They say you shouldn't meet your heroes. I agree.

You probably shouldn't have heroes. For sure, you shouldn't make a hero of someone you don't know.

But we all do things we shouldn't do. And I met Paul Newman once.

How could an American of my generation and background not feel a frisson of excitement upon meeting him? He seemed to have been the last of his kind, the last of the genuine movie stars from the time when movies mattered in a way they no longer can.

He was in the same league as Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne and Gregory Peck, as Ted Williams and Hank Aaron. He was the exemplification of a particular kind of masculinity, one of the private heroes against which a young man might measure himself. He was good at whatever he did, but he managed to be self-effacing. He was remarkably attractive, but a good husband.

Our meeting was a work thing, arranged by publicists for promotional purposes, but it felt like a real meeting, which is probably why Paul Newman was Paul Newman. I've met Tom Cruise and Bill Clinton too, and whatever you think of those guys, when you're in a room with them you understand exactly why they are who they are.

This is not the case with all famous or successful people. Most of them, after you get over the initial surprise of recognizing them, register as pretty ordinary. You grow up, you learn that there is not that much difference between you and those you admire or detest — the human spectrum is broad but limited. And it is possible to be noble one minute and craven the next.

Most famous people, you realize, are where they are because they are good at what they do and experience some luck, not because they are blessed/cursed by the gods. One of the reasons it's good for aspiring creators to be around successful creators is because they can see them up close and take their measure and realize that there's not much difference between them and regular mortals. Most famous people aren't all that intimidating.

But when I met Paul Newman my first thought was "his eyes really are that blue."

It was in a ballroom at the Ritz-Carlton in Chicago, 20 years ago, at a small news conference to promote his then current film, Sam Mendes' "Road to Perdition."

If you remember the film, you might think of it as Mendes' follow-up to "American Beauty," the 1999 black comedy that was his film directorial debut. It starred Kevin Spacey as an advertising executive who, in the midst of a midlife crisis, becomes infatuated with his teenage daughter's best friend, played by Mena Suvari.

While "American Beauty" has not aged particularly well, it won five Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Spacey), Best Original Screenplay and Best Cinematography. It also won six of the 14 British Academy Film Awards for which it was nominated: Best Film, Best Actor, Best Actress (Annette Bening), Best Cinematography, Best Film Music and Best Editing.

But even though "American Beauty" had won these accolades and received excellent reviews, there was, by 2002, a palpable backlash against the film. Mendes had something to prove — his second film needed to validate the first. He chose a much different story, a Depression-era gangster movie with Shakespearean overtones and minimal dialogue.

EMERGING FROM 'PERDITION'

"Road to Perdition" was a big deal, with a big cast that included Tom Hanks playing against type as a Depression-era hit man named Michael Sullivan working for Irish mob boss John Rooney (Newman) in Rock Island, Ill., and around the Midwest.

Rooney raised the orphaned Sullivan, and his affection for him outstrips that which he has for his biological son Connor (Daniel Craig), a feckless and craven killer. The story, adapted from a popular graphic novel, sets Rooney's actual son and his surrogate son against each other, with the conflicted old man in the middle.

One of the advantages of becoming an American movie icon is that people will ascribe some import to your every action or inaction. The fact that you are known and presumed to be well known by a great many people all over the world lends a certain gravity to your characterizations.

If you are cognizant of this thing deeper than celebrity, you can use it. You can even get to a place where you use your silences and pauses like the kickboxing stars use flying kicks and back flips. You can settle into an easy Zen-like state between acting and being, and let your co-conspiring audience fill in the details for themselves.

In "Road to Perdition," Newman uses this advantage; there are many years of goodwill ballasting his portrayal of John Rooney (who was based on real-life mob boss John Patrick Looney, who used his newspaper, the Rock Island Argus, as a weapon against his political enemies).

It's basically Lear with tommy guns; it holds up as a story about fathers and sons. It was a juicy part for Newman, and, as it turned out, his last live action movie role.

