Redistricting is just getting started around the country, but the first maps released suggest a coming decade of even more deeply entrenched partisanship for Congress.

Most House lawmakers already represent solidly partisan constituencies. Every two years, party control is determined by the outcome of only a few dozen seats. And next year, Republicans need to flip only a handful of seats to wrest power away from Democrats.

Of the country's 435 congressional districts, former President Donald Trump or current President Joe Biden won just 50 of them by 5 percentage points or less. Those swing districts could be reduced by at least a third after redistricting, experts estimate.

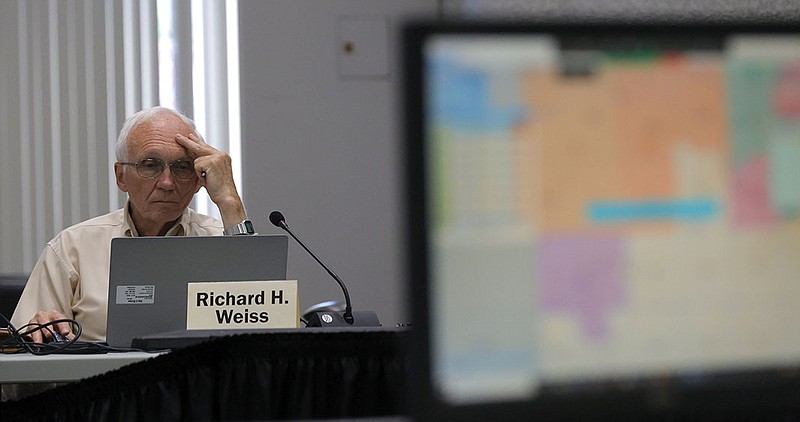

On Thursday, Republicans in Arkansas finalized a new map that sliced Pulaski County into three congressional districts, dividing voters in the most populous and racially diverse part of the state. The state's 2nd Congressional District, which would have been a stretch but not impossible for a Democrat to win under the current lines, is now seen as safe for a Republican.

Nick Cartwright, a Democrat running to take on incumbent Republican Rep. French Hill in that district, said he believes the new lines were drawn to create a GOP firewall.

"This was the most competitive district in the state by far; there's no doubt in my mind that [Hill] spoke to Republican buddies in the Legislature about how to make it easier for him," Cartwright said. "It's unfortunate Republicans want to choose power over fairness, but I don't think it's a surprise either."

Hill was not available for an interview but told a local radio station on Thursday that there had been "a lot of noise" about the redistricting.

"Look, my job is to represent that district, and I will do my best every day to represent the district drawn by the Legislature," he said. "I leave it in their hands as how to fine-tune it and get political acceptance on it."

In Texas, a proposed Republican reworking of U.S. House districts would reduce the state's 12 competitive districts to one. In Oregon, the approved Democratic map shored up two competitive seats, making them more solidly blue.

In Indiana, Republicans eliminated the state's only competitive seat by shifting it from a district Trump won by 2 percentage points to one he would have won by 16.

"There are really only about three dozen truly competitive seats anyway, and partisans have realized in these polarized times the best way to flip a district is to gerrymander it after the census," said David Daley, a senior fellow for FairVote, a nonpartisan voting-rights advocacy organization, and author of two books on modern redistricting.

"Now, partisans are coming back for more."

Ahead of the 2022 contests, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee had listed two Texas districts currently held by Republicans as targets to flip in 2022, but the proposed new map would push them out of reach.

The 23rd District, which stretches along the border from San Antonio to El Paso, would go from a district Trump won by less than 2 percentage points to one that he won by 7. The 24th District, located in northern Dallas, would turn from one Biden won by 5 points to one Trump would have won by 12.

Democrats had also hoped to target Indiana's lone competitive district, which will now become solidly Republican.

For its part, the National Republican Congressional Committee included both competitive Oregon districts, held by Democrats, on its target list. The new map makes both much safer for Democrats.

Oregon is the only state where redistricting is controlled by Democrats that gained a seat because of population growth. The state's redistricting chairwoman, Democratic state Rep. Andrea Salinas, announced last week that she may run for the new seat -- a deep-blue district south of Portland that Biden would have won by double digits.

Rep. Christine Drazan, the Oregon state assembly GOP leader who sat on the Legislature's redistricting committee, pointed to Salinas' move as evidence of partisan self-interest afoot during redistricting.

