We are divided, all of us.

You are in my head, attending as I write these words. You have traveled back in time a few days, or maybe months or even years if you have come upon this piece in an electronic archive somewhere. Anyway, at this moment, whenever it is, you are reading my thoughts.

But there is another you, one who sits and maybe holds a cup of coffee.

People call this dilemma, this duality of the self, the mind/body problem. Or mind-body dualism. Or any number of other things. Body and soul, if you like.

Rene Descartes thought a lot about this in the 17th century. He identified the mind as something apart from the brain — the mind was not subject to the laws of physics, it wasn't a spatial entity that could be located. It could float around the universe; it could imagine a private cosmos. It wasn't constrained by any physical bounds, not even that of our own bodies.

This is a big question. And I'm reviewing a picture book, a graphic novel by cartoonist Alison Bechdel, who used to draw a comic strip that ran in alternative newspapers and who has produced two virtuosic graphic memoirs: 2006's "Fun Home: A Family Tragicomedy," about her closeted father and his suicide, and 2012's "Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama" that focused on her relationship with her mother.

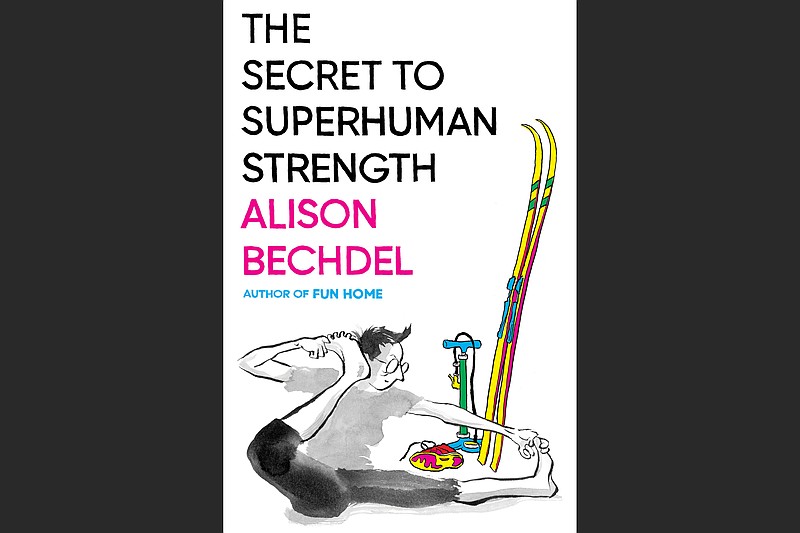

Her new book is "The Secret to Superhuman Strength" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $24) and the easy thing to say is that it is about her lifelong obsession with fitness and its fads.

What it's really about is her struggle to integrate her mind and body and how physical exertion has helped her.

Bechdel alleges she is no athlete, and her goals have never been cosmetic. What she's chasing is what a lot of us who have spent time in gyms and on fields occasionally glimpse: that certain emptying out of the ego, the blissful nothingness that athletic endeavor can sometimes return. The "high" that runners sometimes report, the sense of well-being that can envelop you when self-awareness falls away.

This is sometimes more easily witnessed in others more than ourselves, because when you zone out, you zone out. You become, as the sportscasters say, "unconscious." But maybe you live with someone addicted to exercise. Maybe you have seen them run or bike or lift and you understand that when they are in the moment they are not on the same plane as taxes and underwear and Zoom calls and parking tickets. They have escaped self-consciousness.

As a child, Bechdel discovered she could achieve this kind of trance state by tossing a tennis ball as high as she could and catching it.

"In time I learned that the secret to mastering the woolly orb was not to try. Not to think about it. Not to think at all," she writes.

And that is the key, isn't it? What your coaches and senseis and gurus always told you, to relax and let your mind go blank. Not only to not try so hard, but to not try at all. And to not try so hard at trying not to try. To get over yourself: that is the answer.

Bechdel discovers another path, skiing or biking or running past the point of exhaustion.

But it's not one of those hippy-dippy self-help manuals; it doesn't valorize working out for the sake of weight loss or body sculpting. There's an earnestness to her strength-seeking. She wants to be strong and is open-minded about how she gets there. She's mesmerized by the Charles Atlas ads in the backs of comic books; she gazes at TV's Jack LaLanne, forgiving him his sexist patter for his "cantaloupe biceps." She takes her title from an inscrutable pamphlet she sent off for when she was a child: "The Secret of Superhuman Strength."

She grows older and accumulates gear, eventually abandoning L.L. Bean for Patagonia, sturdy natural fabrics for high-tech ones. She reads Jack Kerouac's "The Dharma Bums," his account of a mountain-climbing trek with poet Gary Snyder, and, despite her impatience with his "macho" b.s., envies the way his ego recedes. And, as her sexuality gels, Andrienne Rich: "Two women, eye to eye/measuring each other's spirit, each other's/limitless desire,/a whole new poetry beginning here."

It's a lovely book and true insofar as what I know of chasing nirvana. And I haven't even mentioned the artwork, which is remarkably apt, and precise in that way some comic artists have of connoting what is specific and eccentric yet universally relatable. I regret having read the book so quickly, for you can miss things in the margins. "The Secret of Superhuman Strength" deserves to be looked over carefully as well as read.

And, as befits a comic, it is funny. Bechdel — who is most famous for lending her name to the Bechdel test, a measure of the representation of women in fiction that asks whether the work features a conversation in which two women talk to each other about something other than a man — has a shrewd and dry humor, and never takes the self she's trying to obliterate all that seriously.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com | blooddirtangels.com