Sidney Poitier wasn't exactly an actor of my time. He was my parents' idol, someone from some bygone Black Hollywood era, usually filmed in a drab, colorless setting that bored a young kid.

Watching "A Raisin in the Sun" in a mostly white classroom, I itched in my seat. As Walter, Poitier expressed embattled notions of pride and put-upon inferiority, dignity and the feeling of oppressive futility that comes with swimming against the country's strongest, darkest currents. "I say 'I gotta change my life' and all you can say is 'eat your eggs,'" he bellowed at Ruby Dee, who played his wife, Ruth.

I felt deeply seen by this drama, about the struggles of a Black family on the familiar far margins of the American Dream. But my classmates were wholly unfamiliar with those struggles: racism, poverty, multigenerational living, the desperation of wanting to feel the cold curve of the brass ring of success. These were the types of conversations we had at home, in private, away from the vulnerability and the potential for ridicule that came with talking about "family business."

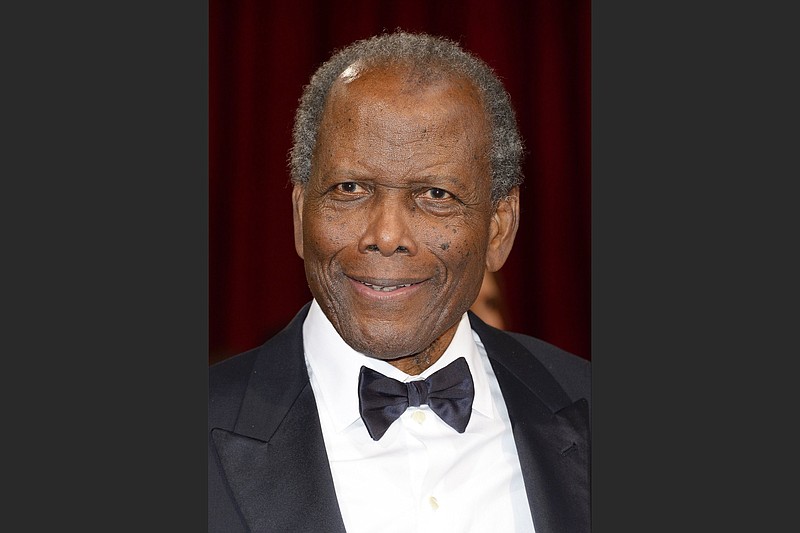

When Poitier died Jan. 6, at age 94, I thought back to how he conveyed worth and Blackness — sometimes together and sometimes separately — throughout his movies. His flight into our iconography came with highs in film — "Paris Blues," "In the Heat of the Night" — and Broadway misfires such as "Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights." But they all carried a through line of imprinting the value of Black stories into America's lobes.

Some of Poitier's most compelling performances could be linked to his personal history. Undereducated, semiliterate and Black, he was routinely and easily dismissed in his youth. At Poitier's first-ever audition, the casting manager told him to go back to being a dishwasher — not realizing that Poitier did, in fact, work as a dishwasher at the time. "I was, at that point, content to be a dishwasher," he said in a 2009 interview. But the comments offended him so much that he resolved to become an actor. He told himself, "I have to rectify that. I have to show him that he was wrong about me."

POWER THROUGH LANGUAGE

One of the most mesmerizing aspects of Poitier's acting was the power he packed into language. Early on, in 1967's "In the Heat of the Night," Poitier's character, Virgil Tibbs, has a tense nighttime exchange with the local chief of police. Tibbs' use of "whom" baffles and enrages the chief. The diction that the chief finds "uppity" is, in fact, an expression of Black audacity — daring to move in spaces where you're unwanted, to live.

