There was no chance Van Morrison was going to agree to be vaccinated to perform at the Santa Barbara Bowl. For more than a year, the cantankerous 76-year-old Northern Irish rocker had been bashing government efforts to control the coronavirus, releasing songs with such titles as "Born to Be Free" and "No More Lockdown."

That put AEG Presents in a pickle. The concert promoter, which has been trying to revive the shuttered concert market, decided that, starting Oct. 1, it would require everyone to be vaccinated at venues it owns, on- and offstage. Would AEG actually tell the "Moondance" singer-songwriter that he couldn't take the stage that Sunday, Oct. 3, at the 4,562-seat venue in coastal California? Ultimately, no, as Morrison agreed to at least be tested.

"We're in the relationship business with the artist, and ultimately we didn't feel we could draw the line," says Rick Mueller, the president of AEG Presents North America. "But they've been respectful and not argumentative. And (Morrison) willingly said he'd come with a clean test within 72 hours."

This is life in the purgatory of a pandemic that went away, returned and has now settled in for an unwelcome encore. For some performers, who got a renewed taste for crowds as theaters, symphony halls and clubs reopened in early summer, it's hard to stop the show. But the aggressive delta variant has led some headliners, including Garth Brooks and Stevie Nicks, to cancel tours. Still others, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra, have chosen to postpone glitzy galas and focus on making sure regular programming can go on. And for those taking the stage this fall, a sobering philosophy has emerged: We can't beat covid, so we've got to learn to coexist with it.

"It's not easy," says Dave Grohl, whose Foo Fighters have played several shows since a celebrated June return gig at Madison Square Garden. "You wake up every day, cross your fingers that they'll open a door, turn on the lights and we'll have a rock show. It's not guaranteed."

The Foos' camp is vaccinated and they're playing venues where vaccinations or tests are required. Still, in July, the band had to cancel a big show at the Los Angeles Forum after someone in its organization tested positive for the virus. That has happened to other groups as well, including KISS and the Zac Brown Band. And on Sept. 29, Disney's "Aladdin" had to cancel performances after coronavirus cases were found within the production. Performances resumed a day later, but then had to be stopped for two weeks as more cases cropped up.

But on Broadway, this remains the exception. The difference between this and last year is dramatic, says producer Matt Ross, whose "Pass Over" became the first play to return to Broadway, in early August.

"The decision to pause last year, to pause everything, was a life-and-death decision," Ross says. "What's happened since then is we've learned a lot more about the science, we've learned a lot more about protections, our testing has come a long way and we've got vaccines. Which are not 100%, but I would also say no manageable risk is 100%. We all make choices about manageable risks. We do that every time we get in a car or get in an airplane or swim in the ocean or eat raw seafood."

GEOGRAPHICAL ADVANTAGE

Ross also says he is grateful that his productions are in New York, where audience members and anyone performing indoors, even athletes, must be vaccinated. That's also the case in many venues in Boston, where the Boston Symphony Orchestra opened its season Sept. 30 before a crowd of 1,825, down only slightly from past opening nights.

It was a special night, and Gail Samuel, the orchestra's new president and chief executive, addressed the audience before the performance began. Behind her, some musicians wore masks, some didn't. All were vaccinated.

"I am generally a person who is a real believer in the ability of music to speak for itself," she told the crowd. "However, tonight, 568 days since a live audience gathered in this hall to hear this great orchestra, it feels like it's important to give voice to some of what we are all feeling. I want to say thank you to all of you ... for the incredible unprecedented support you showed this organization over the last 18 months."

Samuel said that out of caution, the orchestra decided to postpone its annual fundraising gala until the spring. She also said that while ticket sales are down about 30% from a typical season, she expects people to return once they see that it is safe to go to Symphony Hall.

"The focus has been on keeping people safe and following the science and the guidance," Samuel says, "but another overarching principle is (that) gathering is important."

