WEATHERSFIELD, Vt. -- The morning sun was just slanting through the trees when a crew arrived with chain saws to remove the last sign of Romaine Tenney.

It was only a tree, a gnarled rock maple that stood for generations on the Tenney farm, and somehow survived what happened there on that September night in 1964.

Now Vermont had ordered the tree cut down. A saw began to whine, and clouds of sawdust filled the air. Then the first limbs began to fall, light and springy, coming to rest in a shower of twigs.

A dozen townspeople stood watching, mourners at a graveside. The tree was mostly dead, but they associated it with Tenney, the bachelor farmer they had called "Whiskers," and who had died in such a terrible way.

They were old enough to remember when the interstate was built, on land taken from farmers up and down the Connecticut Valley. The state offered compensation, but if landowners refused, it could seize land by eminent domain.

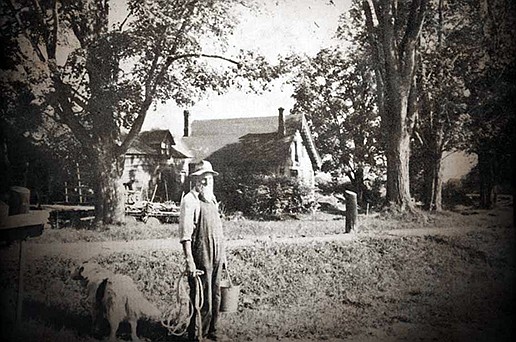

Plenty of farmers grumbled about leaving, but Tenney simply refused to go. Throughout the summer of 1964, bulldozers leveled much of the land around his farmhouse, but Tenney kept milking his cows, as if nothing was happening.

In September, a week after Tenney's 64th birthday, state officials authorized local authorities to remove him from the property. The sheriff arrived with deputies to empty his barn, piling his harnesses and plows and tools in a meadow.

That night, Tenney's brother implored him to make a life somewhere else, recalled his niece, Gerri Dickerson, 71. The highway department had told him it would be his last night in his house.

"What I remember is that he and Daddy were talking and tears were just rolling down Romaine's face," she said. "It was the eleventh hour, as they say. There had been so much agitation and grievance. The workers couldn't get where they had to get because Romaine would block the way."

"In his mind," she said, "the only way out was to do what he did."

Rod Spaulding was a volunteer firefighter at the time, and he remembers being awakened by a siren around 3 a.m. the next day. He stumbled outside, looked up at the sky and saw, as he put it later, that it was "just one red fireball." The fire was raging 60 feet into the air, seemingly from many directions at once, barn, sheds and farmhouse.

He heaved on the door to the room where Tenney slept, and realized, through the haze, that it had been nailed shut. The heat was so intense it melted the bubble light on the top of the fire chief's car.

John Waite, who was 12 at the time, had run to the scene with his father, joining a crowd of spectators. "What I remember most is just being awestruck," he said. "I could see the reflection of the flames on people's faces. That's one of the things I remember. Everyone's face was lighted up with these flames."

The ruins of the farmhouse were too hot to approach the next day; if you looked into the cellar hole, you could see metal glowing red, people said. When they could finally enter, the firefighters found evidence: an old bed frame, a rifle with expended shells. And bone fragments.

Tenney's remains were never identified; the ashes were dumped in the woods. The day after his memorial service, the state's attorney gave permission to the highway engineers to fill in the house's cellar hole, and construction on the highway resumed.

Tenney's shocking act was national news, resonating with Americans who were watching the countryside rapidly transformed.

Over the years that followed, new highways pumped outsiders into Vermont by the millions, and sentiment began to turn against unchecked growth. Tenney would take on the proportions of a folk hero, the subject of poems, ghost stories and at least three country music songs.

In the village of Ascutney, where Tenney lived, the loss was personal. Dwight Jarvis was 9 the year of the fire; he grew up next door. The two of them would sit on a wagon for hours, practicing flipping jackknives so that the blade lodged in the wood.

The night of the fire, Dwight stayed up watching till morning. He couldn't accept that Tenney was gone, not then, and not for a long time after.

"Us kids all thought he was alive and up in the woods somewhere," he said. "We just couldn't bring it to our minds that he burned himself."

Sometimes they would leave plates of hot food in the woods, just in case Tenney was out there, hungry. "It was almost like leaving something for Santa Claus," he said.

The highway brought change in a great rush. The village green was clear-cut and bulldozed, the wooden bandstand taken down, the dirt roads paved and widened.

In their place appeared the generic landscape of an American highway exit: service stations and highway signs, motels and mobile homes, the staccato of jake brakes on 18-wheelers. Romaine Tenney's farm would be the site of a Park and Ride, where commuters could park their cars and board buses into Hanover.

DeForest Bearse was 8 the year of the fire. Her house was near Tenney's, and every time the highway engineers detonated an explosive charge, it shook. Her brother hung a pencil from the ceiling of the living room, over a sheet of paper, so that with every blast, it would leave a mark.

"I can still feel what he felt," she said. "That feeling of utter hopelessness, when your life changes and there is nothing you can do about it."

Every few years, Tenney's story was retold by journalists or historians, and for all its horror, it was also a source of pride, a display of New England flint. People read Tenney's struggle as a metaphor for their own -- against Congress, against development, against taxes, against modernity. The villagers may not have protested in 1964, but now, a core group of them are fiercely protective.

