BLYTHEVILLE -- A few years ago, the only two hospitals left in rural Mississippi County were on the verge of closing.

Over the years, declines in population in the tiny Delta towns dotted across the county, like Blytheville, once home to a U.S. Air Force base, made it harder for the hospitals to recruit physicians, particularly expensive specialists in fields like cardiology or neurology.

So patients were forced to seek care in bigger cities, like Memphis or Jonesboro.

Revenue continued to decrease.

The future looked bleak.

All that changed over the past year or so after the two hospitals in the Mississippi County Hospital System adopted a telemedicine system developed by a Little Rock-based startup called Innovator Health.

The technology allows patients to interact virtually with internal medicine doctors and other specialists without having to travel for care.

It has been a lifesaver.

"Now we are stable," said Chris Raymer, chief executive officer of the Mississippi County Hospital System, which has a hospital in Blytheville and a smaller, critical access hospital down the road in Osceola. "There is money in the bank, and there is stability."

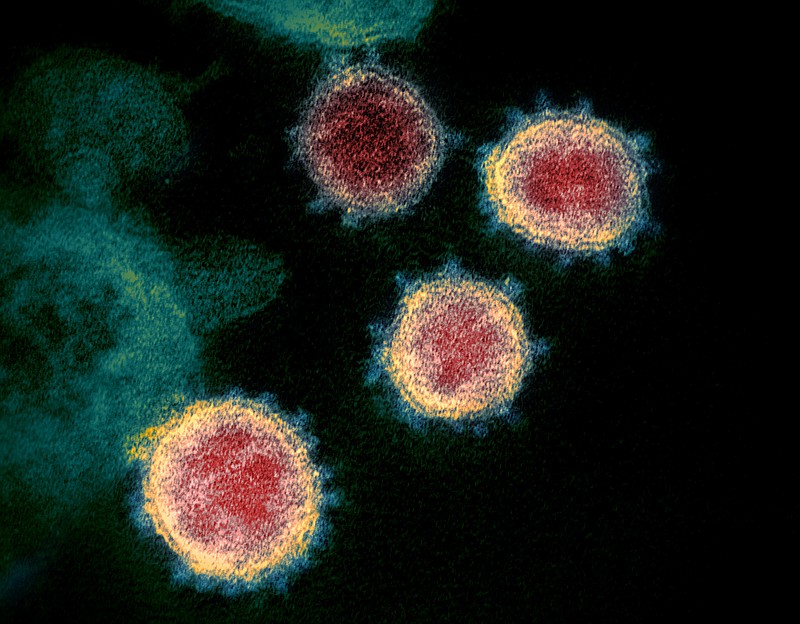

One silver lining of the covid-19 pandemic has been the rapid adoption of virtual health solutions in Arkansas as well as across the U.S.

As the virus ravaged, Arkansas doctors' offices were forced to all but close, and hospitals overflowed with people who were critically ill with the coronavirus, physicians had no choice but to find alternative ways to continue to treat patients.

In many instances, the only way to do that was with some type of telemedicine, which could range from a phone call to a videoconference to interacting remotely with a physician via a high-definition screen like the ones used in the two hospitals in Mississippi County.

That county's population declined by more than 6,400 between 2010 and 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

While these solutions are not new, researchers, physicians and public health experts say their widespread adoption during the pandemic is offering new hope to rural communities in places like Mississippi County in the Arkansas Delta where small hospitals and clinics have been vanishing for decades and where patients have to travel sometimes hours for care.

Such hospitals cannot afford to pay specialists and often do not have enough patients to justify hiring an oncologist, nephrologist or cardiologist, for example.

"It truly helps people in the rural, underserved areas," said Dr. Bala Simon, chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health. "It has been really important to close the gap in health care."

Between 2010 and 2020, 120 hospitals in rural areas across the U.S. closed, according to research from The Chartis Group, a health care advisory firm.

The year 2019 was the worst year with 19 closures, the study said, recommending that facilities explore ways to offer a "broader array" of services to retain patients and thus increase the bottom line.

Which is exactly what the telemedicine portal created by Innovator Health, called the Rounder, has enabled the hospitals in Blytheville and Osceola to do, Raymer said.

The Rounder consists of a cart containing a 55-inch, high-definition screen that is attached to medical devices, such as a stethoscope, that allows a nurse to examine a patient while a doctor interacts virtually in real time with the patient.

