After 16 months of trying to get answers about her brother's death, Christine McAuliffe filed a $7 million claim Tuesday against the Arkansas Department of Human Services, continuing a push for stronger oversight in facilities for those with intellectual disabilities.

David Cains was a 13-year resident at the state-run Booneville Human Development Center, where he died on June 13, 2020, after having a medical emergency while being physically restrained by center staff members.

In a complaint filed Tuesday with the Arkansas Claims Commission, Cains' family accused the facility of negligence surrounding its restraint practices.

"Despite knowing, and even memorializing in its internal documents, that physical restraints 'dramatically' increased the risk of injury to disabled patients, [the center] did nothing to enforce a policy reflective of this dramatic risk," the complaint reads. "In fact, according to [the Booneville facility's] records, staff used physical restraints on David Cains at least 16 times in the one year preceding his death."

When asked about the incident and the recent claim, Human Services Department spokesman Gavin Lesnick said agency officials do not comment on pending litigation.

Cains' death in Booneville was the latest in a line of incidents at the facility that have been flagged by watchdogs.

In January 2015, Disability Rights Arkansas released a report expressing concerns regarding both the physical conditions and the high number of restraints at the facility, recommending the closure of the Booneville center.

The advocacy nonprofit organization concluded "that the restraint practices at Booneville HDC are both contrary to currently recognized best practices regarding restraints and puts residents and staff at risk of physical and emotional harm," according to a 2016 report.

The fallout around Cains' death comes as the state explores changes to restraint practices at the Booneville facility and others like it. However, the effort suffered a setback in August when the consultant set to make recommendations for the residential facilities bowed out because of a conflict with his employer. State officials have said the Human Services Department remains committed to the effort.

Physical, chemical and "mechanical" restraints are in use in Arkansas' five human development centers, which house more than 800 people with disabilities and health issues across the state.

"Mechanical" restraints are devices such as restraint chairs, wrist wraps and a padded board with straps, called a papoose board. Chemical restraints are medications.

Cains was 42 at the time of his death, but testing indicated that his vocabulary, and likely his overall intellectual functioning, was similar to that of a 4- to 6-year-old child, the family and its attorney Josh Gillispie said.

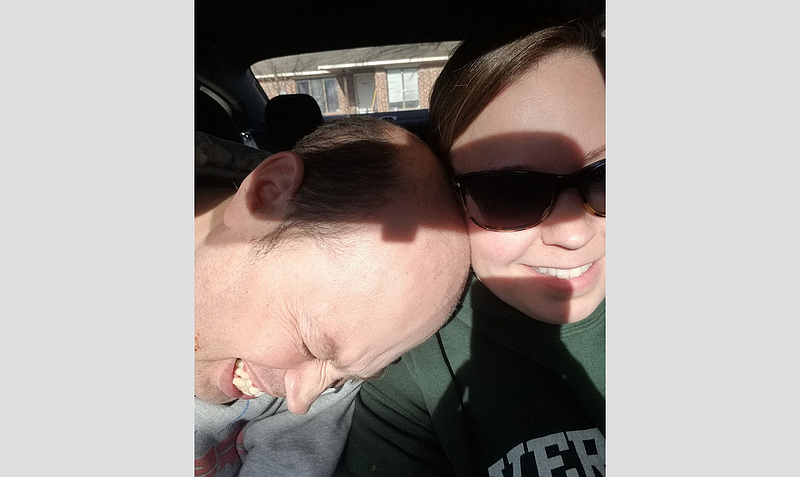

"Davie," as his family called him, talked nonstop, McAuliffe said, "and that's not an exaggeration."

He was happy, outgoing and quick-witted, said his mother, Charlene Robinson. Despite being a big Razorback fan himself, he enjoyed riling other fans with smack talk.

"I didn't feel like our sibling relationship was different because of his disability," McAuliffe said. "We were best friends as kids, and that never changed. We were very close."

Cains spent time with his family regularly, often watching his favorite shows, such as "M*ASH" and "The Dukes of Hazzard," or listening to the Monkees. Covid-19 protocols made visiting more difficult, Robinson said.

