[Editor's note: After decades of involuntary shaking caused by essential tremor, freelancer Jerry Butler underwent deep brain stimulation at UAMS Medical Center. This is Part 2 appeared Sept. 27, and Part 3 appeared Oct. 11, 2021. See arkansasonline.com/927part2 and arkansasonline.com/927part3]

■ ■ ■

Tremors in my right hand began interfering with my daily activities more than 30 years ago. They increased in severity at a rate of about 3% a year. Like the burden of compound interest upon a homeowner, they became so profound that tremors have restricted my eating, my leisure, my work, my comfort in social situations and the kind of life I choose to live.

Fortunately, there is a remarkable but daunting alternative.

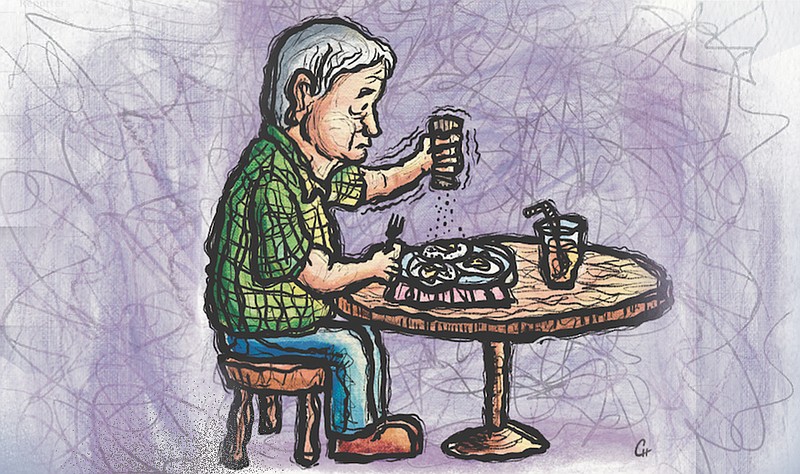

I've always liked purple-hulled peas. Recently, I've taken to eating them with honey. I don't like the honey, but it's the only way to keep the peas on the fork.

I like fried eggs for breakfast. Cutting them up and eating them each Wednesday with the ORFs (Old Retired ... let's say Folks) at Megan's Diner is an ordeal. I've resorted to eating only an English muffin, with my left hand. When I complained, another of the codgers I eat with said, "Yeah, I can see you are having a bit of a problem with eating, but you are doing a hell of a good job with the salt and pepper shakers."

I like to fish. My tremors got so bad that folks told me I would have to stop fishing because I could no longer tie a hook. A fellow can do something if he wants to bad enough. So, I still fish. I still manage to tie a hook.

Then they told me I would never be able to clean the fish I caught — turns out they were right.

Everyday tasks — texting on a small cellphone, inserting a key in a lock — are virtually impossible for me. Especially if I am in a hurry, upset or cold; under those conditions my trembling is worse.

In 1952, my fifth-grade teacher nominated me for the Pulaski County Penmanship Award. When I wrote my first book in 1972, I wrote each word in remarkably attractive cursive script on yellow tablets. A typist took those tablets, and after only a little clarification, mailed them to my publisher. By 1992, it took a typist longer to decipher my penmanship than it did to type my manuscript.

In 2002, I stopped writing in my personal journal because even I couldn't read it. I can pursue my avocation as a freelance writer only because of computers with large keyboards, intuitive Microsoft word-processing programs, my left-hand-only hunt-and-peck system and hard-headed stubbornness.

If the state of Arkansas applied a rigorously verifiable signature check to validate a ballot for president of the United States, I would be disenfranchised. My signature does not even look like the signature I made last week, and surely not like the one on my voter registration card.

I have not been able to legibly fill out a check in five years.

I am a licensed master electrician. It is dangerous for anyone with profound tremors to use a screwdriver in an energized circuit panel after the cover is removed. (That is, of course, if they can even remove the screws that hold the cover.) The blade of the screwdriver becomes uncontrollable in my hands, and frequently it trips breakers, sends an electrical arc between phases, burns a notch in the shaft of the screwdriver and grounds out circuits. Troubleshooting for electrical outages, my favorite part of the work, is virtually impossible. Because of my tremors, I can no longer work at my trade.

Even without tremors, it was time for me to put my pliers away and quit twisting wires. It is unsafe for an octogenarian to climb ladders, stumble about construction sites and ply the electrical trade. I eased away from electrical work and took up the hobby of bird watching and bird photography. Even here my trembling interferes. I cannot hold binoculars still to see a clear image of a bird at a distance. The remarkable photographs that I once captured are a memory: My photos of birds in flight are blurry and obscure.

Of all the aggravations tremors have caused me, those that limit my birding are the ones I find most repugnant.

WORK-AROUNDS

Tremors are not painful. Compared to other maladies I have had in my long life (meningitis, kidney stones, diverticulitis and broken bones) they are more inconvenience than disability. I have been able to mitigate problems by using a few common sense techniques.

For now, my left arm, wrist and fingers do not tremor as badly as my right. So, I use the left more, or I use it to steady my dominant right hand.

Heavier or larger forks and spoons simplify eating. Sales clerks are gracious to fill out checks for me. Releasing any fish I catch is more pleasant and environmentally friendly than cleaning them, though not as tasty. I wrap tape around the shaft of a screwdriver to insulate it, if I must work in an energized electrical box. By bracing binoculars on a tree or post, or using a tripod or anti-vibration-assisted camera I can occasionally document a good bird sighting.

