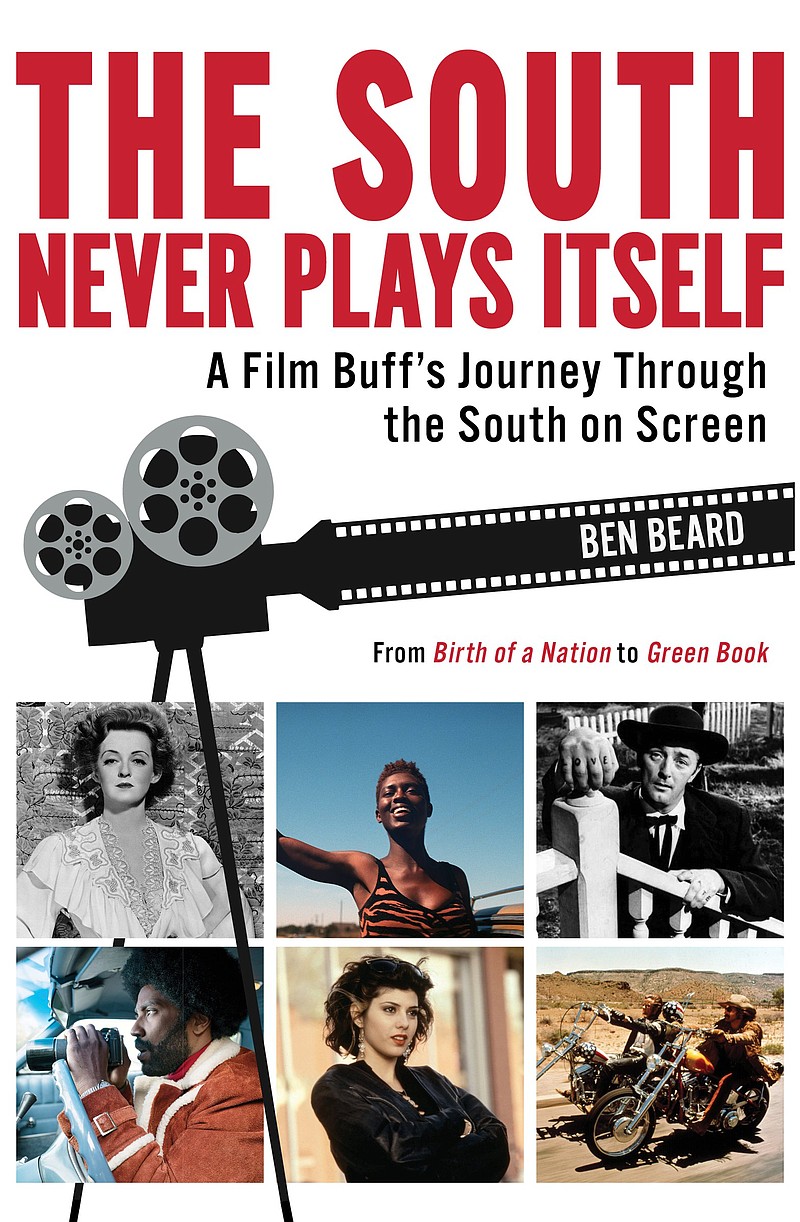

I don't know Ben Beard, but after reading his book "The South Never Plays Itself: A Film Buff's Journey Through the South on Screen" (New South Books, $28.95) I would like to.

Beard is a writer and editor, born in Georgia and reared in Pensacola, Fla. -- he memorably describes "the vibe" of his youth as "'Magic Mike' without the stripping" -- who grew up watching movies and taking them for granted.

Informed by the criticism of Pauline Kael and J. Hoberman, he took it upon himself to learn about the movies. Over a two-year period while attending grad school in Missouri, he checked out a classic film from the library to watch every night. That's one way to do it.

His book feels like an uncommonly readable text to a hypothetical college survey class on films of and about the South, which he recognizes as "both a region and thought experiment, real and fiction ... a place and an idea." He's right about that; every would-be Southerner constructs their own home, a South they can live in and with.

