The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences has been awarded a multimillion-dollar grant from the National Institutes of Health for a phase 1 cancer clinical trial that could increase the effectiveness of a chemotherapy drug commonly used to treat breast cancer and lymphoma, among others.

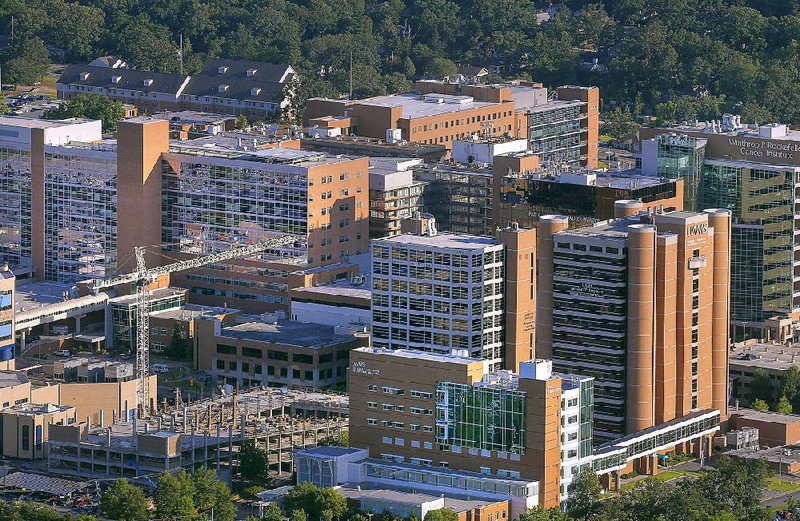

The study, called the Phoenix Trial, also will help the UAMS Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute vie for a National Cancer Institute, or NCI, designation, which is awarded to cancer centers "around the country that meet rigorous standards for transdisciplinary, state-of-the-art research focused on developing new and better approaches to preventing, diagnosing and treating cancer," according to the NIH.

There are 71 NCI-designated cancer centers in the United States, mostly affiliated with university medical centers, like UAMS, where the Rockefeller Cancer Institute recently opened a phase 1 cancer clinical trial unit.

This is the first phase 1 cancer trial at the center.

Such trials are important as they are often the first time drugs are tested in humans, paving the way for phase 2/3 trials and eventual regulatory approval.

The drugs in the Phoenix Trial already received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

Dr. Michael Birrer, Rockefeller Cancer Institute director and vice chancellor, said he also believes the NIH-backed $3.5 million trial will help attract more industry to Arkansas, in particular pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

"This is a huge step for us, and it is a huge step for the state of Arkansas," Birrer said. "It is a real opportunity to leverage this both for the health of our patients and also from an economic standpoint."

The trial centers on two drugs, dexrazoxane and doxorubicin, used in conjunction chemotherapy.

Dexrazoxane is administered alongside doxorubicin to mitigate potential heart damage caused by doxorubicin, the cancer-fighting drug.

The issue has been that dexrazoxane decreases doxorubicin's effectiveness at killing cancer cells even though the drug helps prevent long-term heart damage, not uncommon with chemotherapy.

Over the past decade, the field of cardio-oncology has emerged to study cardiovascular diseases that occur as a side effect of chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

The field has become more prominent as patients with cancer are living longer, and more frequently experience the negative side effects of chemotherapy on their hearts as they age, Birrer said.

"Frankly, our patients are living longer, and when they are living longer, they get more of the downstream toxicity effects, including long-term damage to the heart," Birrer said. "So this is really important."

Because of the potential heart damage, the two drugs are not as commonly used, Birrer said.

Doctors "are afraid that [dexrazoxane] not only will protect the heart but it will interfere with the drug killing the tumor," Birrer said.

This trial could change that.

UAMS researcher Dr. Hui-Ming Chang, who is leading the study, says she discovered in experiments with mice that when dexrazoxane was administered eight hours ahead of doxorubicin, it completely protects the heart without interfering with doxorubicin's ability to kill cancer cells.

Chang says her findings are a major breakthrough as heart damage caused by doxorubicin, the cancer-fighting drug, is "not reversible."

"I like this project because it is about prevention," Chang said. "The best way is to prevent it before any [heart] damage happens."

Which is almost immediately with doxorubicin, she said.

Chang tells the story of one of her students whose father had childhood leukemia that was treated with doxorubicin, only to develop major heart problems at age 50 that required an implantable defibrillator.

"For this particular case, it was amazing for me to hear this story," Chang said. "This is early for the typical population requiring this intervention."

"That is the delayed effect," Chang said. "You do hear cases like this. It may not be immediate. For some people [heart damage] may be earlier, for some it will be later."

Chang said that tests on mice show that administering dexrazoxane eight hours in advance of the other drug degrades a protein that would allow doxorubicin to damage the heart.

"This protein remains degraded long enough for dexrazoxane to leave the system so that it does not inhibit doxorubicin's beneficial effects," she said.

The study is recruiting 25 healthy women, ages 18-65.

If phase 1 is successful, a phase 2 trial would focus on female patients with non-metastatic breast cancer, she said, because of the prevalence of breast cancer among women and the high survival rate of the disease.

"If the data is as we have expected, then this is indeed going to be a wonderful thing for patients," Chang said. "But we have to wait and do things one step at a time to get the necessary data."

Women interested in volunteering for the study can email Phoenix1@uams.edu. Compensation is available.