Alberta Miller refused to go on a ventilator at first.

The 68-year-old Blytheville resident who had survived Hurricane Katrina insisted to her pulmonologist that she could fight off the covid-19 virus that had ravaged her body for the past three weeks.

"My mom is a fighter. So she's thinking 'no' means, 'I'm going to continue and get better,'" said Key Fletcher, deputy director of the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center. "She's not thinking that the ventilator is the only option."

It was early January, and her doctor in the covid-19 intensive care unit at St. Bernards Hospital in Jonesboro was out of alternatives.

He told her she was working hard, but it wasn't enough, she needed to try the machine. She finally agreed and the family was called to her bedside to talk to her before she went on the ventilator.

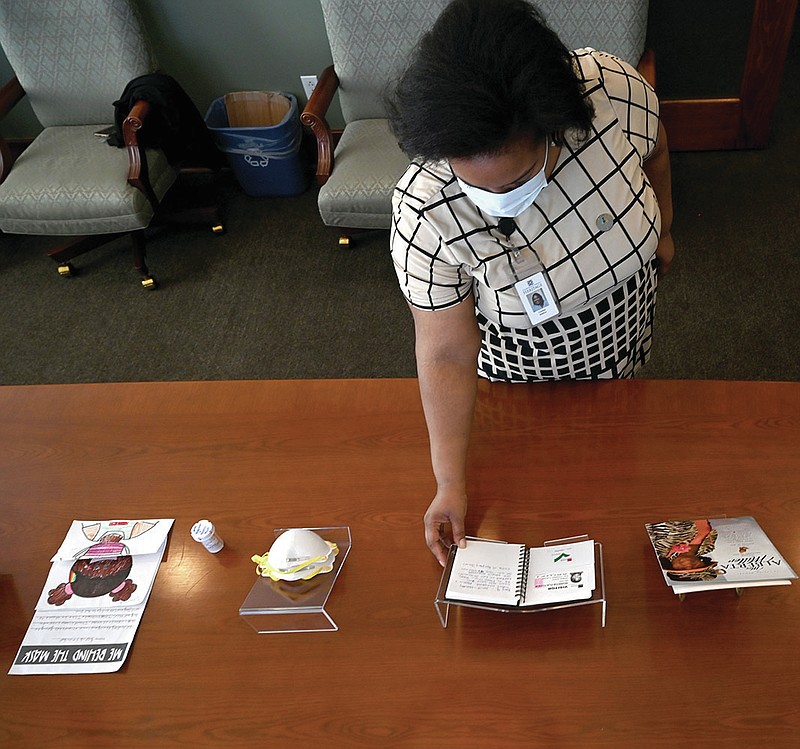

Nearly two months later, Fletcher was in the Mosaic Templar's conference room, looking over items splayed out on a credenza: face masks, a hospital visitor's pass, funeral programs, covid-19 pamphlets, handwritten letters.

Fletcher picked up her late mother's small black notebook from the display.

"Mom had so much pressure going into her because of the oxygen, that it was difficult for her to talk. So she wrote little notes to us," Fletcher said, reading from the notebook. "She's scared. She's asking us questions about the ventilator."

"Will it hurt?"

"Will I know what's going on?"

"How long will I be on this thing?"

Fletcher had donated the notebook and other items telling her mother's coronavirus story to the museum's "COVID in Black" project, which documents the experiences of Black Arkansans during the pandemic.

National data shows that the covid-19 pandemic affects Black, indigenous, Hispanic and other people of color more than whites.

The virus afflicted 10,876 people per 100,000 in the Black community in Arkansas, compared with 8,967 people per 100,000 in the white community, according to calculations by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette using data from the Covid Tracking Project, which stopped collecting data March 7.

Nationally, the Covid Tracking Project reported, the disease hit 5,822 Black people per 100,000, compared with 4,495 white people per 100,000.

As of Sunday, roughly 51,700 Black people in Arkansas have contracted covid-19 and 835 of them have died, according to the state Department of Health. Blacks make up about 15% of the state's population.