"Or else they get out," you might think, and knowing that Beard now lives in Chicago might seem to make that wisecrack feel, as Steven Colbert used to say, "truthier." Nowadays, Southernness is an act of volition; self re-invention is every American's birthright. But with some of us, Southernness is sticky; we believe in it the same way Flannery O' Connor believed in the Holy Ghost.

Part of being Southern is faith in the existence of the South which, as Beard points out, was no certainty before the Civil War. It tore apart the country but galvanized a region; the South became an occupied territory, defined by grievance and shame. "The North won the war, and the Union was preserved," Beard writes. "But the South didn't die; it had just ... been born."

As a Southerner, one has to grapple with depictions of the South that romanticize her lost cause and marginalize her people, reducing them to stock characters, to Ashley Wilkeses and Snopes and Hazel Moteses.

Like any decent white person these days, Beard finds D.W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation" as difficult to watch as it is indispensable. Griffith invented a lot of the grammar of modern filmmaking; he was also an opportunistic racist working to promulgate evil ideas designed to allow the ignorant to recast repudiation as martyrdom.

Beard is correct in assaying the movie as "dull," fascinating to contemporary crowds more for the novelty of its technology (Griffith was gambling that audiences used to sitting through 10-minute reels would have the patience for a film that ran more than two hours) than the quality of art.

Beard threads autobiography through his book; he remembers watching the notorious Disney film "Song of the South" (1946) half a dozen times as a child, and relies on his sister's recollection that he last saw it in a Houma, La., moviehouse in 1986, when it was given a second theatrical release. (Beard would have been 8 or 9 years old at the time.)

Since then the film has been hard if not impossible to see -- it has never been released on VHS or DVD in North America and is missing from the extensive library of Disney films available on the Disney+ streaming service.

The reason Disney made "Song of the South" disappear is well documented; when then-Disney CEO Bob Iger was asked about the film during a stockholders' meeting in 2010, he called the film "fairly offensive" and said the studio had no plans to release it.

Like Beard, I saw the film at some point in my past -- I have clear memories of certain scenes that blended 2D animation with live action, with cartoon bluebirds interacting with actor James Baskett, who played Uncle Remus -- but all my opinions about it come secondhand.

Beard allows that the film fills him "with dread and shame," with a sort of survivor's guilt that is one of the defining characteristics of the Southern psyche.

While it's always easy to find omissions and works you wish a critic had discussed, I'm surprised that while Beard touches on important recent films such as Benh Zeitlin's "Beasts of the Southern Wild" (2012), Barry Jenkins' "Moonlight" (2015), Debra Granik's "Winter's Bone" (2010) and Jeff Nichols' "Mud" (2010), he doesn't mention Nichols' "Loving" (2015) or his remarkable debut "Shotgun Stories" (2007), or Scott Teems' "That Evening Sun" (2009) or North Carolina-born Rahim Bahrani's "Goodbye Solo" (2007) or "99 Homes" (2015).

All of these would seem to be essential to any understanding of contemporary Southern filmmaking. ("Beasts, "Shotgun Stories," "Loving" and "That Evening Sun" all won the Southeastern Film Critics Associations' Gene Wyatt Award for best Southern film; "Goodbye Solo" was a runner-up.)

Still, Beard is an insightful critic and film historian, and "The South Never Plays Itself" -- the title is a play on film professor Thom Andersen's video essay "Los Angeles Plays Itself" -- is a thoughtful and serious exploration of the way the South is depicted and presents itself, and what that means to the people who have escaped the stereotypes of place and those who can't.

It is, like the middlebrow films that Beard believes the highest and best use of Hollywood's art and science, both a healthy self-assessment and a reason to have "hope for the future of movies, if fear and trembling for the future of everything else."

The arc of reality mightn't often bend toward happy endings, but we'll always have the movies.

Email:

pmartin@adgnewsroom.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

More News

“The South Never Plays Itself: A Film Buff’s Journey Through the South on Screen” (New South Books, $28.95)