Tornadoes have long been a fact of life in Arkansas. In recent years many lives have been saved by radar and early warning systems that organizations like the National Weather Service operate. Modern communication like radio, TV and online devices alert people of a storm's potential arrival.

Looking back a century or so, tornadoes were all too common in an era before such modern warning systems existed.

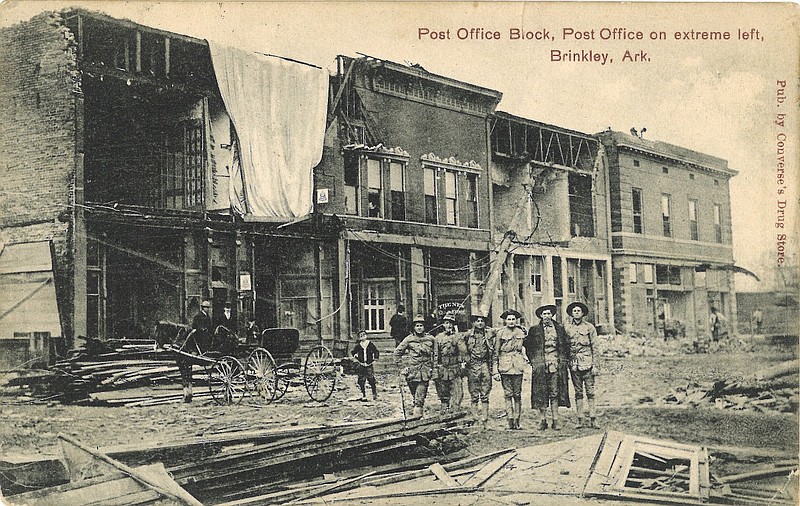

One of the most devastating tornadoes in state history struck Brinkley at dusk on March 8, 1909. At the time the storms were called cyclones, using the tropical storm terminology. Newspaper accounts and on-the-scene photographers left a remarkably detailed account of the impact of the tornado and driving rains that slammed into the town.

Reporting the day after the storm, the Arkansas Gazette said of Brinkley that it "was a well-appointed, prosperous, happy little city of 4,000." It began in 1872 as a railroad town, named for Memphis businessman Robert Brinkley, an early promoter of the railroad's path through Monroe County.

A business center for the thriving agricultural, timber and railroad industries, Brinkley was home to stores, hotels, churches and homes ranging from upscale to humble, especially in the Black section of the city. Everything would change in the minutes just before dark on March 8.

The tornado hit Brinkley at 7:07 p.m., documented by the Monroe County Bank clock's hands, which stopped when the bank was ripped apart. A vivid description from the Arkansas Gazette described "wind like an explosion of dynamite scrapped through the town and, as with a billion hands wrenched, tore and struck down with hideous wails and terrible crunches."

Newspaper accounts recorded a litany of miraculous escapes and heartbreaking losses of life and livelihoods in an era when almost nobody had tornado insurance.

The largest concentration of people in Brinkley when the storm struck was at the town's largest hotel, the Arlington. Some 75 guests were staying there, most apparently in the dining room when the storm blasted into it, taking away most of the top floor of the two-story lodging.

Sixty guests were rushed into a central hallway by hotel owner Gus Rusher, which likely saved their lives. Two guests upstairs in their rooms dived to the floor as the hotel began to come apart and were saved when their beds stopped the falling ceiling a couple feet over their heads, allowing them to crawl from the wreckage.

Nine kitchen employees, all Black men, were saved by a large iron stove behind which they took shelter and which blocked most of the falling wall and ceiling.

Rusher had poured all his savings into the business and watched it become an uninsured loss in a matter of seconds. He would later build a new hotel, the Rusher, near the depot, which still stands today, housing a regionally known bridal store but no rooms for rent. The city lost all three of its hotels that fateful evening: the Arlington, the Southern and the Brinkley Hotel.

John Starrett, state manager for the Nebraska Bridge, Supply and Lumber Company, was in his second-floor office on Cypress Street; he died in the building collapse.