But the Newman I met in Chicago that day did not seem like a man near the end of his career. He was, as most movie actors are, smaller than expected, compact, with dimensions that fit well on the screen. He was mildly stooped and grinning, possibly a touch befuddled, an old Socratic figure. There was a playfulness to him — a measured, comic hesitancy meant to misdirect his audience from a keen predatory intelligence lurking just beneath the patina of Hollywood bonhomie.

You got the feeling that Paul Newman, even the grayed and wizened edition, took in and evaluated the entire room in seconds, that he knew exactly where the exits were and how many steps it would take to reach them. It was a little shocking to see him as an old man but the effect was not that different from seeing him in old-age makeup. That was still Paul Newman, that was still Hud, still Butch Cassidy, still Reggie Dunlop.

As a young actor Newman had a cockiness, an air of self-assurance that often as not manifested itself in a sort of insouciant brazenness. As a kid, he often played the charming insolent jerk barely capable of concealing his contempt for the straight world. He was easy to like, even when the characters he played — feckless Fast Eddie Felson in "The Hustler," bullheaded Luke Jackson in "Cool Hand Luke" — were petty and mean.

Newman was the rare method actor who didn't seem to take himself too seriously, who didn't so obviously and painfully draw from a well of real or imagined neuroses. Even when his characters were dysfunctional, they seemed capable of balancing their checkbooks, of negotiating an ordinary day without cutting themselves to shreds on reality's sharp edges. Newman was always the most unhurried — the most unfrenzied — of movie actors. And one of the most underrated.

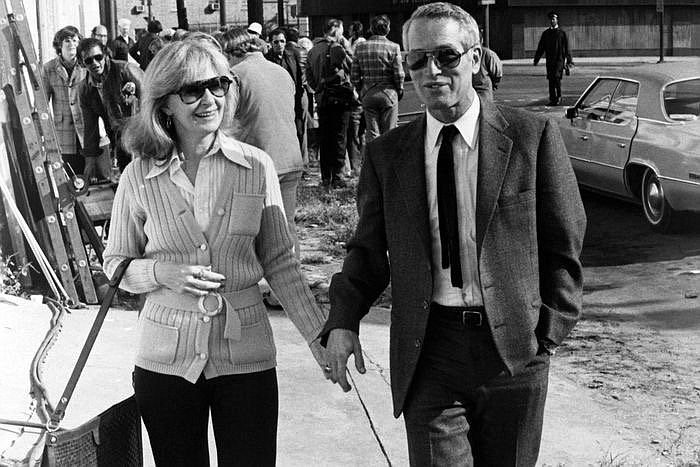

Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman are the subjects of the Ethan Hawke documentary “The Last Movie Stars.”

Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman are the subjects of the Ethan Hawke documentary “The Last Movie Stars.”

'THE LAST MOVIE STARS'

This isn't exactly the case Ethan Hawke and his confederates are making with "The Last Movie Stars," a six-part docuseries streaming on HBO Max that examines the lives and careers of Newman and his wife Joanne Woodward through the prism of their long and apparently genuinely happy marriage.

Hawke's working theory is one proposed by Gore Vidal: Newman and Woodward were the last people to be treated like genuine movie stars, to be both icon figures and relatively private. They were a kind of royalty, accorded a measure of dignity even though they were familiar to millions.

They were beloved, embraced by America in a way that isn't possible anymore.

Hawke wants to understand why, and having lucked into a mother lode of material, has launched an emotional investigation of their relationship to each other, which no one seems to have ever doubted was genuine and deeply romantic. (I remember reading an interview with a 60-year-old Woodward shortly after she appeared with her husband in 1990's "Mr. and Mrs. Bridge." She watched Newman's character die in that film, and, she said, the very thought of a world without Paul Newman brought tears to her eyes. Woodward, diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2007, is now in her 90s.)

In the early 1990s, Newman asked screenwriter Stewart Stern to interview him and his wife and dozens of their friends and colleagues for a vague memoir project. Newman eventually abandoned the idea and burned all the tapes, but Stern had them transcribed, and after he died a few years ago his children discovered them. They took them to Hawke in hopes that he might find a way to use them.

