" — might support more than one interpretation.)

Either the Isleys had refused to renew their contract with Motown or Motown dropped them. In any case, the Isleys believed Gordy had consigned them, as a gritty funk band, to second-tier status behind more radio-friendly acts like Diana Ross and the Supremes, the Temptations and a newly signed band from Gary, Ind., called The Jackson 5.

Gordy was said to be irritated by the song; he threatened to sue the Isleys, alleging they'd written and recorded it while still under contract to Motown. He claimed it was a Motown song. He had The Jackson 5 perform it in concert, and record a version of it for their second album, 1970's "ABC." (The track didn't wind up on the record, but was finally released in 1995 as part of the "Soulsation!" boxed set.)

An alternate version has the Isleys approaching Gordy with the song, only to have him reject it out of hand as "not a Motown song."

In any case, The Isley Brothers were not popular with Gordy in 1969. So it's interesting Wonder chose to play this particular song at this festival.

One thing that most people who care about such things know is that when Wonder turned 21 in May 1971, Gordy was legally obligated to release about 10 years' worth of royalties the label had held in trust for their juvenile star. And the only way Gordy could keep him signed to Motown Records was by giving him a new deal that not only granted him him full artistic control over his music but his own publishing company, and an unprecedented royalty rate.

'CLASSIC PERIOD'

This set the table for the tsunami of creativity of what's often called Wonder's 1970s "classic period."

Stevie Wonder got to do it his way after he turned 21; he didn't have to answer to Berry Gordy (who, if he'd had it his way, would never have released Marvin Gaye's masterpiece "What's Going On" on the grounds it was political and thus divisive — Gaye had to essentially go on strike to force Gordy to release the song and album) or any other Motown A&R executive.

The lesson is you don't try to curate genius; if you're lucky enough to have a Stevie Wonder or a Marvin Gaye in your stable, you let those horses run.

This context makes Wonder's choice of playing "It's Your Thing" — a song that, to my knowledge, he never recorded — at the festival very curious. It could have been a spontaneous gesture. Wonder had a live spontaneous gesture to thank for his very first hit record, "Fingertips — Part 2," which is really nothing more than an ecstatic harmonica jam tacked onto the end of an instrumental performance ("Fingertips — Part 1").

As 13-year-old Wonder and his band were leaving the stage to make way for the next member of the Motown Revue (Mary Wells) to perform, Wonder suddenly started up again, causing Wells' bass player, who was just plugging in, to excitedly ask, "What key? What key?" as he tried to vamp behind him.

Six years later, Wonder is no less an instinctive performer, a conduit for some larger energy fed by the crowd. Maybe he's not thinking; maybe it's just that "It's Your Thing" has been in the air, something on which he can improvise (as he interpolated "Mary Had a Little Lamb" into that "Fingertips" performance).

Or maybe he's sending Berry Gordy a subtle message.

Take a look at "My Cherie Amour," the album that Wonder was about to release. It's a weird one.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/711isley]

CHANGE OF VOICE

That might be due to the fact that Wonder's voice was that of a teenager throughout the '60s. It was going to change at some point. Up until sometime in 1967, he could present as a stirring soul shouter in the mode of Ray Charles — listen to "Uptight (Everything's Alright)" from November 1965 or "I Was Made to Love Her" from June 1967. But then, well, his voice became unreliable. So there was a hold put on recording Wonder's vocals.

Prior to "My Cherie Amour" (the album), Wonder released "Eivets Rednow" ("Stevie Wonder" spelled backward), an easy-listening instrumental album that showed off his harmonica playing (and scored a minor hit with his cover of "Alfie").

"Eivets Rednow" could be dismissed as a one-off experiment by a bored teenager waiting around to discover his mature voice. But "My Cherie Amour" (the album) signaled some uncertainty, if not deep dissatisfaction, with the way Wonder's career was going. It feels simultaneously rushed and beset by a lack of urgency.

