In English departments the most serious competition is for the role of straight man. — Richard Russo, "Straight Man," 1997

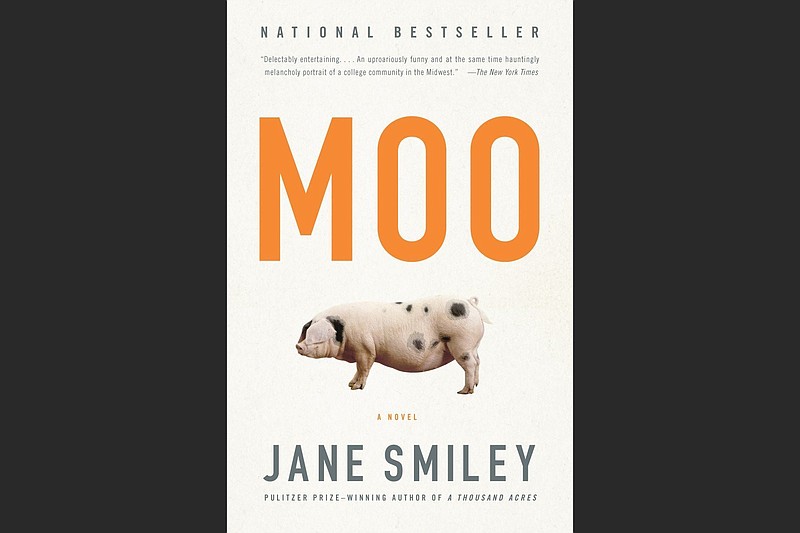

In Jane Smiley's 1995 novel,"Moo," there is an 18-month old snowy-white, 700-pound Landrace boar — "as big as a Volkswagen Beetle but much faster" — residing in an abandoned building, Old Meats, in the middle of the campus of a state university somewhere in the Midwest, a land-grant institution known colloquially as "Moo U."

The pig's name is Earl Butz — after the secretary of agriculture who served under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford and is best remembered for the racist joke that ended his career. The human Earl Butz was known for advising farmers to "Get big or get out," and that slogan is taped to the wall in the hog's quarters.

A sophomore work-study student named Bob Carlson cares for the hog, whose existence is known to only a few and whose only purpose is to eat and grow as large as possible. Bob has been sworn to secrecy; he can't even tell his father about Earl Butz, who is at the center of an experiment by Dr. Bo Jones. Dr. Jones, having noticed that since few hogs live long enough to die of natural causes, is determined to allow Earl Butz "to eat at will for all of his natural life span" in an effort to find out "something about hog."

It doesn't spoil anything to mention that Earl Butz doesn't make it to the end of his natural life; Dr. Jones disappears while on a trip to Kyrgyzstan to study wild boars and Old Meats is demolished to make way for a McDonald's. Earl Butz escapes the building, but dies of a heart attack after frantically racing across the campus.

This is the one section of Smiley's gentle satire that bites deep. It's not hard to see the symbolism: Old Meats is "an abattoir at the dead center of campus." Earl Butz is "the secret hog at the center of the university," the very embodiment of Moo U., an anonymous cow-town school in the middle of the country voraciously consuming dollars and resources. It attracts students — "consumers" — with promises it cannot keep and encourages its faculty to develop ethically dubious relationships with would-be donors from the private sector.

Late in the book, the school's provost puts it this way:

"Over the years ... everyone around the university had given free rein to his or her desires, and the institution had, with a fine trembling responsiveness, answered, 'Why not?' It had become, more than anything, a vast network of interlocking wishes, some of them modest, some of them impossible, many of them conflicting, many of them complementary.

''[The provost] himself resisted neither the wishes nor those who offered funds to pay for them. The most that he could say for himself was that, from time to time, he had felt obscurely uneasy."

It's interesting that the publication of "Moo" didn't seem to cause any trouble for Smiley, who was a member of the faculty at Iowa State University for 15 years and is reportedly still beloved by the university community. But academics, like journalists and the celebrated denizens of Hollywood, tend to run to narcissism. Any attention, even negative attention, is to them as molasses and corn and peanuts were to Earl Butz.