During the pandemic, Hawke managed to convince a number of his acting friends to read these transcripts. He got George Clooney to read Newman's words, Laura Linney to read Woodward's. Stage actor Brooks Ashmanskas plays their longtime friend Gore Vidal; Vincent D'Onofrio plays Karl Malden; Zoe Kazan plays Newman's first wife Jackie McDonald, nee Witte.

Other actors, including Hawke's daughter Maya and Sam Rockwell, also contribute their voices to the project, which otherwise consists largely of archival footage from Newman's and Woodward's films.

Near the beginning of "The Last Movie Stars," Hawke tells the story about how one Sunday his father took him to a matinee to see "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," and how, after that experience, the movies became his "church."

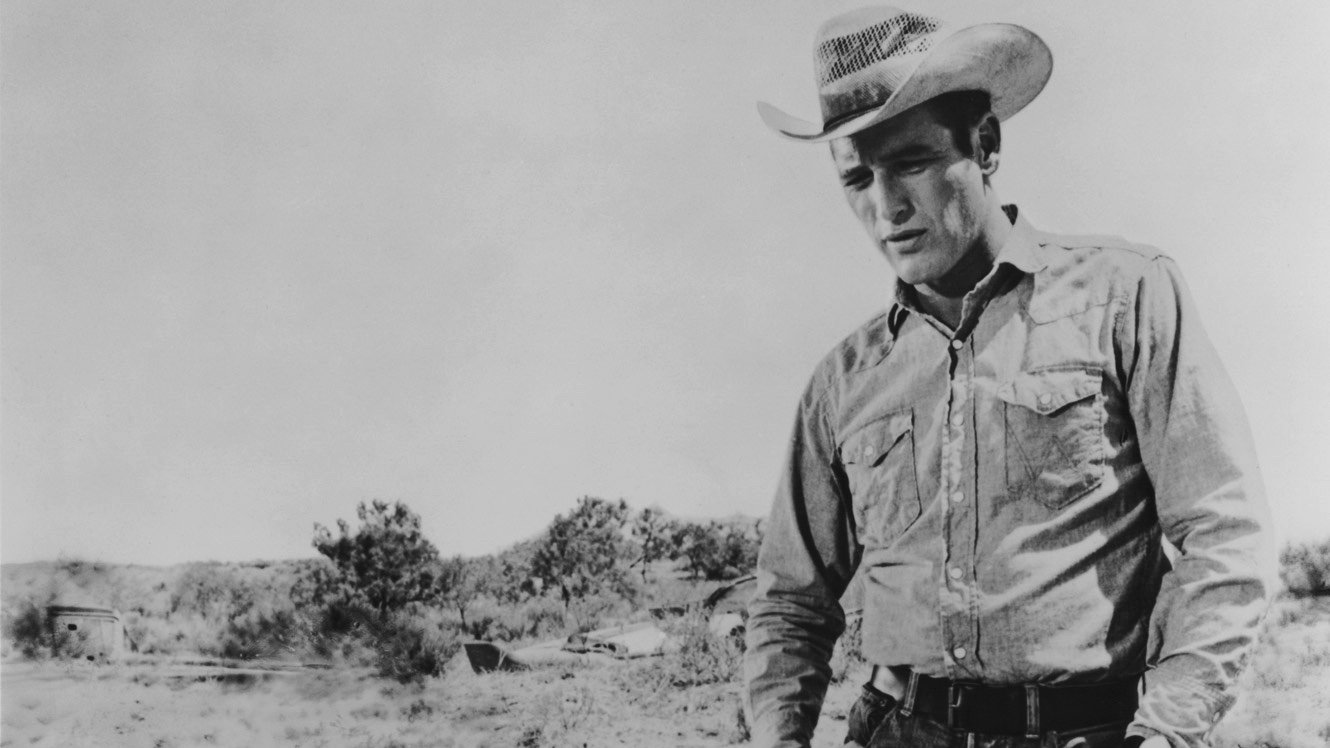

My experience is not much different; Newman might have been the most important American movie star of the early '60s — it's his performance in "Hud," not James Dean's in "Rebel Without a Cause" or Marlon Brandon's in "On the Waterfront" that revolutionized the way we receive flawed antiheroes as protagonists — but my personal Newman is from the late 1970s and early 1980s: specifically the Newman of the five years bookended by 1977's "Slap Shot" and 1982's "The Verdict."

