"Motorcycled" policemen were already a fixture on the streets of Little Rock 100 years ago. Had been for a decade.

No longer the "pop-pop squad" an Arkansas Gazette headline had laughed about in 1908, by May 1921 they were simply "the motorcycle cops." The word Motorcycle was part of the official title: It was "Motorcycle Patrolman" or, less often, "Motorcycleman."

Patrolman Burwell Conrad Rotenberry was Little Rock's pioneer motorcycleman. In May 1911, he learned to ride the department's first $275, 5-horsepower, twin-cylinder, Indian brand machine. The most senior patrolman, Rotenberry was efficient, according to the newspaper's City Hall column:

"Patrolman Rotenberry's duty will be to put the ban on speeding by local autoists. The purchase of the motorcycle was the result of the large number of complaints which were registered almost daily at police headquarters on account of speeding by automobile owners in Little Rock."

It also resulted from the fact that Chief of Police Frank McMahon had wanted one for years. Sadly for McMahon, he was replaced a month before the city bought the trendy traffic control tool (see arkansasonline.com/531squad).

After 29 days, the paper reported that the motorcycle had more than paid for itself, having brought in $410 in fines and forfeits. Rotenberry and Motorcycle Patrolmen C.F. Eby and C.C. Farmer had put 790 miles on it, using little more than 6 gallons of gas.

They did a startling job. Speeders committed carnage on city streets, they truly did; but the sight of cops unzipping the road at 25 mph or 30 mph did not necessarily reassure the public. A week after the news about all those fines, Farmer encountered a horse and buggy on the wrong side of Main Street. He lectured that driver for having almost forced him to stop. The man berated Farmer for speeding.

Farmer laughed about it with a reporter, because, yes, it was his job to speed.

Motorcycle patrolmen also suffered and inflicted injuries. The wood-block or gravel streets were crazy dangerous: wagons, buggies, trucks, horses, the occasional goat or rabid dog, kids, bicycles, clueless pedestrians, streetcars ... and autoists were forever running into motorcycles. Most of the many motorcycles that made the news were ridden and wrecked by civilians. But the motorcycle police — the few, the armed — were celebrities. If you didn't slow down, they might shoot at you.

Flash forward to 1921.

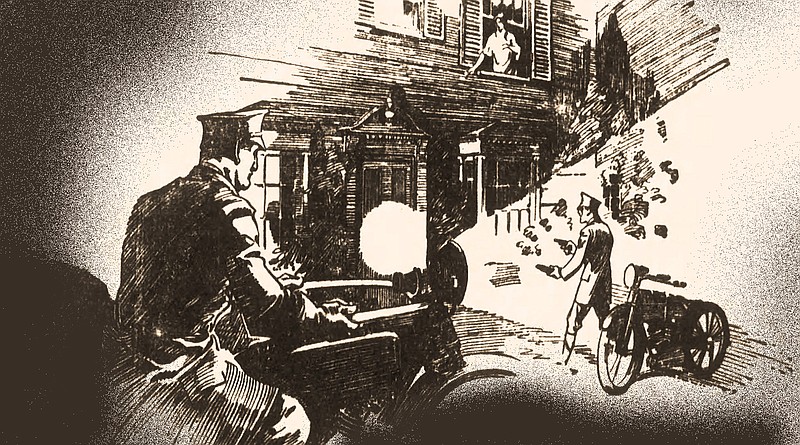

On May 4 the Arkansas Democrat reported that Motorcycle Sgt. A.A. Wright pursued a speeding Buick across the city, twice, at breakneck speed. Wright gave chase because the car zipped past him; he had no idea it was loaded with six 16-gallon kegs of moonshine.

He tried to pull beside the driver's door, but each time the car swerved as though to force him into the curb. He fired his gun, hoping to puncture the gas tank. He missed the tank but hit the back of the driver's seat.

■ ■ ■

Let's all pause to absorb the fact that in 1921 an automobile seat could stop a bullet.

■ ■ ■

Recoil jarred the motorcycle, and Wright grabbed the handlebars while holding his gun. The catch that held the cylinder in place opened, and all the cartridges fell out except one. Later in the chase he fired that bullet, again missing the gas tank.