When Richard Russo published his campus novel "Straight Man" in 1997, he expected a backlash from academia. Instead he was surprised to encounter professors and graduate students turning up at his book readings wearing fake noses and glasses in tribute to the book's pivotal scene, where a similarly disguised English professor goes before a local news channel camera crew, holds up a goose by its neck and threatens to kill "a duck a day" until his department receives full funding.

"Straight Man," a genuinely funny and deeply serious work, is set at fictional West Central Pennsylvania State University, in the made-up town of Railton. Hank Devereaux, Russo's protagonist, wrote a well-reviewed but poor-selling novel ("Off the Road") 20 years before, and has settled into a sort of comfortable mediocrity, taking pleasure in undermining the vanities of his more pompous colleagues — who include a feminist critical theorist known as "Orshee" for his reflexive correction of anyone who uses a masculine pronoun to refer to subjects whose gender is unclear or variable.

In "Straight Man," Hank has just been named temporary chairman of the department, a dubious honor he suspects he'll be stuck with forever because any promotion at a directional school like WCPSU is akin to winning a "s---eating contest."

Such honors hold no currency in the larger academic world, and only make it harder for the recipient to leave the school, as they would have to give up "tenure or rank or salary, or some combination of all three" in order to move to a better situation.

As chair, Hank has to deal with rumors of staff cutbacks and the paranoia of his colleagues who are sure he's prepared "a list" of recommended sackings. He has not, but provocateur that he is, he's not willing to tell them that. After all, some — maybe most of them — deserve to be fired. And maybe it would be the best thing for them; Hank's not sure he'd mind if he was fired.

That a lot has been written about Netflix's recently released limited series, "The Chair," is probably because a lot of people who write about pop culture for magazines and websites actually support themselves by giving lectures, grading papers and negotiating the bureaucratic maze that is academe.

It's exciting and flattering to see yourself and your ilk represented on the screen. It's an occasion for an easy piece on what the show gets right and wrong about your world.

I'm not sure how popular "The Chair" actually is — Netflix offers us a list of 10 most popular shows, and as I write this "the Chair" comes in at No. 8, behind "Family Reunion" and just ahead of "Gabby's Dollhouse," neither of which I've seen any long-form think pieces about — but it is an interesting show that people are chattering about now that rewards thought. Though it presents as a typical workplace comedy (or more accurately, "dramedy," a dangerous tone to try to sustain) by feeling poignant and elegiac, it is actually a lament for the death of the life of the mind.

It's about a college — and a culture — in the midst of an existential crisis: How long can we go on pretending that anyone cares about anything more than what the human Earl Butz infamously suggested: creature comforts like comfortable shoes and warm toilet seats?

In the show, which was created by actor/writer Amanda Peet and academic/screenwriter Annie Julia Wyman, Sandra Oh plays Ji-Yoon Kim, the first woman and the first person of color to become the chairperson of the English department at Pembroke University, a quite Ivy League-y liberal arts school located in some stereotypical college town, probably somewhere in the northeast.

Her accomplishment is compromised by the feeling that she has "arrived at the party after last call," as on her first day in the role the college dean (David Morse) hands her the kind of list that Russo's Hank Devereaux never had.

"These folks have the highest salaries and lowest enrollments in your department," he tells her. "Before I bring out the stick, maybe you could use your persuasive powers as chair."

My brushes with academe have been relatively minor, but even I understand the absurdity of this request. Tenured faculty can't be fired except for cause, and pressuring them to resign is illegal. There's little Ji-Yoon could do even if she wanted to comply with the dean's request.

But there's another wrinkle to the scene; we're allowed to glimpse the salaries on the list. The highest paid professor is Elliot Rentz (Bob Balaban), a Melville expert who's been — we're led to assume — working at the university for 40 years.

He's being paid a respectable but hardly exorbitant $132,000 a year. (The average salary for a full professor at a private institution is a little less than $177,000 per year, but that's for all disciplines and includes public and private institutions. According to a salary.com calculator, an English professor with 20 years' experience working in Burlington, Vt. (which seemed a reasonable analog for the setting of "The Chair") could expect to make $111,417.