We might think of this as Newman's period of transition from leading man to featured legend, but his work in these roles invariably elevated what could have been ordinary material to the level of genuine Hollywood art.

Newman was a great actor before that run — which also includes "Absence of Malice" and "Fort Apache the Bronx" — but this was when I began consuming Newman in real time. Like Hawke, I saw "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" when it came out, but for whatever reason Robert Redford made the bigger impression on me. And as far as I know, I was the only person who was left cold by "The Sting." (I have since revised my opinion; "The Sting" will never find its way onto my list of genuinely great movies, but now I get it.)

WHEN THE TWAIN MET

Woodward and Newman met in 1953, when both were cast in the premiere run of William Inge's summer romance "Picnic" at New York's Music Box Theatre. Woodward was an understudy, Newman was the nerdy rich boy foil to leading man Ralph Meeker's Hal, the kind of superficially carefree, self-destructive cad that Newman would become famous for playing. Newman was also married at the time to actress/model Jacqueline Witte.

While Newman and Woodward were attracted to each other from the beginning, she — according to The New York Times — "insisted that they spent the next several years running away from each other."

She became established in Hollywood before he did, a bonafide star before winning an Oscar for "The Three Faces Of Eve" in 1958. In the beginning, Newman worked in television, and his career was just beginning to take off when they were married.

That day in Chicago, Newman was more an impish avuncular comedian than I expected from his film work.

He was refreshingly honest; he told me he hadn't had a chance to see "Road to Perdition" yet, but that he didn't have to see the finished product to know how a movie of his had turned out. This one had turned out swell because there were good people working on it, it was a good script, and he had a good time making it.

He liked working with Tom Hanks, who has "the quality of not dodging things."

"There's no fancy footwork with him," Newman said, "no approaching things sideways." It was like Newman was talking about himself.

A Chicago-based reporter asked him how it felt to be back in the city and whether Newman — born and raised in Cleveland — has any particular affinity for the city.

"I love Chicago," he said, drifting into a reminiscence about his father's sporting goods store in Cleveland and how his family was able to survive the Depression through the forbearance of sporting goods manufacturers Spalding and Wilson, who at that time were based in Chicago. That made him feel good about the city, which was after all a cultural center, rife with creative energy and good restaurants.

Paul Newman stars as Hud Bannon in “Hud” (1963). (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

Paul Newman stars as Hud Bannon in “Hud” (1963). (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

THE MASCULINE LIBERAL

Then he quoted Al Capone. "All Chicago really needs is two good left-leaning newspapers."

This caused a ripple of nervous laughter.

Some asked Newman about his politics and his famous philanthropy.

"Aristotle said the greatest government is the government that has the least number of people at each end," he said, meaning the fewest rich and the fewest poor. "That makes sense. I don't think there's anything exceptional or noble about being philanthropic — what I don't understand, what I consider unnatural, is the opposite inclination."

"Pinko," no one called out.

Only 20 years ago you could be both a liberal and a paradigm of American masculine grace. Reading Newman's lines in "The Last Movie Stars," Clooney sounds an awful lot like him, especially when he's "doing" him. But Clooney is a villain to a lot of Americans these days in a way that Newman never was — Newman could pal around with former housemate Vidal (who once pretended to be engaged to Woodward as a beard for his homosexuality) and go to marches and make donations, and still command the respect and affection of people who voted for Richard Nixon.

That's not how we do things anymore. We don't go intertribal anymore. There can be no more Paul Newmans.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com