Chloé Zhao's contemplative "Nomadland" begins with a woman named Fern (Frances McDormand), going through the contents of a storage locker somewhere out in the snowy plains. Picking through a box of clothes, she comes across an old jacket, and the sudden catch in her movement is enough to key us into how important this particular garment is. She holds it up, appraisingly, as a look comes across her face we will grow accustomed to as the film progresses -- something sternly wistful. She smiles, but it's a loaded sort of expression, filled with layers of memory and feeling and, we come to quickly understand as her eyes well up, pain. It's a brief moment, as many such moments are in the film -- Zhao's camera not overly punctuating the scene by making it obvious -- and it comes with no further explanation. If you're paying close attention, however, you don't really need to know the details.

As we continue to watch Fern's journey across the western United States over the course of a year, finding intermittent work -- she is quite industrious, and her wanderlust isn't a product of fecklessness or being idle; as she puts it later to a woman working at a state employment agency, "I like to work" -- Zhao's film never betrays the dignified simplicity of its protagonist by giving her a "life's journey" arc, ending with her either falling in love (the most obvious possibility), finding a permanent "home," or getting a dog (all of which Zhao teases us with in the course of the narrative).

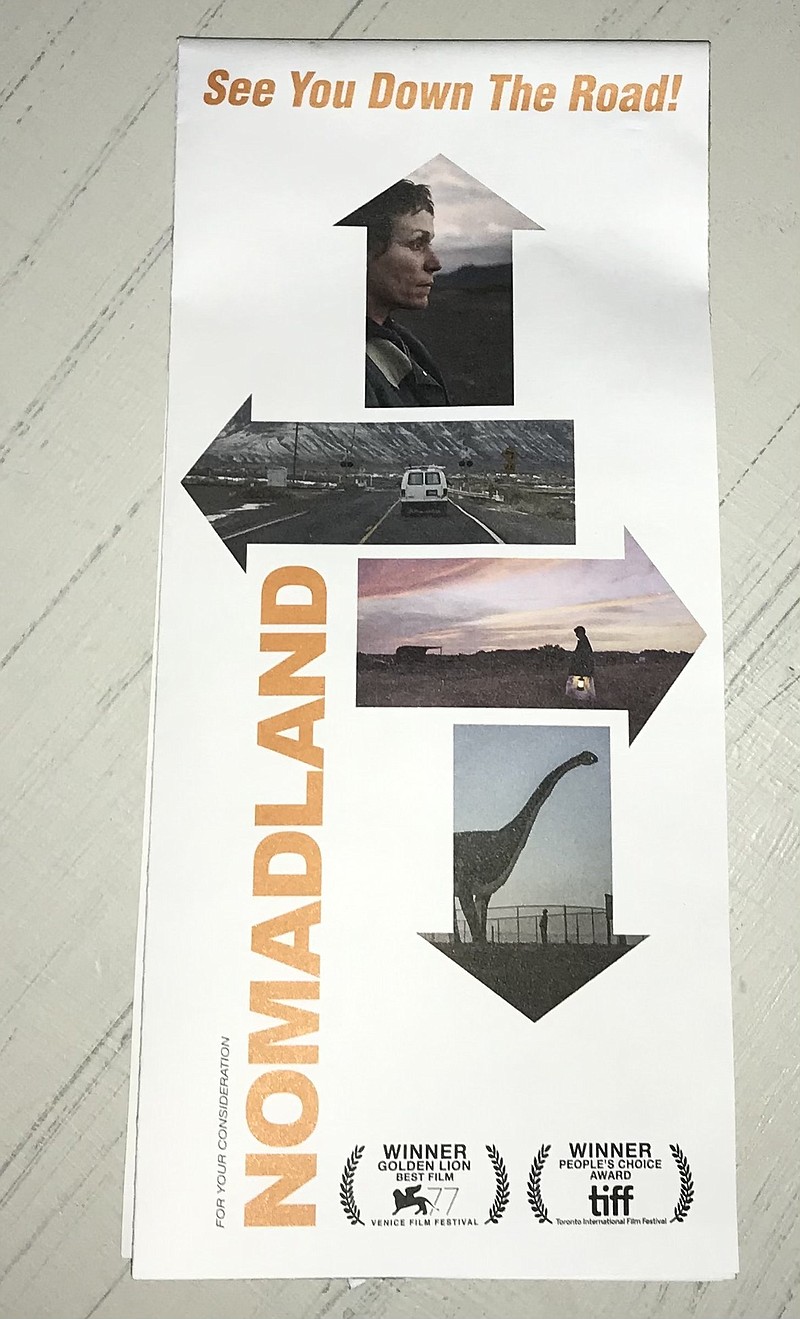

There is no driving force in the film other than Fern herself, literally moving from place to place in her beat-up van. Instead of overly familiar emotional beats or plot histrionics, Zhao has crafted a film that moves as lithely and unperturbed as Fern herself, creating a film whose frictions are crafted out of its visual poetics, and carefully considered storytelling. The result is a movie that's endlessly fascinating and evocative, while based on a character whose stubborn intransigence is entirely the point. Just how did she pull off this magic trick? Let's explore.

