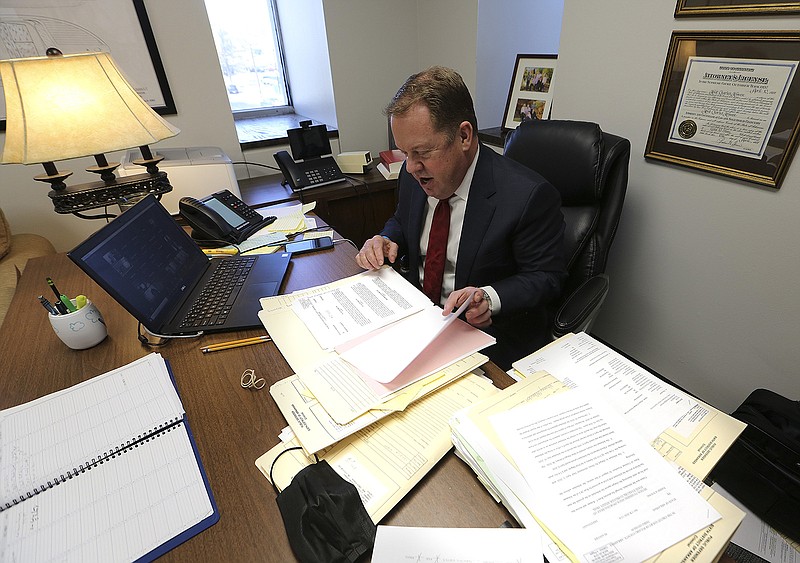

Pulaski County public defender Lou Marczuk had everything he needed for his next hearing -- except his client.

Tied to his desk while attending court by videoconference Monday, Marczuk could only call the defendant and hope she answered.

Keeping an eye on his computer, he placed his phone on top of a spread of case files and dialed.

During the next 8 minutes, Marczuk succeeded not only in reaching his client but in dealing with three other hearings.

Throughout the day, he worked with the same efficiency, toggling between the courtroom call, his phone and his case files.

"What the killer is, is you just keep getting more and more and more cases," he said during a break in the hearings.

Over the past two years, dockets across Arkansas have swelled as courts attempted to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

Backlogs have strained the entire criminal justice system, but public defenders, who were already facing rising caseloads and staffing shortages, said the added work has pushed them to the brink of an ethical crisis.

While court officials are working toward a solution, public defenders in Pulaski and Perry counties have announced plans to stop accepting cases if workloads aren't reduced to manageable levels by the end of the month.

At stake is more than just the constitutional right to adequate counsel for thousands of Arkansas defendants. Were court-appointed attorneys to refuse new cases, officials said the criminal justice system could enter unprecedented territory.

"If our public defenders stop accepting cases on March the first, we're going to be in a kind of trouble that I don't know how we're going to get out of, and I don't know how long it'll take to get out of," said Pulaski County Circuit Judge Cathi Compton.

In Compton's 3rd Division Circuit Court, attorneys dispensed with hearings at a dizzying pace Monday. A procession of defendants, appearing remotely, filed across courtroom monitors, each lingering only a few minutes as they heard updates on charges ranging from drug possession to murder.

That day, the court was set to blaze through 169 hearings -- roughly three times more than it processed on any given day a couple of years ago. Roughly two-thirds of the cases were assigned to a handful of public defenders.

Before the pandemic, Pulaski County public defenders kept their heads above water while handling about twice the maximum number of cases recommended by the American Bar Association, according to Kent Krause, chief deputy public defender.

But given current docket sizes and the challenges of negotiating cases remotely, it has become difficult for attorneys to reach resolutions.

"It's kind of a charade that is going on here," said Krause. "The bottom line is little to nothing is going to trial."

It isn't only happening in Little Rock, and public defenders aren't the only ones affected.

Managing case backlogs and virtual court has also strained prosecuting attorneys. Since the start of the pandemic, caseloads have tripled for prosecutors in Pulaski County, according to John Johnson, chief deputy prosecutor.

Swelling dockets have left at least one prosecutor carrying upward of 800 open cases.

The toll of the workload is evident in the number of attorneys leaving the office. Since September of 2020, Pulaski County prosecutors have seen an attrition rate of 50%, Johnson said.

Unlike public defenders, prosecuting attorneys carry the full weight of a court docket because each criminal case requires a prosecutor. Johnson noted, however, that caseload comparisons between the two offices are complicated considering that his counterparts have fewer attorneys.

Despite the strain and turnover, Johnson said his office continued to rise to the demands of the court.

"I don't want to come across as saying we are unable to do our job, because we are," he said. "But it comes at a toll."