While the basic tracks of the title tune had been sitting around in the vaults since 1966, waiting for Wonder's finishing vocals, it is nevertheless the album's best song, a near-standard. (It was originally titled "Oh, My Marsha," and was written for Wonder's girlfriend while he was at the Michigan School for the Blind in Lansing, Mich.)

But it's also a ballad that might appeal to an older and whiter audience. While Wonder had always recorded ballads, it's worth noting that the rest of the record consists of material that feels like typical Las Vegas lounge-singer fodder.

There's Johnny Mandel's "The Shadow of Your Smile," which had been featured in the movie "The Sandpiper" and had been covered by the likes of Perry Como, Frank Sinatra and the Boston Pops. There's an odd arrangement of "Hello Young Lovers," from the 1951 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical "The King and I." There's The Doors' "Light My Fire."

Even Ron Miller and Bryan Wells' excellent "Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday" — originally written for Motown's blue-eyed-soul chanteuse in residence Chris Clark (a six-foot, platinum blond force of nature best known for co-writing the screenplay to "Lady Sings the Blues") — is a middle-of-the-road track.

It might not be completely fair to blame Gordy for Wonder's penchant for schmaltz — even after he gained complete creative control of his music, he released songs like "I Just Called to Say I Love You," "Ebony and Ivory" and "Sunshine of My Life."

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/711fire]

'ANOTHER SAMMY DAVIS?'

Six weeks before Wonder took the stage at the Harlem Cultural Festival, Melody Maker magazine ran a story with the headline "Will Stevie Wonder Become Another Sammy Davis?"

The implications were not kind; Sammy Davis Jr. was largely seen, by Black audiences at least, as a modern minstrel-show performer who curried favor from white audiences by perpetuating stereotypes (tap dancing, for example).

The analysis, fair or not (and Davis' career and reputation are in need of re-evaluation), was that Davis had forfeited his chance to become a first-rate authentic artist by somehow kowtowing to popular (white) taste.

This is a problem faced by every Black artist who attains a certain level of popular success in this country; Louis Armstrong and Wonder's fellow performer at the Harlem Cultural Festival, B.B. King, had to deal with these sort of insinuations. For our purposes, it's important to know that 19-year-old Stevie Wonder, when he stepped onstage at the festival on July 20, 1969, was aware of this talk.

No doubt he knew about the Melody Maker story. Never has genius been truly oblivious to its doubters.

And so Stevie Wonder covered "It's Your Thing," as a thumb in the eye of Berry Gordy. Or maybe a warning.

Or maybe it was just a tune that lodged in his head.

But consider that in 1971, when he was still 20 years old, a month before he signed his unprecedented game-changing deal with Gordy, Wonder released an album called "Where I'm Coming From." He wrote all the songs on it in collaboration with his then-wife Syreeta Wright.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/711talk]

WHERE HE (WAS) COMING FROM

As Stevie Wonder albums go, it's probably a B-minus effort, with the highlight coming at the end of side one with "If You Really Love Me." It also includes the ballad "Never Dreamed You'd Leave in Summer." The rest of it, is, to be kind, highly anticipatory of the golden age soon to come.

Wonder puts his social consciousness on display, but the lyrics are dull and a little too on point, with the nadir coming with "I Wanna Talk to You," a sub-Randy Newman dialogue between two old men, one presumably Black and the other white, both parts sung by Wonder.

"Where I'm Coming From" is often unfavorably compared to Gaye's "What's Going On," which came out about the same time. But it's a very effortful album. It's the sound of a young Stevie Wonder trying very hard to do better; to, in Bruce Cockburn's memorable phrase, "kick at the darkness 'til it bleeds daylight."

He wouldn't break through with "Where I'm Coming From," but his time was coming.

Watching "Summer of Soul" and knowing all this is humbling. It's like having an angel's-eye view on the world. We look down and know all the destinies; we suddenly have access to a would-have-been forgotten world. It's amazing.

And it makes you wonder how many worlds we have lost.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com | blooddirtangels.com