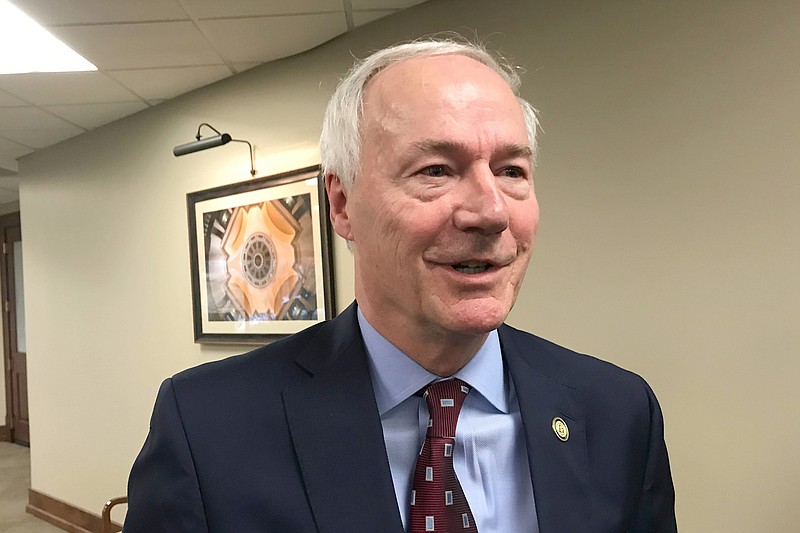

WASHINGTON -- Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson urged the Senate Judiciary Committee on Tuesday to eliminate sentencing disparities in cocaine-related cases, saying crack and powder forms of the substance are equivalent.

Hutchinson, a former U.S. attorney and head of the Drug Enforcement Administration, told lawmakers that the double standard is harmful and has done "disproportionate harm to communities of color."

"The sentencing disparity is unfair. Just as importantly, it is perceived as unfair and undermines confidence in our criminal justice system," he said. "All those in law enforcement understand how critical a sense of fairness is to achieve cooperation, respect, and to reinforce the rule of law."

Testifying at a hearing titled "Examining Federal Sentencing for Crack and Powder Cocaine," Hutchinson appeared on a panel with the acting director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Regina LaBelle.

The acting director told lawmakers that the Biden administration "strongly supports" legislative efforts to fix the disparity.

Known as the Eliminating a Quantifiably Unjust Application of the Law -- or EQUAL -- Act, the bipartisan legislation is sponsored by U.S. Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J. It's co-sponsored by the Judiciary Committee's chairman, U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., as well as Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio.

A version of the bipartisan bill also has been introduced in the House.

Asked about the difference between powder and crack cocaine, LaBelle said, "They're similar, and they have similar effects on the brain."

"The drugs themselves, the form of the drug, is essentially the same," she said.

On Tuesday, Durbin said the legislation, if passed, would eliminate "one of the most indefensible disparities in our system of justice."

Americans have been using cocaine, in its powder form, since the 19th century, but crack cocaine did not become prevalent until the mid-1980s.

Unlike powder cocaine, which can be injected, snorted or swallowed, crack cocaine is smoked.

Alarmed by crack's rising popularity and fearing it was more potent and more addictive, Congress passed legislation increasing penalties for its sales or possession.

Under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, a first-time offender convicted of possessing 5 grams of crack cocaine would be treated the same way as a first-time offender possessing 500 grams of powder cocaine.

Five grams is the equivalent of a few sugar packets; 500 grams is more than a pound.

Experts now say that the two forms of cocaine are pharmacologically the same.

Under federal law, those convicted of possessing 5 grams of crack faced a mandatory minimum of five years.

Rather than eliminating major drug traffickers, the law rounded up thousands of minor dealers and users and locked them up, Hutchinson said.

"This sentencing disparity approach rarely led to the incarceration of drug kingpins as its proponents hoped," Hutchinson said in written testimony he submitted to the committee. "Instead, the majority of those incarcerated were mere street-level users and sellers."

The five-page document emphasized the law's disparate racial impact.

"U.S. Sentencing Commission data show that in FY [fiscal year] 2009, 79 percent of defendants in crack cocaine cases were Black, then 78.5 percent in FY 2010, and 83 percent in FY 2011. More recently, in FY 2019 and FY 2020, 81.1 percent and 76.8 percent of defendants were Black. Yet survey data show that, in fact, crack cocaine users are predominately White," he wrote.

Hutchinson has been voicing concerns about the disparity for more than two decades. In 2009, he appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee and urged its members to address the issue.

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the disparity in the way powder cocaine and crack cocaine are treated.

Durbin, who supported the 1986 legislation as a junior House member, wants to see the gap eliminated entirely.

"It has no basis in science. It's done nothing to make you safer. It serves only to undermine trust in our system of justice, especially among Black Americans who are six times -- six times -- more likely to be imprisoned on drug charges than white Americans, even though the drug use is at a similar rate between them," he said.

Booker, the bill's sponsor, called it "a shameful chapter" in American history.

During committee questioning, Hutchinson emphasized the importance of addressing the issue.

"I think ... one of the most important things we could do to build confidence in our criminal justice system and with law enforcement is to equalize that treatment between powder and crack," he said.