This holiday season, when even occasional Christian worshippers are likely to head to church, is an apt time to remember the vital roles that Black congregations across Arkansas have played for their members — from slavery's antebellum era to today's tremulous race relations.

At least one venerable entity, Little Rock's First Missionary Baptist Church, traces its roots to before the Civil War. First Missionary Baptist, now at 701 Gaines St., is believed to be the state's oldest Black congregation. It was organized in 1845 when a slave named Wilson Brown was brave enough to ask his master to let him form a church.

The first service was held outdoors on May 2, 1847, at 10th and Spring streets. A few years later, the congregation moved into a building at today's Gaines Street location. It was replaced in 1882 by the present Gothic Revival edifice. In April 1963, exactly four months before his famous "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered the church's 118th-anniversary sermon.

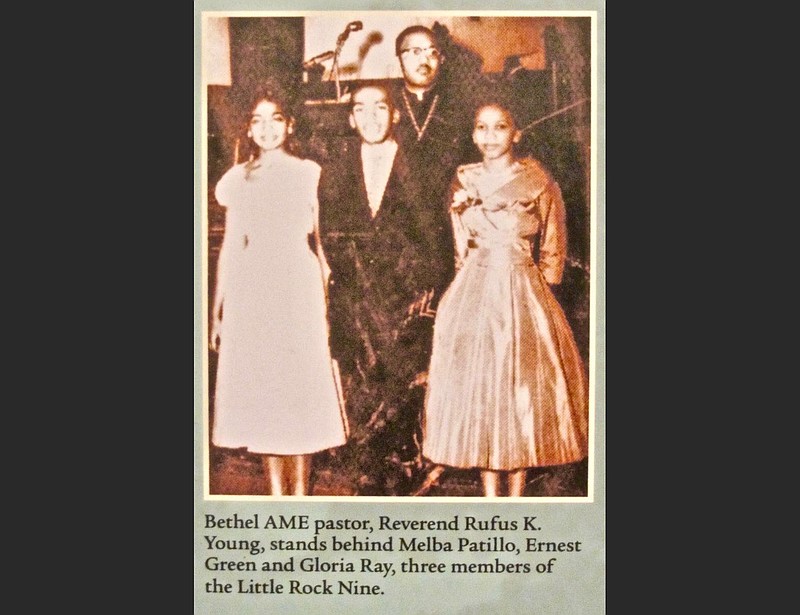

The history of Black worship in Arkansas is recounted with photographs and text at Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, 501 W. Ninth St. (mosaictemplarscenter.com). The largest artifact on display is an electric organ played by Little Rock native Art Porter Sr. The nationally celebrated musician performed as an organist at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church for 35 years until his death in 1993. That congregation, established in 1866 at 9th Street and Broadway, moved in 1970 to 815 W. 16th St.

"African-American churches served as the basis of social cohesion within Black communities," explains a posting at Mosaic Templars Cultural Center. "Prior to the Civil War, religion and the church allowed slaves to escape from the brutality of their daily lives.

"In most cases, slaves attended the same churches as their white masters. Some plantation owners allowed slaves to organize their own churches, but these early Black churches remained under the surveillance of white people who feared slave insurrections.

"In more recent times, Black churches hosted a variety of other activities, including civil rights events, youth organizations and education programs. Black churches emphasize education, morality and social cohesion. Thus these churches — both the buildings and the congregants — became important institutions in the Black community."

Smaller communities across the state have longstanding Black congregations. Bethel A.M.E. Church is the oldest religious building in Batesville. It was erected in 1880 from locally quarried ashlar sandstone to replace a wooden structure that had burned. Four of the Black quarry workers belonged to the congregation.

Arkansas' Black churches continue to serve their members, whatever adversities may arise. In 1963, St. John's A.M.E. Church in Pine Bluff was bombed during the period of civil-rights unrest across the South. An incendiary device shattered windows and set part of the building on fire. But quick discovery led to the blaze being extinguished before major damage. The perpetrators were never identified.

Less fortunate has been Helena-West Helena's Centennial Baptist Church, which was designed in 1905 by Henry James Price. He is believed to have been the only Black architect to design a building for a Black congregation. Increasingly decrepit over several decades, the structure was severely damaged in 2020 by a tornado. But a number of other Black churches in Helena-West Helena continue to welcome worshippers.