"Maybe we can express ourselves best if we say it without words." — Anjelica Huston in Wes Anderson's "The Darjeeling Limited" (2007)

It is obvious a movie is not a book or a song or a poem.

A movie is a play of light and sound, with a temporal dimension. It happens in front of us; its pictures are tangible and proffered, rather than inwardly created. While movie-watchers collaborate with the filmmakers to some extent — the final film is still the one that plays in the backs of our minds rather than in front of our eyes — a director presents us with a manifested vision, a built world, not just the raw materials from which we might puzzle one out.

We know what the worms and orinthopters look like in Denis Villeneuve's "Dune" because we have seen them, not just read their descriptions. This is a powerful advantage of film, one that even Tolstoy thought might obsolete the novel.

A filmmaker shows us what writers can only tell us. And these images move and consort and take on trajectories. If a picture really is worth 1,000 words, multiply that by 24 frames per second, by however many seconds are in your average movie.

So a two-hour film is worth 172,800,000 words. More than 400 times as long as Margaret Mitchell's 1,000-page novel "Gone With the Wind." It takes the average reader about 56 hours to read a million words. If the adage is correct, a two-hour film could deliver as much data as nine billion hours of book learning. Theoretically.

Not every filmmaker takes advantage of the medium's inherent bandwidth, and there are limits to what our brains will perceive. Sometimes it's counterproductive to cram a frame with irrelevant detail; even the most intentional directors sometimes must accept that their vision can only be incompletely realized. They must necessarily collaborate with pre-existing faces, shapes, colors and sounds.

'THE FRENCH DISPATCH'

A couple of weeks ago we saw Wes Anderson's "The French Dispatch" in a movie theater, on a big screen with good sound.

I was anxious about seeing the film. I am a fan of Anderson's work in that I often appreciate it because I flatter myself that I am able to see around the sides of it, that I get it. But I'm also aware that this insider-y appreciation of his work is not the same thing as genuine enjoyment.

Often while watching one of his films, I find myself thinking about things a moviegoer should not have to think about — which characters have been assigned which colors and how the youngest characters seem to be the only genuine adults in the play, willing and able to engage with the sorrows of the world.

It's like I'm carrying around a mental bingo card, blotting off points of congruence with other Anderson films. A labyrinthine, obviously artificial set (like the mountaintop hotel in "The Grand Budapest Hotel" or the research vessel Belafonte in "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou")? Check. Precise, metered dialogue just a few cents off stilted? Check. Funny hats? Check.

Like most Anderson admirers, my entry point wasn't his first movie, 1996's "Bottle Rocket" (though I have since gained an increased appreciation of it.) My gateway was 1998's "Rushmore," which has become a cult classic. But unlike a lot of cult classics, "Rushmore" isn't all cruel fun and snobbery.

It's the opposite of cynical, a movie about overt passion that is genuine and deserved as well as a kind of mask. Though it bears only the slightest resemblance to the story lines of these works, throughout the film I was reminded of Hal Ashby's 1971 romantic black comedy "Harold and Maude" and Martin Amis' first novel "The Rachel Papers."

"Rushmore" resembles the Ashby film in tone, and Amis' protagonist — though much meaner than Anderson's antihero Max Fischer (Anderson's chronic collaborator Jason Schwartzman) — has something of his mock-adult pretensions.

"Rushmore" might be divisive; it has a certain calculatedly belligerent edge likely to divide watchers into camps of the enthusiastic and the unimpressed. It's part of the cinema of the inside joke that has its roots in the ironic inventions of such '70s comedy icons as Monty Python, Richard Pryor and "Saturday Night Live." It's not so much a movie some people won't get as a movie designed not to be gotten by some people.

This is the case with a lot of of Anderson's films — if you wanted to, you could call them elitist. Or you could say that Anderson gives his audience the benefit of the doubt; he assumes they're smart, or smart enough. And by now, 10 movies in, you can be relatively confident that no one is going to a Wes Anderson movie by mistake.

That doesn't mean it always works for everybody.

[Video not showing above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/117anderson]

(UN)-ACQUIRED TASTE

While I am bemused by some of Anderson's whimsical tics, my wife, Karen, has little patience for them. She has disliked as many of Anderson's films as she has liked, and I don't believe she has ever cared for any of them as much as I love "The Royal Tenenbaums," "Moonrise Kingdom" or "Fantastic Mr. Fox."

She probably likes "Isle of Dogs" best; both "The Darjeeling Limited" and "The Grand Budapest Hotel" left her cold. I figured there was a real possibility she wouldn't be charmed by "The French Dispatch." She might even have been predisposed to dismiss it as trifling or "twee," to use a word she never would but that gets bandied about when critics are searching for a term to describe the sense of curdled innocence that permeates Anderson's films.

While I had avoided reading any reviews of "The French Dispatch" before seeing it (when I found out we were getting an advance screening in this market, I held off reading and editing the review I'd commissioned from Piers Marchant for this newspaper until after the screening), I couldn't help but be aware of the positive buzz surrounding the movie. Piers had enthused about it in the email that accompanied his piece; I'd heard some other reviews were quite favorable. Apparently NPR bubbled about the movie.

Then there were a couple of pieces that suggested it was more an aesthetic exercise than a full-blown movie. I went into "The French Dispatch" with more hope than faith.

And I will not say it is the "best" movie I have seen all year, for those superlatives always feel reductive and off-putting. But "The French Dispatch" is restorative; it is a tonic that refreshes my confidence in the ability of movies to matter in an almost spiritual way. It is the best time I've had in a theater in a couple of years, and it reminds me that there are reasons to see these things we still call movies in these special places where we don't have charge of the remote control and might not know our fellow congregants. It's fun.

