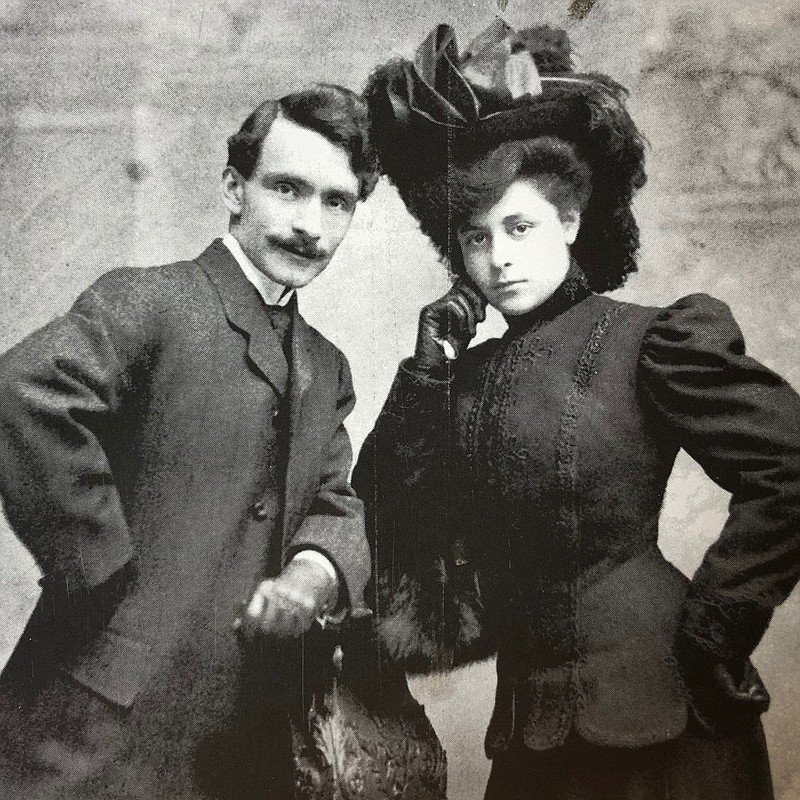

The front cover of the latest issue of Flashback, the quarterly magazine of the Washington County Historical Society, has a striking photograph from the early 1900s of the newly named UA Romance languages professor Antonio Marinoni and his flamboyant wife, Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni. Over the following decades Antonio and Rosa would become important educational and literary contributors to Fayetteville and all of Arkansas.

Antonio Marinoni and Rosa Zagnoni were natives of northern Italy. They were well educated. Rosa came from a literary family, her mother being a poet and artist, while her father was a newspaper correspondent and drama critic. One of her maternal uncles, Frederico Marzocchi, was a poet of considerable renown.

Antonio was completing his college work when his family moved to America, joining the rapidly growing Italian American population of New York City. Antonio soon joined the family, and though he was fluent in several languages, he knew no English. He quickly taught himself enough to be accepted into a graduate program at Yale University.

Blessed with a likable personality and movie-star good looks, Antonio did well at Yale. He then taught at Columbia University for a year. When the University of Arkansas contacted Columbia in 1905 in a search for its first professor of Romance languages, the faculty recommended the young Italian immigrant.

Writing several years later, Antonio told of his excitement as he rode the train westward: "... my face was stuck against the window looking for Indian villages with Indians wearing feathers in their hair." Though he found no Indians, Antonio discovered he liked the people of Fayetteville: "There was a difference in the way they acted and the way they talked compared to the nervous and perpetually agitated ways of the East where everyone subconsciously assumes a position of self-defense against everybody else."

According to John Marinoni of Fayetteville, Antonio's grandson and family historian, family stories tell of the young professor visiting his parents in New York during summer breaks and working up the nerve to court "the prettiest Italian girl in New York." They were married in July 1908, with Antonio commenting later "... I see that the apex of my American dream was reached the day I came back to Fayetteville with my faithful wife and companion, the beautiful Rosina Zagnoni."

While Rosa has eclipsed Antonio in Arkansas literary history, he was no slouch professionally. Antonio wrote several textbooks on learning Italian and French, some of which are still available online. After World War I, Antonio was detailed to the European Red Cross where he helped with post-war recovery. With Rosa's help, he also led numerous summer tours of Europe until the advent of World War II.

Like her husband, Rosa blossomed in Fayetteville. She settled in quickly, becoming active in several good causes, including the women's suffrage movement in Arkansas. She threw herself into volunteer activities during World War I, promoting Liberty Loan drives in particular.

June Baker Jefferson, in a biographical sketch of Rosa Marinoni, wrote that Rosa began writing while she was hospitalized in 1925 following an accident. The woman in the next bed began singing a lullaby for her baby who had just died, a searing sight which prompted Rosa to begin writing about the human condition. June Jefferson reported that Marinoni "is said to have taken up her pen at that time and rarely set it down again."

Rosa had grown up in a family of poets, so it is not surprising that poetry would be her medium of expression. She also wrote any number of literary and biographical pieces, and became known for her epigrams--those brief poems or sayings which in clever ways express a single thought and which at their best end brilliantly.

Rosa Marinoni's work is accessible and meaningful today. I have several of her books in my library, but I could only locate "Timberline: Selected Verse," published in 1954 when Marinoni was at the height of her literary career. She ended the book with a short section titled "Fireflies," a collection of her sayings. "If our heads were put up at auction the bids of our best friends would greatly disappoint us," was my favorite.

Rosa Marinoni's work could be light and fun, but she often wrote of challenges affecting mankind. One of her most powerful poems--which has been often cited and anthologized--is 1938's "Shanty in the Ozarks," which tells of Tom, "who is tired of poverty" and going to the city to look for employment.

Tom's wife weeps as the family huddles around a fireplace which sputters smoke from the green logs. Holes in the windows are stuffed with wadded-up newspapers, one of which is loosened by a gust of cold wind and falls to the floor. The paper comes to rest, with bold headlines telling of unemployment, bread lines, and starvation in New York City and Chicago. "But," Marinoni wrote, "Tom, Molly, and the children/Have never learned to read."

She published more than 1,000 short stories in 70 magazines; her poems were published in more than 900 newspapers and other journals. On top of this, she authored 19 books--some translated into Italian and other languages. In addition, Rosa was an engaged parent in raising the family's two children (two others died in infancy).

Both Antonio and Rosa took sincere interests in Fayetteville and Arkansas. They gained American citizenship in 1913. In 1926 Marinoni established the University-City Poetry Club, which met at her home for 45 years. Among the poets whom Rosa mentored through the Poetry Club was Edsel Ford, a young man whose star was rising when he died prematurely in 1970. She was also instrumental in founding the northwest Arkansas affiliate of the National League of American Pen Women.

In 1948 Gov. Ben Laney proclaimed Oct. 15 as the first annual Poetry Day in Arkansas. In March 1953 Gov. Francis Cherry appointed Marinoni to the position of Poet Laureate of Arkansas, a post she would hold until her death in 1970.

Rosa is buried at the Catholic Cemetery in Fayetteville. Antonio, who died suddenly in August 1944 in New Jersey while visiting family and friends, had long planned to be buried at his family village in Italy. His body was stored until the war ended, then shipped to his hometown.

Tom Dillard is a historian and retired archivist living in Hot Spring County. Email him at Arktopia.td@gmail.com.