That is what the state of Vermont discovered in 2019, when it announced plans to cut down the dying tree. The state's Agency of Transportation, aware it was treading on sensitive ground, invited locals to a public meeting, to discuss replacing it with a historic marker, an official state recognition of Tenney's story.

The meeting, which was covered by the news site VT Digger, didn't go as planned. One after another, neighbors stood up in the tree's defense.

"Let it die by itself, rather than by the chain saw," said John Arrison, an electrical contractor who is also a town selectman, justice of the peace and weigher of coal.

Dylan Romaine Tenney, 27, the farmer's great-nephew, said the family deserved an apology from the state of Vermont, something that had never happened.

And David Fuller, another selectman, said he could understand how Romaine Tenney felt. He himself had been forced to sell his herd of dairy cows, as a great wave of family farms were wiped out by a slump in milk prices.

"You said early on you wanted to find a way to honor Romaine Tenney. You can't," he said. "I'm telling you as a farmer I felt the same way when my cows left. You can't do it. And the town can't do it. You took something from him."

The official sent to speak at the meeting was Kyle Obenauer, the historic preservation specialist for Vermont's transportation agency. He explained that the tree, now on state land, was in an advanced stage of decay, meaning that its limbs could come crashing down on vehicles or people.

"We were aware of the history of the tree and Romaine Tenney, and we did expect that it would be a tough issue," he explained. "But it was a real serious threat to the people who used the Park and Ride."

Removing it and placing a marker there, he said, "is some resolution. That hasn't happened since Romaine Tenney's death."

The town pushed for a second opinion from Lee Stevens, an independent arborist, who said he initially thought he could find ways to prolong the life of the tree -- "the poor guy," he called it.

He could bathe its root system with moisture, shear off dying limbs, use a growth retardant to redirect its energy from canopy growth to root production. "The people were so involved with the tree," he said. "I just thought it was worth the effort."

But then another growing season passed without further action, and Stevens concluded that the window of opportunity for the tree had closed.

The state offered him the chance to bid on the removal contract, but Stevens didn't have the heart to do the job.

"I didn't want any part of that," he said. "Sometimes we have to put our chin up in the air and walk away."

In its day, the tree's canopy had extended 50 feet, a colossus under which Romaine Tenney and his sisters and brothers grew to adulthood.

Sprouting before the turn of the last century, it shot up, growing as much as a foot a year, for four decades before poking its crown above the tree cover and into the sunlight. At its full height, said Ted Knox, an arborist, it measured 85 feet and weighed 10 tons.

Then the parking lot was built, and, exposed to beating sun and hot asphalt, the tree began to weaken. The state's assessment reported "severe rot and decay, recent shedding of crown branches, and several leaders with the outer bark covered in fungal fruiting bodies."

Knox's crew showed up just before 8 a.m., and began its work before a handful of spectators.

There was Spaulding, the firefighter, now 79 and wearing a hearing aid. Fuller, 63, was there with the police chief and the fire chief. Bearse, 66, in a green tweed skirt and duck boots, stood beside the trunk for a few moments, almost close enough to brush it with her fingers.

Then the removal began and they all stood back to watch.

At first it was light work, lopping off radiating branches that made up the tree's crown. The outline of the tree vanished piece by piece, exposing patches of sky. Then the climber was releasing 300-pound lengths of wood that burst and split when they hit the ground.

By 9 a.m., all that remained of the tree was 6 thick feet of trunk, as bare as a thumb.

When the crew ran chain saws all the way through the trunk -- it measured 40 inches in diameter -- nothing happened. The maple stood impassively.

Workers pounded felling wedges into the split, looped a line around the tree and began to tighten it. Then they backed up to a safe distance, and, with a creak and a thud, what remained of the Tenney tree came down. It rolled once, kicked forward by the force of its own falling weight, before stopping.

The last few spectators dispersed to the warmth of their cars.

Bearse took a branch to work with her to put in a jar of water, on the off chance that it would bloom. The Tenney relatives, now scattered across the country, had asked for pieces of the wood. Fuller went home empty-handed, thinking about all the things that were gone and would never come back.

A few days later, the town sent an employee to groom the space for the Romaine Tenney Memorial Park, a grassy lawn with a pavilion, a memorial plaque and a picnic table, funded with a $30,000 grant from the Vermont Agency of Transportation.

The job went to Steve Smith, who moved his excavator over from his house, on part of the old Tenney property.

Smith had been 8 the year Tenney died. His father was the superintendent for that section of the highway, and he used to tell stories about resistance from the landowners, including one farmer who shot a hole through a surveyor's hard hat. That was his father's world, the blasting and the crusher plants and the workers out all night, greasing equipment.

But when Smith, now 64, stood on the spot where the Tenney tree had been, he found himself unable to give the order to remove the stump.

Recalling this moment, he choked up and had trouble speaking.

"Everything else had been taken from him," he said, by way of explanation. "That's where the tree was. That's like a gravestone. It's a mark."

Smith apologized for getting emotional; he didn't know what had come over him.

After that, he did what he had to do to take care of Romaine's tree. He sealed the stump's surface with a thin layer of clear epoxy. He placed two rings of stones around it, and planted flowers. Under the ground, the root system would quietly recede and decompose, releasing its nutrients back to the earth.

"I just figured, why take that?" he said. "I wanted to save what was left. Just to leave something."