In this new normal, the difference between large touring organizations and small independent performers has become even more obvious. Major rock bands have covid compliance officers on board and can keep from interacting with crowds. Smaller groups and solo performers need to rely on themselves and try to bubble up as best they can.

SMALL-ACT WOES

That goes even for Margo Price, a critically acclaimed country singer who has topped the charts in England and appeared on "Saturday Night Live."

Recently, Price had a gig in Kentucky, four hours from her home in Nashville. But no one could find a bus driver who had been vaccinated — a requirement in her camp. So without a ride, Price rented a couple of box trucks for her gear and threw her guitars in the back of her pickup. She drove herself to the Railbird Festival.

"We had covid," Price says. "My husband almost died. And we lost John Prine. It's a very serious thing. We don't want to make this a big political statement. We want to take care of our families."

Jazz guitarist Pat Metheny, who recently started touring to support his new album, "Side-Eye NYC (V1.IV)," is vaccinated, as are his band and crew.

"But we've got one tour bus," he says. "There will be 12 of us, including the driver. Everyone has to be vaccinated. Although we do have one crew member who was vaccinated and got a breakthrough case a few weeks ago and was under the weather a few days. Honestly, that's the big question: What do we do if that happens? I really don't know."

UP AGAINST GOVERNORS

There are also the geographic challenges to contend with. In a handful of states, governors and legislators have been blocking vaccine mandates, which arts presenters and performers say makes it difficult to reassure potential audience members. The Houston Grand Opera, after consulting with lawyers and surveying patrons, will require masks at performances when it opens its season this month. Khori Dastoor, the company's general director, says she has been frustrated by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott's push to ban vaccine mandates.

"I can only say that I haven't been in the state long enough to know why the governor is doing what he's doing," Dastoor says. "My responsibility is to my patrons. They are not only smart, but they're feeling more vulnerable to this virus than perhaps a younger population. Many of them have been the first to lock into their homes and the last to come out."

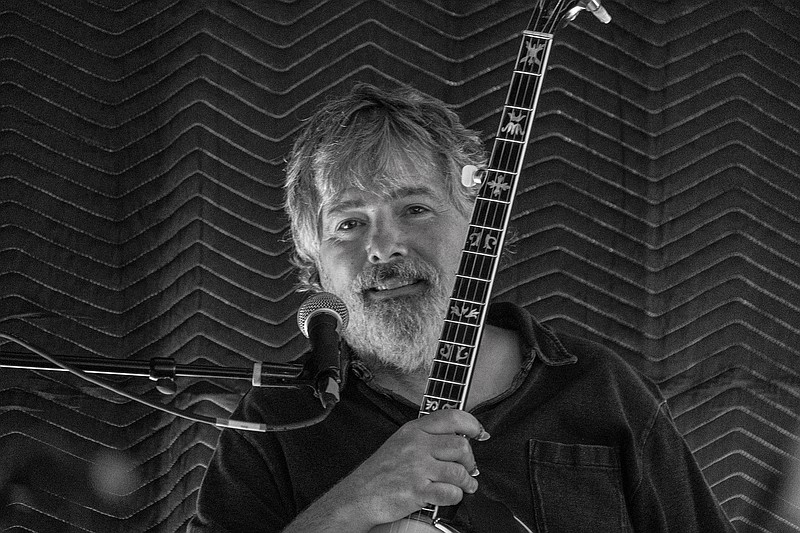

Bela Fleck, the Grammy-winning banjo player, will play only where vaccinations and masks are required. He and his wife, musician Abigail Washburn, have two children who aren't old enough to be vaccinated. They have postponed an Oct. 24 date in Athens, Ga., because of Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp's opposition to mask and vaccine mandates.

"There were some people who came in and wrote me messages and said, 'I'm not your fan anymore and I don't like you for doing this,'" Fleck says. "And I wrote them back and said, 'I'd rather have you be mad than going to my show and getting sick.'"