Some victims were apparently never identified. Per a newspaper account, "A woman's shapely hand, white and bearing all the evidence of refinement and freedom from toil" was found near the railroad tracks. No woman's body was found missing a hand.

The difference between life and death seemingly was determined by inches of where people sat. A Mrs. Darden, along with her 10-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter, were in one room of their house when it was ripped apart by the tornado. Mrs. Darden was crushed to death by the falling ceiling, while the children were saved by the shelter of a sturdy table which shielded them from the falling ceiling.

Rescuers later reported that the son of Mrs. Darden crawled from the wreckage of his home, with tears streaming down his face, and helped rescue his trapped sister and recover the body of his mother.

Other miraculous saving of lives were attributed to iron furniture. Two-year-old Robert Lee McKnight was asleep in his bed when his house was torn apart. His frantic father found him, still asleep, the wreckage from the ceiling blocked by the sturdy head and footboard of his bed just inches above his small body.

The miracles of lives saved continued with reports of the fate of the three children of J.C. Moshier. Daughter Hattie, age 12, was sick in bed with pneumonia when the storm struck. The winds that wrecked the house tossed a chair across her face without making contact; that chair protected her from the falling ceiling and walls.

Moshier's 12-year-old son and 16-year-old daughter were caught in the narrow space beneath the keyboard of a heavy upright piano after the storm tossed the piano over. The two children were thus protected from flying debris and falling timbers of the house.

Other miraculous stories almost defied belief. Two-month-old Louise Stovall was asleep in her cradle beside the family's fireplace as the brick chimney was torn apart into a shower of projectiles, filling the child's cradle with bricks. The little girl's brother rushed into the ruins of the house immediately after the winds abated, fully expecting to find his sister crushed. News reports were that, though surrounded by bricks, there was not a mark on the baby.

When the storm struck, Ed Livingstone was home with his wife and baby in one room at their New Orleans Avenue house. The tornado lifted the structure from around them and ripped it to pieces that were reportedly scattered for half a mile. The floor where the family stood was left attached to the foundation, with all the other floors in the home swept away. The only reported injury was a minor bruise to Mrs. Livingstone; otherwise the family was unharmed.

Another newspaper account offered the story of an unidentified Black man who was near the Rock Island Railroad tracks by the depot. "A negro was blown from the Rock Island tracks over 150 yards into the door of Douglas's drug store where he dropped on to his feet unharmed according to a story relayed by Dr. O.B. Irvan, an eyewitness. 'I was standing inside the door of the drug store a few seconds after the storm broke,' said the doctor. 'The cars on the Rock Island began rolling like they were pasteboard. The air became full of flying boards and the like. There was incessant lightning. The Arlington Hotel crumbled and I saw a big object come sailing through the air from the tracks toward the door. I thought it was a log, and dodged back in a second it hit--a negro, hat in hand ... He came sailing in like a bird or rather a ghost, for he looked like one, and landed on his feet ... he dashed out the door and was gone.' "

Bart Boyer was a barber with a shop at the corner of New Orleans and Cypress streets who relayed a dramatic account of his survival. "I was standing in the front of the shop when I was suddenly shot through the windows and carried through the air toward the Rock Island tracks," said Boyer. "All at once I was dropped and caught hold of a little tree ... and hung on. My clothes were torn to shreds and my body covered with bruises by the awful ride. As I lay there I looked up and saw the city hall collapse. It did not make a great noise--just sort of groaned and melted away."

Another prominent politician made his way to Brinkley the night of the storm. About 10 p.m, a shout of "halt!" rang out from a young guardsman who thought he had spotted a curfew violator. The guardsman soon found out he had detained U.S. Rep. Joe T. Robinson, who had come over from his home in Lonoke to offer his assistance.

It took the arrival on the scene of Monroe County Sheriff Milwee to keep the young man with rifle and bayonet from marching the congressman off to jail. The next day Rep. Robinson would step up to chair the finance committee of the newly formed relief committee.