As an indicator of the inefficiencies of virtual court, Johnson pointed to the number of cases his office resolved before and after the pandemic. In the year preceding March 2020, prosecutors closed 7,421 cases. The following year, the office resolved only 3,106 cases.

"Bear in mind that we're doing full-time Zoom court," said Johnson. "That's not the result of just sitting and doing nothing."

The state Supreme Court suspended jury trials and other in-person proceedings in all courts in March of 2020. After justices lifted the order in May, discretion returned to presiding judges.

With covid-19 cases in Arkansas declining, some judges are planning to resume in-person hearings in hopes of dispensing with the backlogs. Starting Monday, Compton will open her courtroom for hearings, including bench trials. She plans to resume jury trials next month.

Still, Compton noted that managing her court still involves some challenging calculus.

"I have the due process rights of the defendants, I have victims' rights, victims' family rights, I have the safety of my own staff and the safety of everybody who comes into the courtroom -- the public's safety," she said. "It's a pretty delicate dance, and I don't know if I'm dancing very well, although I'm trying very hard."

When cases do receive a trial date, it is often months away. While attorneys need enough time to prepare for trials, waiting too long can complicate the pursuit of justice.

"Victims disappear, cops quit ... evidence gets lost, memories get worse," said Marczuk.

With so many cases competing for limited trial spots, attorneys are having to prepare arguments for an increasing number of cases on any given day. As Marczuk scribbled down tentative trial dates, he noted that before the pandemic he might have had to prepare for eight to 12 possible trials on a busy day. Now overloaded courts are tentatively scheduling up to 20 trials a day, he said.

Most public defenders, already laden with other duties, often don't have time to prepare for that many trials.

Staying in touch with clients, a long-standing challenge for public defenders, has become harder as the timeline for cases has lengthened. Many defendants move and change their phone numbers often.

Pulling up his contact list, Marczuk pointed out clients who had changed numbers at least three times since he began representing them.

Meeting with clients in jail, a duty public defenders handled with relative ease before the pandemic, has become increasingly complex.

While conferring with clients in the Poinsett County jail last month, Brian Miles, managing public defender based in Jonesboro, found every visiting room occupied by inmates in quarantine. Each time he met with a client in person, he said he risked catching the virus since the jail couldn't reveal inmates' medical information.

"We don't know if the person we're talking to has covid or is in quarantine because the jail can't tell us," he said. "It's more stressful right now."

For public defenders meeting with clients in larger jails, scheduling visits using virtual portals has proven challenging. The Washington County jail, which held 467 pretrial inmates early last week, provides only 12 one-hour virtual meeting slots a day, according to public defender Blake Chancellor. Law enforcement, bail bond agents and other court officials are all competing with public defenders for those 12 slots.

While Chancellor said jails may be able to schedule multiple shorter meetings within one slot, the system doesn't come close to matching the demand.

"If the public defenders scheduled time solely, and nobody else took a spot for those 12-hour spots, I'd get to talk to my clients as close as face to face as I can nowadays for [on average] one hour every 39 days," he said.

To supplement the video sessions, the Washington County jail offers an email service for pretrial inmates. But with public defenders already facing an uphill battle building trust with their clients, Chancellor said communicating via email is a poor substitute for face-to-face meetings.

"Would you like to talk to your doctor about a cancer diagnosis just via email?" he said. "You want to hear a bad prognosis and never see the face of that doctor, never sit in front of them and be able to communicate with them about what effectively will be years of your life?"

With public defenders' offices lacking funds to hire support staffs, some attorneys are having to shoulder tasks normally assigned to secretaries or inspectors along with their legal duties.

Sandy Cordi, a Washington County public defender, manages a caseload that has topped 400 felonies. As one of two public defenders certified to handle death penalty cases in her district, Cordi often oversees the intricacies of what can be years-long legal battles.

"There've been people that have been put to death that were later exonerated," she said. "This is something that we take very seriously."

But throughout the day, Cordi also has to spend time entering data and scheduling appointments. Since her office is short on investigators, Cordi will occasionally visit crime scenes and conduct street investigations for trials.

"We need more support staff," she said. "Our secretaries, our legal specialists here are excellent, but there's only so much time they have in the day."

To ease the burden of mounting caseloads, court and state officials are mulling solutions. In Pulaski County, public defenders and prosecutors have proposed additional courts to siphon cases away from bloated dockets. Staffing these courts with judges, attorneys and court workers would require significant state funds.

On Thursday, Krause said ongoing talks with Gov. Asa Hutchinson's office were moving in the right direction.

Krause suspected that a study of caseloads across the state would indicate that many other public defender offices would benefit from a solution similar to one he and his counterparts in the prosecuting attorney's office had championed.

"It's a problem that just doesn't affect our clients," said Krause. "It affects everybody."