WASHINGTON -- A worsening surge of inflation for such necessities as food, rent, autos and heating oil is setting Americans up for a financially difficult Thanksgiving and holiday shopping season.

Prices for U.S. consumers jumped 6.2% in October compared with a year earlier, leaving families facing their highest inflation rate since 1990, the Labor Department said Wednesday. From September to October, prices jumped 0.9%.

Inflation is eroding the strong gains in wages and salaries that have flowed to America's workers in recent months, creating a political threat to the Biden administration and congressional Democrats, and intensifying pressure on the Federal Reserve as it considers how fast to withdraw its efforts to boost the economy.

"I expect lots of eyeballs were bulging out of their sockets when they saw the number come in," Seema Shah, chief strategist at Principal Global Investors, wrote in a note reacting to the October data. "Inflation is clearly getting worse before it gets better."

Fueling the spike in prices has been robust consumer demand, which has run into persistent supply shortages from covid-related factory shutdowns in China, Vietnam and other overseas manufacturers. America's employers, facing worker shortages, have also been handing out sizable pay raises, and many of them have raised prices to offset those higher labor costs.

Americans are now spending 15% more on goods than before the pandemic. Ports, trucking companies and railroads can't keep up, and the resulting bottlenecks are swelling prices. Surging inflation has broadened beyond pandemic-disrupted industries into the many services that Americans spend money on, notably for restaurant meals, rental apartments and medical services, which jumped 0.5% in October.

The accelerating price increases have fallen disproportionately on lower-earning households, which spend a significant portion of their incomes on food, rent and fuel. Food banks are struggling to assist the needy, with beef, egg and peanut butter prices jumping. Millions of households that are planning year-end travel, Thanksgiving dinners and holiday gift-giving will pay much more this year.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » arkansasonline.com/1111prices/]

The jump in inflation is hardly confined to the U.S. Prices have been accelerating in Europe and elsewhere, too, with annual inflation exceeding 4% in October, the most in 13 years, and energy prices spiking 23%. In Brazil, inflation soared more than 10% in the 12 months through October.

At the same time, the economy is managing to sustain its recovery from the pandemic recession, and consumers, on average, have plenty of money to spend. That is in contrast to the "stagflation" of the 1970s, when households endured the double hardship of high unemployment and high inflation.

Many Americans are also receiving pay raises, especially workers at restaurants, hotels and entertainment venues, where hourly wages are up more than 10% from a year ago. And families, on average, have built up substantial savings from stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment benefits.

Many large companies are passing on the cost of higher pay to their customers, and in some cases, consumers are paying up rather than cutting back.

Fast food prices soared 7.1% in October from a year earlier, the government said Wednesday. That was the largest such increase on record, reflecting higher costs for beef and other foods as well as rapidly rising labor costs.

McDonald's boosted hourly pay 10% to 15% over the past year and is paying more for food and paper. The company said last month that it raised prices 6% in the July-September quarter from a year earlier. Yet company sales leapt 14% as virus restrictions eased.

Used car prices have rocketed more than 25% from a year ago. With automakers sharply slowing production because of parts shortages, prices for new cars have also risen for seven straight months. Furniture is more expensive. Grocery prices have climbed 5.4% in the past year, with the price of beef roasts leaping 25%. Bacon is up 20% from a year ago.

FALLOUT IN WASHINGTON

Republicans in Congress have blamed President Joe Biden's $1.9 trillion financial aid package, approved in March, for intensifying inflation. The additional stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment aid, they argue, drove demand beyond what the economy could produce.