Sparsity is a choice. In making a movie about a vagabond woman whose relationship to the accumulated detritus of her life is ambivalent at best -- the only item she seems to prize, other than that jacket and her van (dubbed "Vanguard"), is a collection of old, ornate plates that her father sought out in flea markets and left to her -- Zhao has kept her film similarly disinterested in material goods. In one scene, Fern and some fellow nomads walk around an RV expo, stepping inside one of the luxurious, apartment-size vehicles, and mock it for its opulence. The film is much less interested in interiors, even those of its primary characters -- as we're never privy to Fern's actual meditations, she's as much of a cipher as a mountain dune -- than it is the expansive, lush exteriors of fading desert sunsets, and harsh winter fields. In making the characters' material frugality the symbolic mechanism behind the film's aesthetic (by the end, Fern abandons the rest of what little of her personal artifacts remained in her storage locker), Zhao has crafted a film that reflects perfectly her protagonist's philosophy.

Pacing out. Keeping with the idea of a muted dramaturgy, Zhao, who wrote the screenplay loosely based on the nonfiction book by Jessica Bruder, keeps our interest in part by fast-pacing the length and breadth of her scenes. None lasts longer than a few minutes, and she uses the character's varied journeys and differing locales as a means of keeping her audience alert to the abrupt shifts in place. In one such transition, the film cuts between a broad shot interior of a giant Amazon warehouse, a maze of industrial cranes, tubes and conveyor belts, to a simple, over-the-shoulder, outdoor hand-held shot of Fern, carrying a sack of laundry down a worn path in her RV park. By constantly switching settings -- in tone and location -- Zhao keeps her film percolating. Again, in harmony with its protagonist, the film never sits for too long on a moment.

McDormand's mien. Zhao, whose previous film, "The Rider," incorporated nonactors, more or less portraying themselves exclusively, does allow here for a couple of Hollywood veterans, McDormand and David Strathairn, and she makes the most of them. McDormand, in particular, her hair cut in a messy bob and her features now deeply etched on her face -- she looks remarkably similar to her early days as an actress, only with deeper contours -- is able to convey a tremendous amount of information with just the shift of her mouth or a subtle narrowing of her eyes. So much of the film, in fact, is Fern looking out over whatever living canvas she's spending time in; it was an absolute necessity for Zhao to find an actress whose every facial tic informs the audience. We don't get to see much of her inner life, so her outer one is essential to our understanding of the character.

Sumptuosity. There are a great many things that are wonderful in this film, but first and foremost the cinematography by Joshua James Richards is absolutely extraordinary. It's not just that the film makes such tremendous use of dusk and dawn lighting (which it most certainly does), or finds the exquisite beauty in everything from a desert vista to a refurbished can-opener. Because the sense of place is so strong and well developed, and because Fern takes it in at all times, it forces us to appreciate these things in her life as well. In this way, it has the opposite (and far more beguiling) effect of a film such as "Crazy Rich Asians," which seeks to overwhelm your senses with an endless string of pompous ostentatiousness. Zhao asks us to see the world the way Fern does, in its simple, glorious majesty. Richards' camera work is sublime, and his use of natural light, combined with Zhao's lilting frame, gives the film a sense of real grace.

Docufeel. With the aforementioned exceptions, the film is mostly populated by real people playing themselves -- one character who is stricken with cancer is in fact played by a woman with the exact same malady. Most of the cast use their real names. One of Zhao's tremendous gifts is to create an atmosphere in which real people are made to feel comfortable in revealing their lives in front of a camera. Because McDormand's affect is so flat to begin with, she blends right in, but the lives we are witnessing are largely real, which adds even more of a wistful keen. In keeping with the conceit, Zhao makes much use of hand-held shots and natural light, which only adds to the documentary vibe.

Nontraditional Narrative. "Nomadland" dispenses with the sturdy three-act arc. Fern begins the film perhaps a bit more attached to her past-life possessions than she does by the end (we can assume, since she doesn't seem to have that jacket with her; when she releases the contents of her storage locker, her late husband's artifacts are included with everything else), but this isn't a narrative that sets us up for any sort of grand conclusion. Fern doesn't seek the open road because she's heartbroken, or afraid of attachment, or in denial about her feelings -- or, perhaps, that's exactly what she's doing, but either way she sticks by her convictions. In a conversation with her sister (Melissa Smith), whom she has to visit midway through the film, it's revealed that Fern essentially was always the way she is now ("You maybe seemed weird, but it was just because you were braver and more honest than everybody else"). In lieu of the typical arc of change, Zhao keeps her protagonist more or less intact, and instead, asks the audience to change, in terms of their perceptions of her. When we first see Fern holding that coat, we assume she's moving around so much to try and fill the void that's been left in her life. We might think she must feel lonely, and want something more permanent to hold onto; but as the film continues, it's clear she does not. She's fine with her choices: Even if other people want something different for her, she's not particularly interested in our concern. Some people's lives, it turns out, don't follow a neatly delineated road map.