This mayhem ended on the 19th Street Pike when the offending car slammed into a Chevrolet that was stopped beside the road near the Rock Street Bridge. Inside that innocent car, a visitor, Miss Bessie Griffiths of Tulsa, was seriously injured.

The offending car's occupants vanished. But Wright had the license number.

When the State Highway Commission office opened the next morning, he learned that the Buick was licensed to one Silas E. Wilson of Hot Springs. Wilson had reported his car stolen, but a grand jury didn't believe him. He was charged with driving "the booze car."

Photo Gallery

Motorcycles on the move

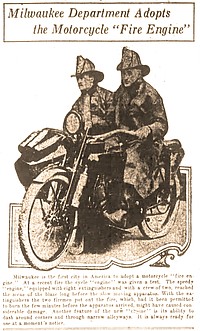

The Motorcycle & Allied Trades Association conducted a marketing campaign in 1921 under the slogan “Do It With a Motorcycle." Here are a few of the ads that appeared in the Arkansas Gazette. At the time, city police and fire departments were finding new uses for motorcycles and innovative ways to stop speeding.

In other 100-year-old motorcycleman news, on May 15, North Little Rock announced it had hired a second motorcycle cop, S.L. Kerr. Kerr replaced Patrolman N. Shaver, who had resigned May 12. Kerr joined Motorcycleman J.W. Talley in traffic control.

On May 21, a Pine Bluff patrolman was badly bruised when his motorcycle collided with an auto near Fifth Avenue and Cherry Street. Patrolman Wells Bond had been on his way to a fire.

On May 24, the Little Rock Police Committee set aside $410 for the purchase of a new motorcycle with a sidecar attachment. Just in time, because the city fleet was about to suffer two casualties.

About 3 p.m. May 28, Motorcycle Sgt. Wright, 519 Wolfe St., and Motorcycle Patrolman Wilmar D. Rhodes, 1616 Barber Ave., were painfully injured when the motorcycles they were riding collided — with one another.

Human interest note: We know that Rhodes was a married man and small, in fact, the shortest man on the force. On April 17, 1921, the Gazette published a photo of him posed beside the city's tallest policeman, a detective named T.L. Hooter. (See it in the gallery at arkansasonline.com/531vroom.)

Also married, Hooter was 6-foot-6 and weighed 247 pounds. His past employment included three years as a patrolman and many years as a hospital guard. He'd worked for 13 hospitals in seven states, especially mental hospitals.

Rhodes was 5-foot-6 and weighed 152 pounds. Before he joined the department in July 1920, he'd spent seven years with the U.S. Army, including duty in France, the Philippines and China.

Chief of Police Rotenberry (yes, the same Rotenberry who was the first motorcycleman) investigated. He said the officers had been motoring along the 19th Street Pike from opposite directions. They intended to meet, and both had slowed their machines when an automobile brushed past them. Wright swerved to miss it, but it struck Rhodes and he took Wright down.

Both motorcycles were damaged considerably. The automobile escaped.

WAIT, THERE'S MORE

Also that May 28, Motorcycle Patrolman William J. Haynie arrested Claude Bivens, automobile repairman, for speeding at 18th Street and Thayer Avenue — on a motorcycle.

Just that February, Haynie had spent a day and a half at St. Vincent Infirmary, lying in the bed next to the bed of the man he'd rammed with his motorcycle. Haynie was speeding after a police car on Capitol Avenue, headed to a domestic disturbance call (wife beating), and Fred Hodges was bicycling without a lamp. The Cook Drummond-Overman hearse gave Haynie a lift home Feb. 27. The paper didn't report whatever happened to Hodges.

And remember North Little Rock's new man Kerr? He suffered painful but not serious cuts on his head and face June 4, 1921, when his motorcycle struck a wagon as he rounded a corner from 17th Street onto Broadway. At the time, he and Motorcycleman Talley were chasing three speeding automobiles. Talley was in the lead and dodged the wagon, which was without a light and not easily seen.

After the accident, Talley and Chief of Police August Ganser went to the scene to collect the two machines. Ganser had his first lesson in riding.

"He admits he did remarkably well. The only thing he did was turn on the gas when he meant to turn it off, just as he was preparing to park in front of City Hall."

The machine didn't park. Instead, it reared and made for the pavement.

It takes nerves of steel to ride a metal horse.

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com