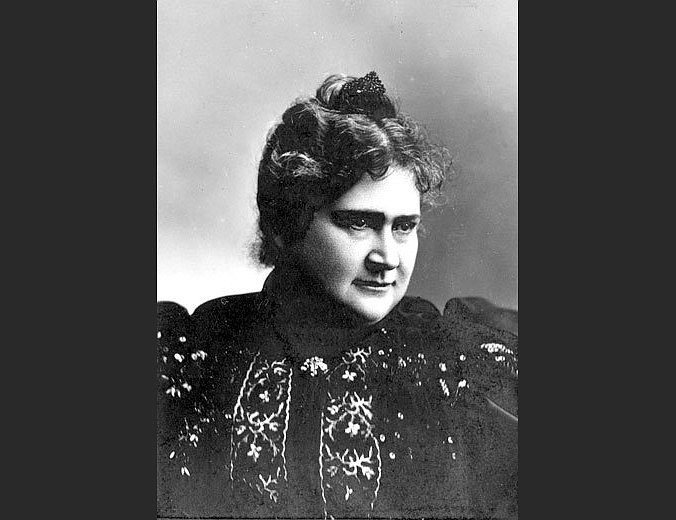

Alice French, under the pseudonym Octave Thanet, was a leading writer of local color stories and journalistic essays whose work was published in such national periodicals as the Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, Scribner's Magazine, and Century Magazine. Some of her best writing is based on the years she spent at her winter home in Clover Bend in the Black River swamp country of northeastern Arkansas.

Alice French was born on March 19, 1850, in Andover, Mass., to George Henry French and Frances Morton. The family later moved to Davenport, Iowa. After studying at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and Abbot Academy in Andover, she returned to Davenport. Her first published work was a sentimental story, "Hugo's Waiting," printed in the Davenport Gazette in 1871. However, the first work for which she was paid was "Communists and Capitalists, A Sketch from Life," published in October 1878 in Lippincott's Magazine. At that point, French took the pseudonym "Octave Thanet." She later claimed that she chose "Octave" because it was gender-neutral, and that she had seen the word "Thanet" written on a freight car in the Davenport yards.

Early in her career, French published stories with philosophical or political themes, as well as nonfiction stories such as "The English Workingman and the Commercial Crises," published in Lippincott's in 1880, and "A Neglected Career for Unmarried Women" (she herself was unmarried), published in Harper's Bazaar in 1882.

French launched her career by exploiting the new interest in local-color writing, with a particular interest in the laborers and capitalists in the growing towns and cities of the Midwest. In 1883, French and her widowed friend, Jane Allen Crawford, set up a permanent winter home at Clover Bend Plantation in Lawrence County. They lived there for several months each year until 1909.

"Thanford," as she and Crawford called their house, was also the setting for their literary and social activities, entertaining people with luxurious meals and fine wines in effective contrast with their wilderness surroundings.

The pieces French wrote as Octave Thanet are squarely set in the local-color tradition. The reading public wanted romance and moral uplift with realistic details of speech, setting and character types. French collected lists of curious dialect phrases and pronunciation, folklore and superstitions, and retold Lawrence County legends about conjurers, ghosts and family feuds. The planters she describes are intelligent, brave, shrewd and successful; in general, her lower-class farmers and laborers are shiftless, sickly and lacking foresight or ambition. She generally portrays Blacks as merely ridiculous. There are notable exceptions, like Dosier, the heroine of "Sist' Chaney's Black Silk," which depicts the generous and compassionate love of a Black bathhouse attendant in Hot Springs for her dying sister.

In her Arkansas stories, the narrator is the superior outsider, reporting the shocking, amusing or irritating ways of people who are clearly her — and her readers' — inferiors. However, her work exhibits narrative skill and a wry sense of humor. In 1891, the Atlantic Monthly published two of her nonfiction pieces, "Plantation Life in Arkansas" and "Town Life in Arkansas," in which she presented a generally positive picture of the state. In these pieces, she poses as a member of the group she describes: "We have the virtues of our vices in Arkansas." French defends those aspects of Southern life that make good stories and says that life in Arkansas is "more attractive than anyone who does not live in the state will believe."

In the 1890s, French published 10 books. Between 1896 and 1900, 50 of her stories were published, and four different publishers collected five volumes for reprinting.

In 1909, French and Crawford gave up their house at Clover Bend. French traveled widely in the United States, speaking for the conservative causes she embraced, adding to them her opposition to woman suffrage. She regularly attended the reunions of the Daughters of the American Revolution in Washington. Later in life she developed diabetes, and complications from the disease caused the loss of one leg and most of her eyesight. She died on Jan. 9, 1934, in Davenport and is buried in the Oakdale Memorial Park in that city.

A resurgent interest in American local color in the late 20th century revived Thanet's work. Some have read her stories as coded treatments of lesbian women. American feminist critics have found in some of her Arkansas stories a degree of sympathy for the conditions of poor Southern women, Black and white. The best of her Arkansas fiction demonstrates her skills: She could render the speech of common people; she had an eye for the colorful, arresting details of the southern landscape; and she presented a view of Arkansas that was popular with the American people. One of her reviewers wrote, "There is but one Arkansas, and Octave Thanet is its prophet."

— Ethel Simpson

This story is adapted by Guy Lancaster from the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas, a project of the Central Arkansas Library System. Visit the site at encyclopediaofarkansas.net.