Robinson said she was sitting with her dog while watching TV last year when the phone rang. She was told that Cains had choked at lunch around 11:30 a.m. and had been taken to Mercy Hospital Booneville.

He was declared dead at 12:21 p.m., according to the DHS Final Synopsis.

Nine days later, three days after Cains' burial, his family received the investigative determination in the mail and learned -- to their surprise -- that the staff had used physical restraint holds during the incident.

If they had known, the family would have requested an autopsy, McAuliffe said.

A Logan County emergency medical services record doesn't mention restraints in a five-paragraph narrative, and a previously reported coroner's record also repeats the description that Cains "was eating lunch."

In written responses to questions previously asked by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Lesnick said officials "cannot speak to or verify what information was provided" to the health entities, but they do not believe there is a discrepancy with the physician's and coroner's reports. The agency "cannot advise on the specifics of how David aspirated," but he'd recently eaten, Lesnick wrote.

Cains was held in personal restraint after he physically attacked a staff member, the Human Services Department's report of the incident states. When he stopped breathing, medical staffers were called. They responded in one or two minutes, then EMS was called.

A state internal investigation found that three staff members who restrained Cains "conducted themselves in an appropriate manner and immediately responded" to him, according to an incident report shared with a reporter. All three were cleared to return to work the following week.

An independent investigation by Disability Rights Arkansas in October 2020 found that Cains aspirated and choked to death after being taken to the ground in a physical restraint performed by three staff members. It found that they pinned him to the ground -- one held his arms, one his ankles and the other his head -- while he threw up and choked, only stopping when he defecated, turned purple and stopped breathing.

Cains suffered from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which occurs when stomach acid frequently flows back into the tube connecting the mouth and stomach, according to the Mayo Clinic. He was on physician-ordered precautions to remain upright for an hour after meals, according to the family's Tuesday complaint.

Subjecting someone with GERD to a physical restraint shortly after a meal increases the risk of death from suffocation because of a higher probability of throwing up, the complaint states.

The center has a policy that prevents non-medical staffers from dialing 911 in response to a medical emergency. The Logan County coroner's report states that 911 wasn't called until 11:37 a.m. At least four minutes elapsed from the time the staff noticed he was not breathing to the time 911 was called, the family's claim said.

The Booneville center is the only such site that does not have cameras. Some were bought in June, but construction contracts for a fiber-optic upgrade needed to run the devices is in the bidding and procurement process, Lesnick said. He added on Tuesday that the agency is working through the process, and the cameras have not yet been installed.

McAuliffe said that in the days after her older brother's death, she grew confused by the little and differing information she received.

This was not the only time restraints were used on Cains, which McAuliffe had voiced concerns about to his case manager before, but she said she felt that lines of communication had always seemed open in the past.

Cains was happy and enjoyed living at the center, where he worked an on-site job and attended life-skills classes. He would say after time together that he "had to get back to my friends," Robinson said.

"After he passed, I got tons of messages from people who had been around him over the years at Booneville," McAuliffe said. "That they were excited to go to work because my brother always had a smile, he was always laughing."

The family had no idea about the center's history with restraints until after Cains' death when McAuliffe began digging and researching.

In February 2015, a similar restraining incident at the center resulted in a woman with known seizure issues choking to death. McAuliffe said residents' families should have been notified of such incidents.

"It's just the transparency. How can anyone trust the state of Arkansas if they don't do the right thing when something goes wrong or someone screws up?" she said. "The worst-case scenario is what happened to my brother, and the response by the state is just disgusting.

"If this can happen to my brother, who had a family that was so involved, and their response to the worst-case scenario is no response other than 'I don't see anything that was done wrong,' what is happening day-to-day, especially with restraints and other things that don't lead to death?"

The Arkansas Claims Commission hears and adjudicates claims against the state. The commission is an alternative to filing a lawsuit against the state, which under a provision in the Arkansas Constitution can't "be made a defendant in any of her courts."

Claims Commission awards exceeding $15,000 must be approved by the General Assembly.

Cains' family members said they want acknowledgement of wrongdoing and policy changes to protect residents of these facilities.

Gillispie said he came to the figure for the claim with the idea that if what happened to Cains could not spark change, then perhaps the loss of $7 million would.