My recent column on the logistic difficulties the wine industry is facing, especially concerning holiday Champagne, seemed to strike a nerve with readers. I received several emails with myriad questions about sparkling wine, many of which I plan to answer as we get closer to New Year's Eve. Several of you, however, asked variations on the same thing: What's the difference between "brut," "extra brut" and "extra dry"?

Let me be clear: I love wine. But one of the things I hate most is the idiotic way we talk about sweetness in sparkling wines. Brut and extra dry have very strict definitions in France (which, thankfully, the rest of the world generally abides by), but they're actually just two levels in a scale that runs the gambit of sweetness from Death Valley dry to cloyingly sweet.

The final step in the Champagne manufacturing process is adding a small amount of sugar and wine (or sometimes grape must) called the "liqueur d'expedition" or "dosage." The sweet dosage balances out the sparkling wine's extreme acidity, bringing it, ideally, into a perfect, crystalline balance. As the wine has already finished fermenting, any sugar in the dosage will remain intact in the wine. Those in the wine business typically refer to this sugar as "RS" for "residual sugar." Keep in mind that a bottle of Champagne with a little residual sugar won't necessarily taste sweet. The wine's high acid levels typically mean that only the most trained palates can detect the sugar at most levels.

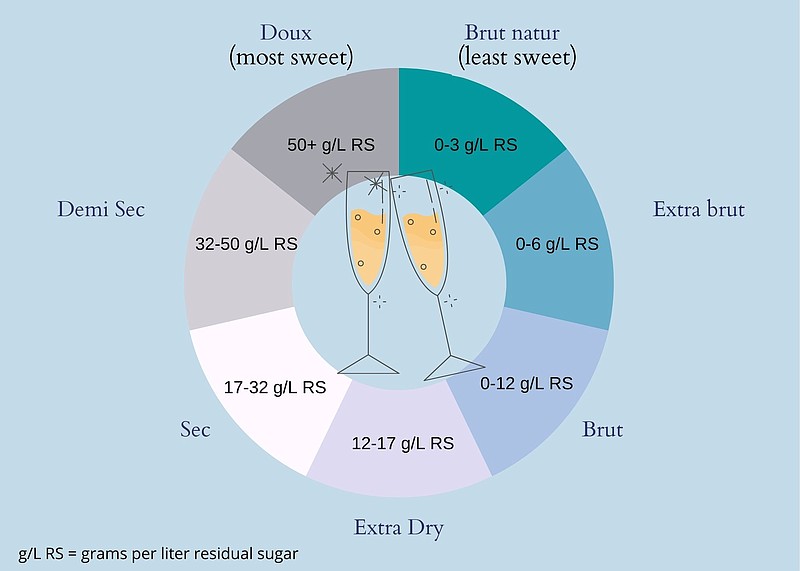

Champagnes produced with zero to three grams per liter of residual sugar (g/L RS) are labeled with the terms "brut nature," "pas dose," or "dosage zero" on their front label. Though rare in Arkansas, this style is among my favorites. These wines are brash and heroic and offer a level of barely controlled energy that I always find incredibly fun to drink.

Wines labeled as "extra brut" will have between zero and six grams g/L RS, brut wines can have anywhere from zero to 12 g/L RS, while extra dry wines can have 12-17 g/L RS. So, extra brut is dryer than brut, but extra dry is sweeter than brut and extra brut. Clear as mud, right?

The vast majority of Champagne you'll find on shelves will fall into the brut category, though sometimes it's worth checking your bottle's back label for more detail. Some producers have begun labeling the amount of RS in the wines. If you can find two wines at the opposite end of the brut spectrum, they'll make for an interesting comparison. At these low levels, the wine won't taste sweet, per se, just a little richer and rounder in your mouth.

From here, as the wines get sweeter, they also become rarer. "Sec" denotes a wine with 17-32 g/L RS, and "demi-sec" refers to wines ranging from 32-50 g/L RS. These wines are always fun to drink. I like serving them at the end of the meal, especially when dessert skews toward the savory side. (They're also perfect with a cheese plate.) I suggest finding a bottle of Champagne Billecart-Salmon Demi-Sec ($68) or Champagne Laurent-Perrier Harmony Demi-Sec ($54). Wines with 50 g/L RS or more are labeled doux.

I know any talk of sweetness in wine can turn people away, but keep this comparison in mind: Coca Cola clocks in at around 108 g/L RS, still more than twice the sugar level of a "sweet" demi-sec Champagne.

As always, you can see what I'm drinking on Instagram at @sethebarlow and send your wine questions and quibbles to sethebarlowwine@gmail.com