Then there's "Lilies of the Field," from 1963. Gathered around the table with East German nuns, Poitier's character coaxes the sisters into saying "Amen" with the tinge of Black enunciation. There's a certain mirth in how Poitier plays Homer Smith, a roving Black journeyman who feels unmoored in an America experiencing a new immigration surge that left Black people swimming in the same soup as others. It's not lost on you that Smith, this Black man who is grudgingly thanked and constantly has his worth challenged, is also the man who teaches the nuns to how to speak American, with his unmistakably confident Black voice. "Well, it's English lesson time," he says, before leading them in a different sort of baptism.

This translator role often seemed to be Poitier's calling card. His career was studded with impressive moments of cinematic "zone-outs," when his ability to tap into some greater Black context seeped into scenes with a movingness that made the actor a living master class. Muddied and linked to Tony Curtis in "The Defiant Ones," about two escaped prisoners, Poitier's Noah Cullen bitterly opens up about the life he lost. He and his wife, he says, "worked 36 acres" on their land — four short of the 40 acres promised to formerly enslaved people. Packed inside that is the indictment of an America that consistently and consciously falls short of its promise. Scenes like that have their legacy in similarly haunting monologues, including Taraji P. Henson's dressing down of the engineer-room occupants in "Hidden Figures," and Chadwick Boseman sharing a formative childhood tragedy in "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom." (Boseman, in particular, seemed to channel Poitier's gift for tapping into a particular mixture of Black male pride, shame and tucked-away fury.)