COVID IN BLACK

The Mosaic Templar's "COVID in Black, The African American experience in Arkansas" project -- which features videos, photos, written stories, audio recordings and items related to the covid-19 pandemic in the Black community -- doesn't have a timeline for its unveiling.

But the project won't be complete until the pandemic is over, said Christina Shutt, the museum's director.

In mid-March last year, the museum staff, like so many employees elsewhere, packed up their offices and went home to wait out the pandemic.

"That's when it hit us that we should be preserving this; we should document this in some way," Shutt said. "Initially we started with just staff documenting it, saving news reports, especially the stories about African Americans. After maybe a week or two of doing that, we said, 'We should ask other people to donate, too.' There was a consensus among the staff that this is important and this is something we don't want to miss."

The museum was awarded a grant from the Arkansas Humanities Council to hire Brian Mitchell, a history professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, to conduct research and document oral histories.

"We knew there were stories, like Key's, that we wanted to be able to share, that we wanted to be able to understand. From all walks of life," Shutt said.

News reports typically feature people who are most visible in society, she added.

"We came up with a list of people to try to really capture, 'How has this experience shaped us and how are we going to think about it 20 years, 30 years or a hundred years from now?'" Shutt said. "We're a hundred years from the flu pandemic. If someone looks back a hundred years from now, how would researchers think about how we handled it?"

An integral part of the project, she said, is also documenting activism for racial justice that has occurred simultaneously with the pandemic.

Protests broke out around the state and nation after the May police killing of George Floyd, a Black man, in Minneapolis.

"The pandemic as well as the ongoing march for social justice caused a lot of African Americans to run for office. We've collected items to show that," Shutt said. "African Americans are more likely to experience disparity as related to covid. There's all this scientific research about it, particularly around food deserts and other challenges that already existed."

Outside of covid-19 demographic data, Shutt said Blacks are more likely to be working in jobs that make them vulnerable to the virus, such as front-line grocery store workers.

"And now they're having to do it without hazard pay, without protection, without other safeguards in place," Shutt said. "They are putting, not only themselves, but their whole families in danger. Many were already living paycheck to paycheck before the pandemic.

"One of the things that we've all sort of learned, and picked up on, is that it's not that these things didn't exist before, it's that covid widened it. Covid made that chasm deeper for many in the Black community."

The pandemic hit the Mosaic Templars museum staff.

Last summer, an employee, who asked that her name not be used, contracted the virus and was hospitalized. She recovered and is back at work.

Kenneth Earl Brown Sr., the museum's site manager, fell ill with the virus and died Feb. 13. Brown gave special tours of the museum and told stories about the history of Ninth Street. He gave interviews to documentarians, historians and news organizations.

ALBERTA'S STORY

It was two days before Christmas when Alberta Miller found out she and her husband Curtis Miller, 66, were positive for the covid-19 virus.

Alberta was no stranger to tribulations. She and her family moved to Arkansas after Hurricane Katrina wiped out their New Orleans home in 2005. The hurricane caused about $125 billion in damage and killed more than 1,800 people.

Like Alberta, many of the survivors fled to shelter in Arkansas and never left.

"We always thought that the big story of the family would be Hurricane Katrina and being transplants from there," Fletcher, Miller's daughter, said. "But now, our story, our narrative is covid. It completely changed our story once again."

Alberta quickly acclimated to Blytheville, immediately finding friends and a home church that embraced the family.

"My mom is really a bubbly, optimistic kind of person," Fletcher said.

Alberta was symptom free, only getting tested for the virus because a friend had contracted it.

"We were in that phase where everybody knew tons of people that had covid," Fletcher said. "So when she called, I was like, 'OK. She's fine.' I told her, 'Y'all will just quarantine. It's like the flu. Drink your fluids, take your meds and you'll be fine.'"

Alberta laughed nervously, Fletcher recalled.

"Hey, God. Don't let anything happen to me," Alberta said.