And I crack self-deprecating jokes in situations where my tremors might make others feel awkward.

MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS

Twenty-five years ago, when my tremors were just a twitch, I consulted a neurologist. The good news, he said, was that I did not have Parkinson's disease; the bad news was I had "familial" tremors. Both conditions are disorders of the central nervous system, and both share the symptom of tremoring. Parkinson's is the more severe malady. Familial tremors, as the name implies, typically runs in families.

The primary symptom of familial tremors is treatable, the neurologist told me, but its causes are not well understood and there is no cure. He said, "Prescription medications usually help."

For the next two decades I took medicine; first one type, then another, then another — all with only moderate relief. The side effects were unpleasant. The drugs made me groggy or queasy or both. The tremoring increased. It seemed to make little difference whether I took medications or not. I finally quit them altogether and felt better.

LEARNING ON MY OWN

Even before the diagnosis, I had noticed that men on the maternal side of my family began shaking as they grew older. Women sometimes seemed afflicted too, but their symptoms were quivering voices and shaking heads (a la Katharine Hepburn) rather than trembling hands.

Researching, I learned that what my neurologist had called "familial tremors" is more commonly called "intentional" or "essential tremor."

The most helpful book I read was "The Facts of Essential Tremor: Expert Advice for Patients, Carers and Professionals" by two British scientists, Mark Plumb, a geneticist (who has the malady) and Peter Bain, a clinical neurologist. The book synthesizes a vast amount of scientific data in layman's terms.

The book's foreword says, "Essential tremor is one of the most common afflictions of humans, affecting about 1 out of every 100 persons. Yet it is not recognized, often misdiagnosed, not well treated, and not fully understood."

Plumb and Bain list treatment protocols that have been investigated. I tried many of those protocols without success, including: 1) avoiding caffeine, 2) smoking cannabis, 3) drinking booze, 4) taking three kinds of prescription medications.

I did not try Botox therapy because it was expensive, not covered by my insurance and promised only temporary relief. I did not try sound wave therapy, which destroys some brain cells, because it could only be done for one side of my brain and was irreversible.

I was skeptical of deep brain stimulation (DBS), an invasive medical procedure. Plumb and Bain say that the surgery "is reserved for those patients who have particularly severe/disabling tremor which does not respond to medication."

The therapy involves two surgeries:

◼️ One to drill a dime-size hole in the skull — while the patient is wide awake — inserting probes into the thalamus, tunneling under the scalp to connect a set of wires to a signaling device and introducing a continuous electrical stimulation into the brain via probes.

◼️ A second surgery to implant a power source just beneath the skin between the breast and neck.

Choosing this treatment never entered my mind. It seemed too much. Too radical. Like swatting a mosquito with a sledgehammer. I put the idea out of my brain.

OUT OF THE MOUTHS OF BABES

Lauren Kinsey Vineyard is my niece. When she was 3 years old, I taught her to call me "my sweet Uncle Jerry." I never imagined then the powers of suggestion over me I was granting the child I called "my sweet Lauren."

When she became an adult and a surgical nurse at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Medical Center, she witnessed a transformational procedure. A person with profound tremors would come into the surgical theater and with only local anesthesia would have their brain operated upon. Within minutes, it seemed, the patient would be able to perform tasks like writing their name.

"Sweet Uncle Jerry, you ought to talk to this lady surgeon about having that procedure," Lauren said. "It's remarkable. It might help you."

Eight years after she first told me that, my tremors had increased another 25% and I found the resolve to take my sweet Lauren's advice.

Deep brain stimulation can be performed on a patient at UAMS only after a significant number of preliminary psychological, neurological, physiological and metabolic tests to verify the surgery is appropriate. The neurologic team is clear about the risks involved and possible adverse outcomes. The covid-19 pandemic burgeoned when I was scheduled to receive these preliminary tests, and so it took an inordinate amount of time for me to complete these pre-op protocols.

The delay worked in my favor, because it allowed me to talk with other people who had already completed the process.

I talked to four people who had undergone deep brain stimulation. Two of them had Parkinson's disease; one I understood had epilepsy; and the other had familial tremors. All of them used to tremble worse than I did. They all had used the same team of physicians I was planning to use. I was particularly interested to hear one of them, an avid bird watcher, could now hold his binoculars steady. They all reported good results.

WITH EYES WIDE OPEN

On the day a patient undergoes deep brain stimulation they are fitted with a contraption that looks like a medieval knight's helmet. The medical euphemism for this contraption is a "halo." To my mind, the halo seems more akin to the instrument of torture in Alexandre Dumas' book "Man in the Iron Mask." I understand such euphemisms are used to quell patient anxiety, but I found the deceptive use of language patronizing.

The "halo" is fastened to the skull with pins and screws as a necessary preliminary step to assist the surgeon's precision as she places electrodes within the thalamus with 1-mm accuracy. The injection of the local anesthesia while fitting the halo is the most painful part of the five-hour deep brain stimulation procedure.

Then I was rolled into surgery on a gurney. The sedative they gave me eased my anxiety; but I was wide awake throughout the procedure.

It was not like a dream, it was not like an ordeal, it was more like a hopeful adventure.

Next: On Sept. 27 in Style, Jerry Butler describes what it was like to experience brain surgery with his eyes wide open.