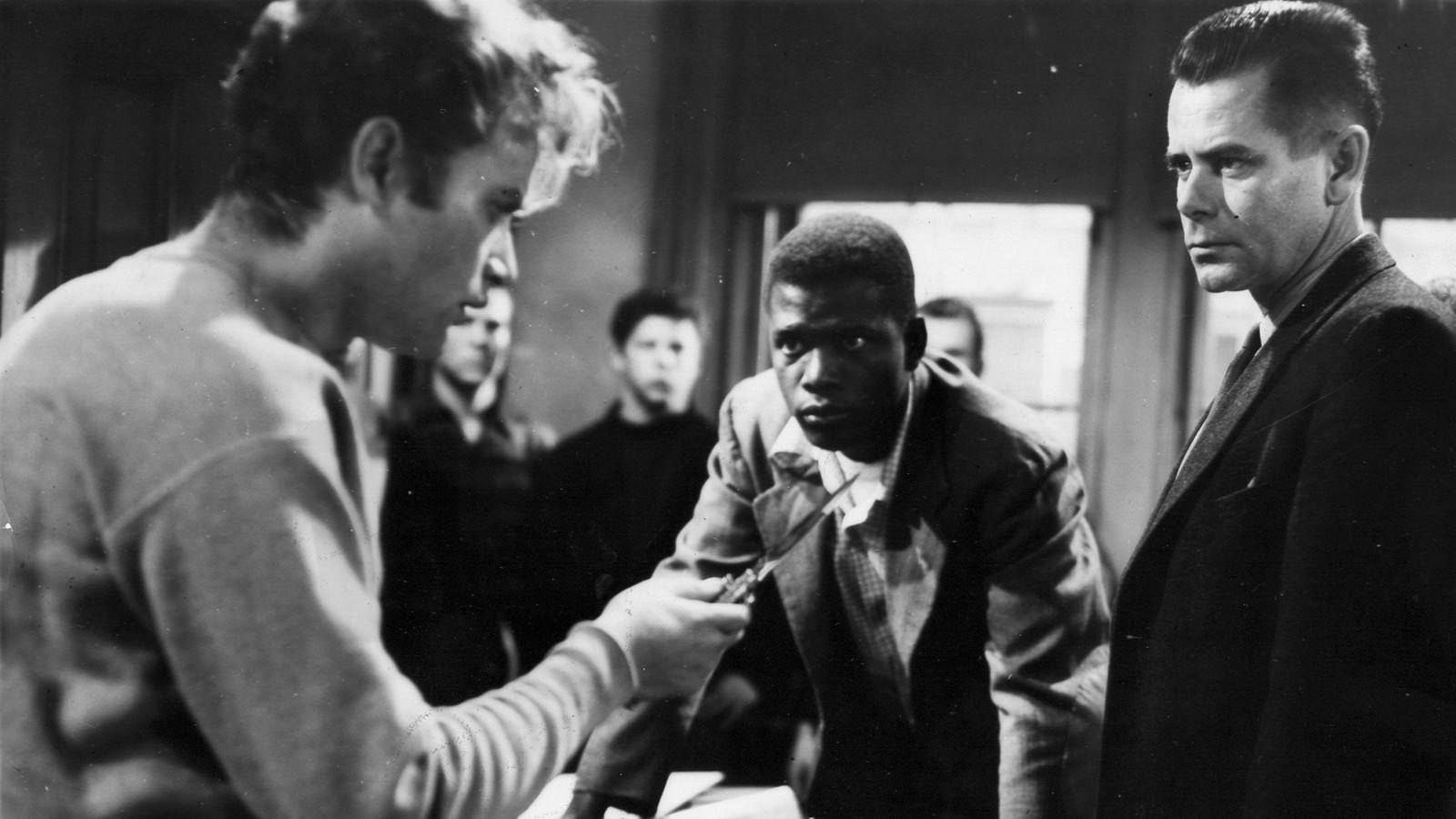

Sidney Poitier (center), stars with Vic Morrow and Glenn Ford in a scene from “Blackboard Jungle.”

Sidney Poitier (center), stars with Vic Morrow and Glenn Ford in a scene from “Blackboard Jungle.”

ART REFLECTING LIFE?

Poitier's career unfolded alongside the civil rights movement, and his films are rich with tension. "The Defiant Ones" followed a few short years after the Montgomery boycott. "Lilies of the Field" was released the year of the Birmingham church bombing, in 1963. "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" found itself situated between the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Reception of his movies is often divided between those who praise him as a bridge to white audiences — Poitier's characters often found themselves literally or figuratively linked to white characters — and those who criticize him for that. People debate whether his work was in tune with, or tone-deaf to, the racial arguments of his time. That conflict may be the inevitable consequence of a Black artist wading into mainstream racial narratives. It's part of, but shouldn't wholly define, his legacy.

What I loved about watching Poitier was the righteous rage that sat right beneath his skin; that implicit reproach of a broken American path that Black people held while trying to walk straight on it. I watched him like I watched my Pop-Pop when I was growing up: I recognized the careful, poised concentration it took to straddle pride and protection, not only of yourself but your loved ones. How heavy the tread was to constantly establish a truth about who you were, what you deserved and what you were worth. Poitier's roles were an exercise in control, dignity and comportment. That exercise is sometimes criticized as playing into respectability politics. But it was really about establishing the basic level of respect that comes with being taken seriously, and being seen as human.

With Poitier, it is hard, disingenuous even, to try separating the art from the artist: His life and career speak to the opportunity that lies in unifying them. In a joint interview with longtime friend and collaborator Harry Belafonte, Poitier talked about seeing himself, Black American stories and history on a specific cultural continuum. "We have a commitment to not only entertain people, but to say something during this time," he said in 1972 on the niche 1960s and '70s cable-access show "SOUL!," discussing his directorial debut, "Buck and the Preacher."

REPRESENTING REPRESENTATION

Poitier viewed the film, which charts the absence of Black struggles and contributions from histories of the New Frontier, as a project with an explicitly inspirational purpose: "We thought that Black people played an important part building the West. We wanted Black children to see that." Our current cultural conversations around representation, and the power of seeing yourself on the screen in depictions that are nuanced, emotive and whole, owe themselves to Poitier's steadfast commitment to drawing all of us into the Black mirror.

Growing up, I thought of Poitier as outdated, overly stately. It would be years before I understood that a long public life, lived in Black skin, will be up for scrutiny forever. It took time, too, to understand what I saw whenever he took the screen: a Black man, an artist, dedicated to creating the sort of tapestry that American cinema had rendered invisible for so long. An actor who made our Black American "family business" both timely and timeless.