As more reporters arrived on the scene the day after the storm, more collected tales of the fickle nature of the tornado began to appear in print. A heavy iron cookstove with the pipe still attached was reported to have been deposited in the backyard of Rev. T.H. Howard, who had been in town so long he was credited with preaching the first sermon ever given in the city.

A horse and buggy belonging to a Dr. McKnight were carried a half-block through the air and dropped into some telephone wires that broke the buggy's fall. The buggy was said to be "damaged" and the horse received "sustained strains which rendered him useless except as a plodder."

Over at the barn of J.R. Viney on West Cedar Street, a cow was carried through the air for a reported 60 feet, along with the barn. The cow was said to have been safely deposited with a broken tail to show for the aerial flight.

Brinkley Mayor Jackson discovered his favorite living room chair lodged upright and little scathed 20 feet up in a tree near his house, which was destroyed. At city hall, a child's book, "Ray's Primary Arithmetic," traveled three blocks through the air to lodge in the bell of the destroyed building.

The surgical precision of the storm was evident nowhere more than at the two-story building that housed Farrel Machinery. The wind lifted the roof and deftly removed the second story, then deposited the roof on the remaining ground floor, converting a two-story building to one with a single story.

The only store left intact in Brinkley was Brauda Dry Goods Company. The owner opened his store and gave mattresses and any other goods needed to those that had lost so much.

The work of recovery and caring for the homeless picked up pace in the days after the storm. A temporary lunch counter was set up in the center of the shattered town. It was stocked with donated supplies that soon came pouring off boxcars that reached the town from all points. Meals were served in the Southern Hotel in a partially sheltered room where the entire side wall had been torn away.

Sightseers began to come to Brinkley, some to help, but too many to gawk. Two days after the storm a headline read, "Sight-Seers Are Eating up Great Deal of Supplies Intended for Survivors." This problem was soon solved by the patrolling militiamen enforcing martial law as they began to put to work clearing debris any strollers who seemed to have no helpful mission.

To help accelerate the cleanup of massive piles of rubble, Governor George W. Donaghey sent two trainloads of convicts from the state penitentiary. The local citizens apparently appreciated the help of the striped uniformed convicts. On the first Sunday after the storm, local ministers held a special service in the school auditorium for the prisoners.

In a city that lost all but one of its churches, the faith community stepped up quickly to help. Dr. E.C. Morris, president of the Negro Baptist State Convention, issued a plea to "colored" churches to donate to the relief fund. "All colored churches in the state of Arkansas and elsewhere are hereby requested to take a collection on Sunday morning" (March 14).

Relief supplies picked up a rapid pace after the railroads offered free rail shipment. Soon carloads of supplies and building materials were donated by communities across the state. Money began to flow in as well to the relief fund: $900 from Stuttgart, $200 from Batesville, $350 from Newport, and $482 from Cotton Plant.

Even the state's theater community jumped in. The Elk's Minstrels gave a benefit performance to a packed house at the Capital Theater in Little Rock with proceeds of $143 going to the Brinkley relief fund. A benefit baseball game was organized between the Arkansas League Players and the St. Louis Cardinals.

On March 11, three days after the storm, the funerals began. Eleven victims were buried that day as a cold wind whipped through the local cemetery. Among those laid to rest was Nebraska Bridge Company's John Starrett. His young daughters stood crying by the grave in the rain and hail during the service.

The tally of loss took some time, but a week after the storm it was known some 35 had died, with an estimated 250 injured. The uninsured property losses were estimated to exceed $2 million.

Not only were homes, stores and churches lost, but the places people had earned their living. Brinkley Car Works and Lumber Company had employed 150 men before the storm, but with the factory in ruins, those men were out of a job. Both train depots, the Iron Mountain and Rock Island, were gone, along with the post office and the light and water plant.

Brinkley would rise again from the rubble because of a hard-working spirit and the help of so many from around the state. Today, more than a century after the "cyclone," the town counts some 4,000 people.

An earlier version of this column appeared in the summer 1995 issue of the Arkansas Historical Quarterly.