Fletcher assured her mother that everything was going to be fine.

"And that's what we thought," Fletcher said. "We thought that she would be OK."

Three days later, Alberta's body was aching and she had a low-grade fever. She couldn't keep anything down and became dehydrated.

While Curtis Miller never developed symptoms, Alberta continued to decline.

Eventually, she was rushed to the hospital where she was given fluids and placed on a nasal oxygen cannula. The scans showed that Alberta had covid pneumonia.

"We didn't know she had pneumonia because she didn't have any symptoms," Fletcher said.

Alberta's oxygen levels plummeted, requiring 100% oxygen. They put her on a BPAP machine -- a non-invasive ventilation therapy device that creates bi-level positive airway pressure -- and her levels still did not improve.

It was time to move her to the intensive care unit, which meant a transfer from the small Blytheville hospital to St. Bernards in Jonesboro.

Still, her mother remained chipper and active.

"She's calling people, texting them, sending selfies of herself with her mask on," Fletcher said. "They're like, 'We can't get her off her phone.' People are so secretive and protective of anybody knowing they got covid. Not momma. She wanted people to be praying for her. She didn't keep secrets. There was nothing to her that was shameful or secretive about it."

A few days later, the doctor said it was time to call the family to her bedside before she was placed on the ventilator.

"This will probably be the last time you'll be able to talk to her," the doctor told Fletcher over the phone.

Fletcher called family members in Louisiana.

"We can't wait," the doctor told Fletcher when she made it from Little Rock to her mother's bedside. The family members who were on the road from Louisiana said their goodbyes through Face Time.

"In our brains, we never thought she wouldn't make it because our faith was so strong. We had people praying for her. We had people calling," Fletcher said. "We're just standing on the faith that she's a fighter. She's going to be OK."

Covid-19 is different from typical illnesses, though.

"It's crazy that they're saying, 'We're going to put your mom on life support and put her in a coma,' when there doesn't appear to be anything wrong with her," Fletcher said. "We were laughing and talking. It just didn't compute."

Fletcher began keeping a journal, documenting every day that her mother was on the ventilator and recording reports from the doctor. The medical team had told the family that if covid patients do not recover on the ventilator within five to seven days, they usually do not come back.

Fletcher counted the days.

"It's not making sense -- not only as a person of faith, but as a person who comes from a very resilient people. It's our culture. We can overcome anything," Fletcher said. "All of those things are in our heads, so we're very hopeful."

On Jan. 18, early on a Monday morning, Fletcher got the call that her mother's heart had stopped.

The medical team had tried to resuscitate her for 30 minutes already and was seeking Fletcher's permission to stop life-saving measures.

"Miss Fletcher, your mom's not responding. We need to call it," a nurse told her over the phone.

A PART OF HISTORY

Months later, during her interview with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Fletcher picked up her mother's funeral program from the credenza at the museum. From the front, her mother's smile beamed. She was wearing a zebra-print and peach-lined dress topped off with a matching hat adorned with layers of ribbon and a plume of feathers.

"That's my mom," Fletcher said, laughing.

Even as her mother was battling covid-19, Fletcher knew she would include Alberta's story in the museum's project.

"I was thinking, 'I want to keep this. I want to donate this to the project,'" Fletcher said. "I knew how important that was to be a part of telling the story of African Americans in Arkansas. So many people are hesitant to share. Even in my grief, I didn't want it to be for nothing."

Her mother, Fletcher said, would love that she is a part of history.

"She would love it that she's in a museum," Fletcher said, laughing. "My mom had an amazing testimony, not just in church, but outside of church. She was always one who was sharing her experiences, sharing her stories with others so that they could see, if she got through it, they could get through it, too. She lived a life that was well lived and her story had power in it."

Being a part of the museum's "COVID in Black" project, Fletcher said, is her mother's ultimate testimony.

"But testimonies don't always have happy endings," she said.

Information for this article was contributed by Ginny Monk of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.