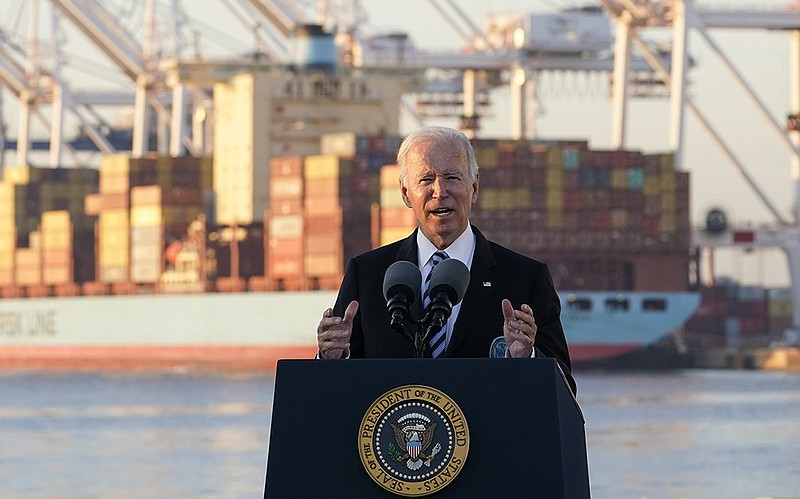

On Wednesday, Biden visited the port of Baltimore to highlight parts of the recently passed infrastructure package aimed at upgrading capacity at ports and, the administration says, helping unclog bottlenecks and ultimately reducing inflation.

"Inflation hurts Americans' pocketbooks, and reversing this trend is a top priority for me," Biden said.

Energy costs soared 4.8% from September to October, with gasoline, natural gas and heating oil surging for the same reason that many other commodities have grown more expensive. Demand has risen as Americans drive and fly more, but supplies haven't kept up. A gallon of gasoline, on average, was $3.42 nationwide Tuesday, according to AAA, up from $2.11 a year ago. The Energy Information Administration has forecast that Americans will spend 30% more this winter on natural gas and 43% more on heating oil.

Andy Husbands, 52, owns five Smoke Shop BBQ restaurants in Boston. Not only is Husbands scrambling to get ahold of every ingredient he needs to run his business -- he's also hard-pressed to find items at prices he can afford.

Wings that used to cost $84 per case now cost $157. To-go containers are in short supply, as are bottles used for storing liquor. Brisket that used to be $3.75 a pound is now a dollar more, meaning that the 150,000 pounds of brisket Husbands sells each year would cost him an extra $150,000.

Planning ahead has proved to be no match for the pandemic-era economy, with Husbands adding that prices can increase just over a weekend.

"It's insanity that prices can change on a truck when it's being delivered to you," Husbands said.

FOOD BANKS BUSY

Higher food prices are weighing on families that, in some cases, haven't sought handouts before, said Catherine D'Amato, who runs the Greater Boston Food Bank. During the height of covid, many of the people who came for help had been laid off or had their lives upended by the coronavirus. Now, even as parts of the economy show renewed strength, rising costs at the grocery store are forcing people into painful choices.

"Everything is tightening," said D'Amato, whose food bank is still feeding far more people than before the pandemic. "Are you going to use your resources to eat or pay for medicine? To buy clothes or eat? Are you going to pay rent or eat?"

Economists still expect inflation to slow once supply bottlenecks are cleared and Americans shift more of their consumption back to pre-pandemic norms. Consumers should then spend more on travel, entertainment and other services and less on goods such as cars, furniture and appliances. This would reduce pressure on supply chains.

But no one knows how long that might take. Higher inflation has persisted much longer than most economists had expected.

For months, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell had described inflation as "transitory," a short-term phenomenon linked to labor and supply shortages resulting from the speed with which the economy rebounded from the pandemic recession. But last week, Powell acknowledged that higher prices could last well into next summer.

The Fed chairman also announced that the central bank will start reducing the monthly bond purchases it began last year as an emergency measure to boost the economy. In September, Fed officials also forecast that they would raise the Fed's benchmark interest rate from its record-low level near zero by the end of next year -- much earlier than they had predicted a few months ago. Sharply higher inflation might accelerate that timetable. Investors expect at least two Fed rate increases next year.

Information for this article was contributed by Christopher Rugaber, Josh Boak, Dee-Ann Durbin, David McHugh and Diane Jeantet of The Associated Press; by Rachel Siegel, Andrew Van Dam, Laura Reiley and David Lynch of The Washington Post; and by Jeanna Smialek of The New York Times.