The cost of tuition at a private liberal arts college is approximately $24,000 a year, and Pembroke is presented as a snotty little place. I'd bet its tuition is probably closer to the $75,950 a year Bennington College charges its students, or at least the $58,504 that Oberlin charges or the $47,600 that Hendrix College charges than it is Calumet College of Saint Joseph ($13,290), Tougaloo College ($12,967) or Harding University ($20,735). And while you might be able to hire five or six adjuncts for the price of one Rentz, what about the educational product you're offering?

Ji-Yoon attempts to remediate the situation by merging Rentz' under-attended class with the popular Sex and the Novel taught by rising star Yasmin "Yaz" McKay (Nana Mensah). Her thinking is that it will help Yaz by giving her quality time with Rentz, who serves as the chairman of the tenure committee, while avoiding the optics of having three or four students spread out in Rentz' classroom. But Rentz proceeds to treat Yaz as a teaching assistant, requiring her to hand out study sheets as he drones on from the lectern.

Yaz is the only other nonwhite member of the English faculty, and Ji-Yoon desperately wants to keep her from moving to a more prestigious university because she's popular with students and a good scholar. Ji-Yoon wants more diversity, and, as a carrot, announces that she'll be delivering a prestigious lecture. She works to get the dean to fast-track her tenure.

It's clear digital-savvy Yaz knows how to connect with an audience, incorporating social media posts and rap lyrics into her lectures in a way that gives her old white classicist colleagues pause. And the show is willing to subtly interrogate the ultimate utility of this kind of performative relevance — none of the characters, Yaz included, gets off scot-free.

But in the end, "The Chair" is a half-hour Netflix series. That means it has to at least nod to the conventions of the form. Ji-Yoon's chief project is not Yaz but Bill Dobson (Jay Duplass), a recently widowed former superstar author/professor who bears a more than passing resemblance to Grady Tripp of Michael Chabon's 1995 novel "Wonder Boys," based on novelist Chuck Kinder. (Tripp was played with some finesse by Michael Douglas in the 2000 film.)

Bill is grieving his wife and crushing on Ji-Yoon when he's canceled after — in an extemporaneous lecture he delivers after showing up for his class completely unprepared — making a stupid Nazi joke that's willfully misconstrued by a woke student population.

It's a moment that recalls the blunder made by professor Coleman Silk in Philip Roth's 2000 novel "The Human Stain," only Silk's comment was innocent while Bill's is just stupid.

Still, Bill and the students he engages — in an impromptu "town hall" he calls on the college quad to discuss the incident — seem to be making genuine progress toward understanding when, in a ham-handed move that has nothing to do with the meeting itself but with a perceived financial opportunity — the dean calls the police in to disperse the crowd.

You'd think it would be easier to deal with the problem that Joan (wonderful Holland Taylor), the flinty Chaucerian who sees no reason to read her brutal student evaluations, brings her. By some bureaucratic quirk, probably a simple mistake, Joan has been assigned an office in the basement of the gym. Plus she has no Wi-Fi.

More immediate concerns keep Ji-Yoon from attending the meeting in the Title IX office where Joan goes to file a complaint. But what could possibly go wrong?

Ultimately Ji-Yoon is forced to renege on her promise to have Yaz deliver the lecture because a donor has come up with the bright idea of having David Duchovny — the "X Files" and "Californication" actor — give it. And maybe Duchovny could teach a course as a visiting scholar?

There's something delicious in Duchovny playing himself in this situation; I haven't read any of his books but he is, as they say in the show, "a New York Times best-selling author," and is (still) working toward a Ph.D. in English literature at Yale. He wrote a 160-page paper titled "The Schizophrenic Critique of Pure Reason in Beckett's Early Novels" as his senior thesis at Princeton. His first novel, "Holy Cow: A Modern Day Dairy Tale," was published in 2015.

I tried to track down a copy of Duchovny's senior thesis for this story but couldn't negotiate the Princeton site. In "The Chair," Ji-Yoon finds and reads it. When she meets Duchovny she tells him she found it dated.

"A lot has happened in the last 30 years," she says. "Like affect theory, eco-criticism, digital humanities, new materialism, book history, developments in gender studies, in critical race theory."

For all I know it's another "Moo."

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com