Patients who once may have had to travel to a larger facility for treatment can now visit virtually with doctors at St. Bernards Medical Center in Jonesboro, which provides internal medicine specialists for telemedicine visits at the Mississippi County hospitals.

This means the hospitals in Blytheville and Osceola can admit -- and retain -- more patients, and thus make more money.

Before obtaining the telemedicine technology at the end of 2019, Raymer said the Great River Medical Center in Blytheville might have six patients admitted on any given day.

Now, with the technology, there are few days when there are not at least 25 patients in rooms.

"By having telemedicine, we are able to get some of the top-quality physicians who don't live here," Raymer said. "We are able to provide high-quality physician care anytime and can keep more patients."

"It is on the verge of changing rural health care," Raymer said.

The major change that occurred during the pandemic with telemedicine is that because physicians had no choice but to use digital solutions, insurance companies, once reluctant to pay for such services, agreed to start paying for virtually all of them.

It is unclear whether the regulations approved at the federal level for Medicare and Medicaid coverage of telemedicine will remain in place once the covid-19 health emergency ends.

Private insurers in Arkansas also expanded coverage of telemedicine during the pandemic, and state legislators codified executive orders ensuring that much of that coverage will remain in place post-pandemic.

In Arkansas, covid-19 "probably moved the telemedicine football five years ahead to where it would have been otherwise," said David Wroten, executive vice president of the Arkansas Medical Society. "Now you see physicians carving time out of their normal day to see patients using telemedicine."

Simon, who in addition to being chief medical officer for the Health Department, works as a physician at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, said his clinic has seen a substantial increase in telemedicine visits over the past year.

"At the height of the pandemic, 50% of my clinic was via telemedicine," Simon said. "Now there are more inpatient visits but still 20% or more are telemedicine."

"Telemedicine is here to stay," he said.

In April, UAMS reported that it had conducted more than 100,000 digital health visits after the outbreak of covid-19 last year.

Now UAMS averages about 2,000 digital health visits per week.

Before the pandemic, only a handful of providers used digital methods for consultations. Since then, 1,090 UAMS providers have used digital visits to meet with patients.

"There has been an enormous amount of development immediately around the pandemic," said Dr. Joseph Sanford, director of the UAMS Institute for Digital Health & Innovation. "Our options and capabilities not just on the clinical side but on the tech infrastructure side have advanced quite a lot in a short period of time."

The UAMS Institute for Digital Health & Innovation works with hospitals around the state to provide telemedicine solutions that enable patients in smaller facilities with specific conditions, like strokes, to be evaluated remotely by a UAMS specialist.

But there still are limitations, namely access to high-speed internet, which leads some to question whether telemedicine is something that will be adopted at an individual level to allow patients in rural areas to use services in their homes.

"Broadband access is one of the big barriers," said Dr. Shane Speights, dean of the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro. "Good broadband infrastructure is essential."

The institute, in partnership with St. Bernards Medical Center and Innovator Health, has expanded telemedicine to rural hospitals in communities like Piggott, Pocahontas and Walnut Ridge.

It remains unclear how common the use of digital health solutions is outside hospital walls.

In urban areas, where internet connectivity is higher, patients have become more adept at having videoconferences, phone calls and even sending emails to doctors.

Studies showed that while telemedicine use increased in rural areas during the covid-19 pandemic, the rate of adoption was much higher in cities.

Naomi Cottoms, executive director of the nonprofit Tri County Rural Health Network, works daily with individuals living in the Arkansas Delta who often do not have broadband access, much less adequate cellphone service.

Many are also elderly and not accustomed to using such technology.

Based in Helena-West Helena, also in the Delta, the Tri County Rural Health Network uses community health workers to help socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, predominantly from communities of color, gain access to health care and other health-related services.

Cottoms said more people are using some form of telemedicine from home, but it is far from widespread.

She said many people without cars still rely on transportation services to take them to doctor's appointments in Memphis or Little Rock. "We do what we have to do to survive," Cottoms said.

"We still have areas where there is no access to internet, where there are barriers related to knowledge and understanding of how to use [telemedicine]," Cottoms said. "It is a grand opportunity, but access has to be improved."

All of this raises the question of what the limits to telemedicine are in rural Arkansas and if some barriers to access are entrenched in longstanding systemic inequities.

"I think that we have been so oppressed for so long that our hope, our dream, our vision of having more has just gone away," Cottoms said. "Inequities are so powerful that if we are ever able to overcome them the world we would live in will be amazing."