The tenants challenging Arkansas' criminal eviction statute, the only one of its kind in the nation, are now facing a separate civil eviction filing that could jeopardize their case against the state.

Cynthia and Terry Easley of Malvern filed a lawsuit in September in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, challenging the state's "failure to vacate" law, which charges tenants with a misdemeanor and fines up to $25 per day if they don't leave the property within 10 days of notice from the landlord.

Eviction for failure to pay rent is a civil matter in all other states, but in Arkansas, the law states that anyone behind on rent "shall at once forfeit all right to longer occupy" the rented space.

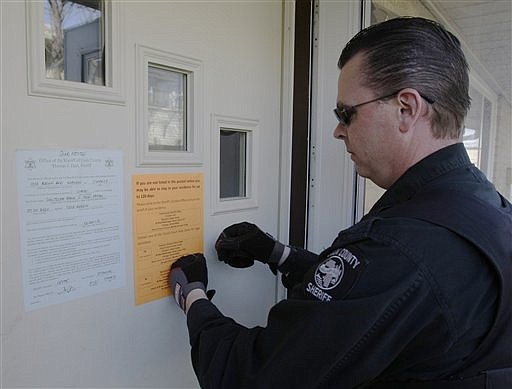

On Monday, the Easleys' landlord -- a new property owner as of November -- filed a complaint against them in Hot Spring County Circuit Court. It was not the first time the new landlord has served the Easleys with a notice to vacate, but it is the first legal step against them, said Natasha Baker, a staff attorney with the legal nonprofit Equal Justice Under Law, which is representing the Easleys.

The complaint falls under Hot Spring County's civil eviction process, which all 75 Arkansas counties and the 49 other states have.

Baker said this is "proof that landlords don't need the criminal eviction statute in order to address tenant-related issues."

If the Easleys are forced to move, the defendants in the Easleys' lawsuit could try to use the criminal eviction law to get the case dismissed, Baker said.

The defendants are Hot Spring County Prosecuting Attorney Teresa Howell and Sheriff Mike Cash. Under the statute of limitations within the criminal eviction law, Howell would have a full year to prosecute the Easleys after they vacate the residence. Their previous landlord ordered them in April to move out within 10 days.

The Easleys fell behind on rent in August 2020 after a broken water tank left them without running water, Baker said. The expenses accrued buying water and renting a portable toilet prevented them from paying rent, which was waived for a month. They still live in the same unit and still do not have running water, Baker said.

Since the threat of prosecution against the Easleys would remain for a year after moving, they would still have a case against the statute if the civil complaint against them is successful, Baker said.

Two previous challenges to the criminal eviction law were dismissed, in 2017 and 2020, because the plaintiffs eventually were no longer under threat of prosecution.

Also in 2017, the Arkansas Legislature amended the failure-to-vacate law to remove the threat of jail time.

Tenants do not face potential imprisonment in civil eviction cases. Additionally, the landlord is the plaintiff in a civil eviction proceeding and must pay court costs, while tenants must pay court fees if they challenge a criminal eviction.

A number of Arkansas district courts have found the criminal eviction law unconstitutional, including Pulaski County in 2015. Artoria Smith, a tenant in Little Rock, did not comply with a notice of eviction and was convicted of a misdemeanor in district.

She appealed the conviction to Pulaski County Circuit Court, where it was overturned on grounds the failure-to vacate statute violated a tenant's constitutional right to due process.

Baker said in September that the Easleys' lawyers were looking for more plaintiffs to form a class-action suit to keep the case alive long enough to reach a ruling instead of meeting the same fate as the previous two challenges.

Anyone who has been affected by the failure-to-vacate law anywhere in the state since Sept. 2, the day the suit was filed, is eligible to join the plaintiffs, Baker said.

There are no other plaintiffs as of this week, she said.

"If the law changed as a result of our case, that would affect everyone in the same position as the Easleys, regardless of whether they were named in the lawsuit or in personal contact with us," Baker said.

The Bowen Legal Clinic at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock is also representing the Easleys. Amy Pritchard, a UALR law professor at the Bowen Legal Clinic, could not be reached for comment.

Howell and Cash both sought in November to have the case dismissed, and in January, they reiterated their requests in a joint motion to stop the proceedings.

U.S. District Judge Susan O. Hickey denied the motion Jan. 21 but has not yet ruled on the requests to dismiss the suit.

In addition to Pulaski County, circuit courts in Craighead, Poinsett and Woodruff counties all have made similar rulings against the criminal eviction law since 2015.

From 2011 to September 2021, 324 tenants were arrested under the failure-to-vacate statute, according to the Arkansas Crime Information Center. The number of failure-to-vacate arrests per year did not exceed 30 after 2014, when it peaked at 70, according to the data.

The Easleys' predicament could have been avoided if Arkansas had a way to enforce a mandatory minimum standard for living conditions, said Lynn Foster, president of Arkansans for Stronger Communities and a former UALR law professor.

A 2021 state law created the state's first "warranty of habitability" standards, including hot and cold running water. However, the law "has no teeth" because it does not include consequences for landlords if they do not meet the standard conditions, Foster said.

Baker agreed, noting that the Easleys' current and former landlords did not restore running water to their apartment.

"The only remedy for the tenant is if they leave, so it's really not an implied warranty of habitability," Foster said.