"Politicians should not be drawing political boundaries, no matter who they are," she said in an interview.

POLITICAL POLARIZATION

The bitter polarization in American politics relies on many factors, but many critics of Washington's persistent gridlock point to partisan gerrymandering as a leading reason that lawmakers in Congress have little incentive to compromise -- and indeed, are discouraged from it.

"If you're representing a district where you have to listen to both sides, you hear both points of view, and then you go to Washington and you find most everyone else comes from a district where they only hear one viewpoint," said former Congressman Jason Altmire, who lost his reelection bid in a 2012 Democratic primary in Pennsylvania after redistricting merged his district with one held by another Democratic incumbent.

The primary winner, former Congressman Mark Critz, lost in the general election to a Republican who was aided by the narrowly red district. Altmire, a moderate Democrat from the Pittsburgh suburbs, was one of many casualties of redistricting in 2011, when Republican officials in charge of the process in most of the nation's traditional battleground states redrew boundaries to increase their share of the seats.

Before 2011, at least six congressional districts in Ohio had swung back and forth between Democrats and Republicans over the previous decade.

When Barack Obama won Ohio in the 2008 presidential election, Democrats won 10 of the state's 18 U.S. House seats. Four years later, after Republicans redrew the lines to their advantage, Obama again won the state, but Democrats won only four seats.

Democrats have not flipped a single GOP seat in the past decade.

Ohio, which lost two seats a decade ago, is losing another one in the current mapmaking. Republicans, who control state government, have not yet released new congressional boundaries, but Democrats are bracing for the loss to come at their expense.

That would reduce their representation to just three of 15 seats in a state in which Biden received more than 45% of the vote.

Nationally, Democrats lost the House in the 2010 Tea Party rout before redistricting, but new maps in 2012 made it much harder to win it back. In the next three congressional elections, Republicans had a net benefit of 16 to 17 seats because of partisan gerrymandering, according to a 2017 analysis of election results by the Brennan Center for Justice.

The GOP hold on the House lasted until 2018, when Democrats won back the majority largely because of a repudiation of Trump among suburban voters, boosted by netting three new Pennsylvania seats after the state Supreme Court ordered the state to redraw its gerrymandered map.

"The design is to bake in results. They are defensive gerrymanders. ... It's very much about creating safe districts," said Michael Li, redistricting expert at the Brennan Center. "If you have competitive seats, it's because a commission or a court drew them."

Democrats in Maryland may gut the only Republican-held seat in that state, creating an 8-0 Democratic delegation. And in states like North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida and Utah where the populations are becoming more diverse and Democratic, particularly in the suburbs, Republicans in charge are expected to carve up the maps to heed off any potential Democratic gains.

"These are not short-term seat maximization gerrymanders; they are designed to build a wall around demographic change, designed with an eye on what the state will look like in 2026, 2030," Daley said.

The erasure of competitive districts also means the number of lawmakers willing to buck their party and vote with the other side will continue to diminish.

Two possible casualties of redistricting in next year's election are Reps. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., and John Katko, R-N.Y., two of the 10 Republicans who joined Democrats to vote to impeach Trump over the former president's role in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

In Illinois, which is losing a congressional seat, Democrats in control there are expected to scrap Kinzinger's district and force him into a primary with another Republican incumbent.

Kinzinger was not available for an interview, but in a written statement he said state Democrats were a "prime example" of redistricting partisanship.

"Right now, Democrats in Illinois are picking their own voters behind closed doors -- using their power to make sure their party stays in power. We see this on both sides of the aisle, and this adherence to party politics will only further the divide we have in this country," he said. "Tribalism is absolutely ruining politics, and it's leaving many to feel politically homeless as a result."

Katko, who already represents a district that tilts Democratic, is expected to find his Upstate New York district become even bluer.

Katko was not available for an interview.

Other Republicans who voted to impeach Trump, like 18-term moderate Rep. Fred Upton of Michigan, may find themselves in redder, less familiar territory as redistricting makes them more vulnerable to primary challengers who will then have a huge edge in the general election.

"If you draw a district that's safe, the party no longer cares about recruiting a broadly appealing candidate," said David Wasserman, a veteran analyst of election data for the Cook Political Report. "This is a vicious cycle in that the decline of competitive seats leads to a more extreme and dysfunctional Congress."

Information for the article was contributed by Kevin Uhrmacher, Adrian Blanco and Harry Stevens of The Washington Post.