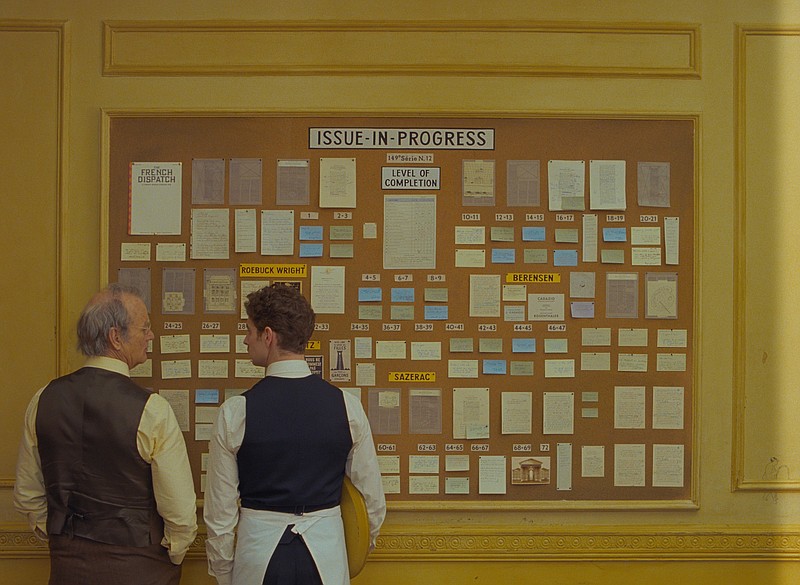

More than that, it is fantastic in the sense that we — or at least most of us — were drawn into a strange world with some recognizable markers of our own. Anderson exploits the medium's ability to crowd information into a shot, and composes his frames with tender precision and delicacy, splitting the difference between provocative painterly tableaus and the clinical coolness of someone like David Fincher or Christopher Nolan.

If you pause any of his movies at random, you are likely to find treasures in his storybook backgrounds (book titles, record spines, the "unaccompanied minor" badge that Kristofferson Silverfox wears in "The Fantastic Mr. Fox").

RECOGNIZABLE REALITY

But Anderson's world is based on a recognizable reality that he shares with his audience — he's not creating a universe like Frank Herbert did with his "Dune" series, or even like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which might share a few points of congruence with the world we know. Anderson's films take place in a world where bands like the Rolling Stones, the Kinks and the Zombies exist, for we hear their recordings in his movies. It's a different world, but is constructed of elements we might know (and love).

For example, "The French Dispatch" is a portmanteau film modeled on an issue of a magazine very much like The New Yorker in sensibility and typography. This magazine is based in a fictional French city called Ennui-sur-Blase, and various characters have obvious real-life inspirations.

Fictional writer Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) is based to some extent on the real-world writer Luc Sante. Bill Murray's character is based on Harold Ross and William Shawn, the New Yorker's first two editors. Tilda Swinton plays a lecturer based on art historian Rosamond Bernier — who the New Yorker called "the world's most glamorous lecturer on art and high culture." As Roebuck Wright, Jeffrey Wright manages a pitch-perfect James Baldwin impression.

And while "The French Dispatch" might work as a movie if the viewer has no inkling of the connection between these characters and their analogs, Anderson is working off the assumption that we likely will make these connections, and that our experience will be the richer for it.

The difference between plagiarism and allusion is that the plagiarist is counting on you not knowing the original, while the allusionist is counting on you knowing it. "The Royal Tenenbaums" is not only a riff on J.D. Salinger's Glass family, but if you know the stories, Anderson's narrative seeps in a little deeper.

I'm still not sure how I feel about the moment in "The Life Aquatic." Bill Murray's Steve Zissou, a filmmaking oceanographer obviously modeled on Jacques Cousteau, mentions the real Cousteau in passing. It feels a little dangerous, like smuggling a piece of reality-based antimatter into the Andersonian universe.

Someone who looks to write about the movies is always at risk at overthinking Wes Anderson's work. As a storyteller, he has shown little interest in confusing or misdirecting his audience. He wants to be understood, to be clear. And his characters are generally thoughtful people who take their work seriously and we might imagine he has created them in his own image.

All the trademarks — the symmetrical framing, the complex theatrical-style blocking, the generally respectful way the characters have of relating to one another, the production and costume design, the exactness of the dialogue (Bill Murray once said it was a relief to work on an Anderson film because the script always told him precisely what to say, while he was often expected to elevate other productions with ad libs and rewrites) — are susceptible to parody. Anderson is always walking a tightrope between presenting a singular vision and devolving into mannerism. In "The French Dispatch," he manages to transverse the abyss.

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

Not everyone will agree.

Most movies strike us as dull these days, we've all seen a lot. We either accommodate them with lowered expectations or look elsewhere for entertainment. This global pandemic has changed us in very real ways; we might find ourselves re-evaluating what we consider worth going out in the world to see. Our streaming services can supply us with the basics, even some exquisite stuff. Once again, the movies might have to reinvent themselves in the face of existential threat.

If so, events like "The French Dispatch" may be important to the movies' survival. While I'm sure Anderson could make a profitable television series — maybe an anthology — he seems best equipped to do just what he's doing: invite us into a world he has completely prepared for a couple of hours.

For a couple of hours I'm willing to let him show me what he wants to show, hear what he wants me to hear. And I will trust that he's the puppet master behind it all — that what I'm looking at is the closest distillation of his particular vision that can be practically achieved.

That's not entirely true; "Wes Anderson" is probably more properly understood as a brand, as a collaborative effort led by the director, than as the lone creative engine behind the films. But it is a tight and disciplined factory that pumps these things out and they seem to have a secret formula. They inject melancholy and philosophy into stories about gentle misfits and murderous artists.

I love them in a way I can't quite articulate. Which is probably the intended effect.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com