Emily Kerns was less than a year out of nursing school when the covid-19 pandemic began two years ago.

Though hectic, a normal workday in the emergency room at Jefferson Regional Hospital in Pine Bluff had nothing on the "mass panic" covid-19 induced, she said.

"Everyone was coming to the hospital thinking they had covid because they were around someone who had covid, or they had a cough," said Kerns, who now works at her hometown DeWitt Hospital and Nursing Home.

The pandemic has wrought near-constant changes in the medical field, forcing health care professionals and educators to adapt quickly. Early-career nurses such as Kerns, as well as nursing students, have especially been thrown into the deep end.

They've had to learn remotely, care for gluts of patients, witness the varying effects of covid-19 on patients, and support their co-workers as well as patients and their families. All while remembering to take care of themselves in the process day in and day out.

The pandemic has highlighted the value of nurses, especially since the profession faces state and national shortages that existed even before the pandemic, said Melanie Mata, an assistant professor of nursing at Arkansas State University.

"They've been the ones that have really kept the pieces of the puzzle together," she said.

Early-career nurses started at time when experienced nursing were leaving the profession in droves, hospital administrators and researchers across the country have reported.

Throughout it all, young nurses have remained determined to stay in the nursing field despite the stress.

"You keep telling yourself that you're in the thick of it, and in a couple days or weeks or months, it won't feel like you're trying to pedal through mud, it'll feel like you're on a flat road instead of riding uphill all the time," said Emma Watkins, a student in Arkansas State's accelerated nursing degree program. "But right now, for nursing students, it does feel like we're riding uphill all the time."

'PATIENT ADVOCATES'

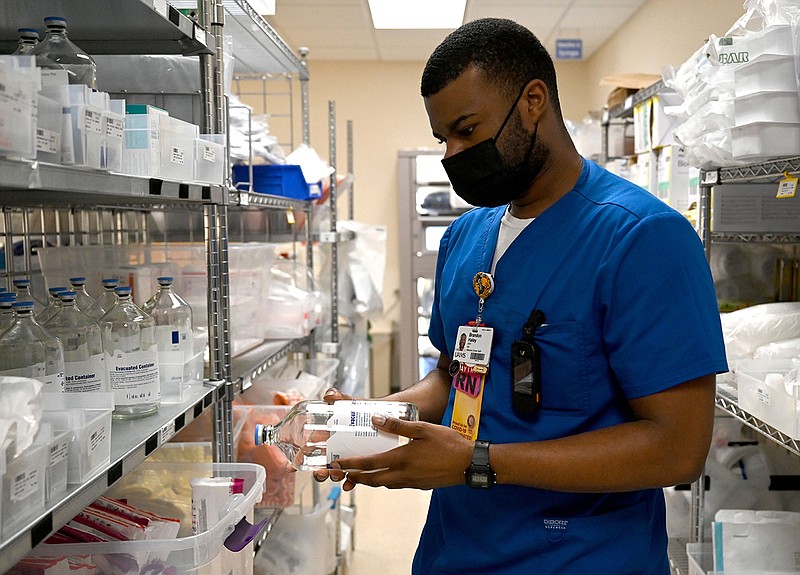

Brandon Haley completed the accelerated program at Arkansas State in August 2020 and started working full-time at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences later that year.

He was almost done with his degree when the pandemic began, and he quickly learned there are "added pieces to being a nurse in the pandemic." Learning on his feet was necessary, he said.

"In any profession where you're dedicated to helping people, you have to make sure that you're in a condition to pour into those patients and whatever health goals that they have," Haley said. "I think I had to get my mind right from the jump."

Students in Arkansas State's accelerated nursing program already have bachelor's degrees in other fields.

Watkins received a bachelor of fine arts in theatre from Arkansas State in 2018 and taught performing arts to elementary schoolers in Jonesboro for almost three years. She was already rethinking her career path before the pandemic forced schools to implement remote learning in the spring of 2020, she said.

"I realized that I absolutely loved kids and that I wanted to be able to offer a more intense degree of care that you can't always offer in the classroom," Watkins said.

She started nursing school in June and plans to graduate in August, hoping to work as a pediatric nurse.

Reasons for entering the nursing profession vary.

Some are inspired by family members, like Francesca Valdez, who was inspired by her father's work as a paramedic. She received her nursing degree from Crowder College in southeast Missouri in December 2020 and works at Mercy Hospital in Rogers.

Kamryn Alkire, who will finish his bachelor's degree in nursing at ASU in May, said he was "always interested in the medical field in some way or another," not only due to his father's work as a pharmacist.

"I grew up with an older family, so I unfortunately lost a lot of my family members and grandparents at a young age and spent a lot of time in the hospital with my relatives," Alkire said. "I saw firsthand how nurses can help families and patients in the darkest times of their lives, be that patient advocate for them and help relieve a lot of stress."

EDUCATIONAL ADJUSTMENTS

It became clear that the impending pandemic was serious when Arkansas Children's Hospital in Little Rock canceled clinical studies for Arkansas State's nursing students in March 2020, Mata, the ASU assistant professor, said. Other hospitals followed suit.

In a matter of days, faculty and administrators were able to create virtual simulations and assignments that helped students with critical thinking, which associate dean Dr. Sarah Davidson said is "the most essential skill in nursing."

Virtual learning lacked the hands-on experience of health care education and the level of engagement and support provided by in-person learning, Mata and Davidson said, so the ASU School of Nursing implemented a staggered in-person schedule. Students attended class on campus some days and via Zoom other days, with enough space between them in classrooms to adhere to federal covid-19 protection guidelines, Davidson said.

"At the time I was scared because I didn't know much about covid, but hindsight being 20/20, I'm grateful that the administration did what they did because had they not I do not feel that our retention rate for our students would have been as good," Mata said.

Arkansas State students officially enter the nursing school as sophomores. Alkire was in his second semester in the program when covid-19 forced the campus to close, and he said remote learning "made it more difficult to engage in all the aspects of nursing."

However, the ability to come back to campus in the fall and get clinical experience in hospitals meant Alkire missed little in the long run, he said.

He said he feels he has learned "everything I need to learn to be fully competent as a nurse," and he has accepted a post-graduation job at Conway Regional Medical Center.

Watkins said the pace of the accelerated program requires students to "live and breathe nursing," and the workload could be overwhelming. The current ebb in covid-19 hospitalizations has lightened some of the load.

"As of right now, there's room to get everything done, and we'll do everything we can to keep it that way," she said.

'HEARTBREAKING SOMETIMES'

Valdez started working at Mercy in January 2021 during a coronavirus surge. The work was "definitely a change of pace" from what she expected, she said, because a combination of factors created more work for nurses. The prevalence of the virus meant hospitals saw more patients, health care professionals who had covid-19 were unable to work on top of the shortage of nurses existing before the pandemic.

The team of nurses at Mercy "had to adapt and add more to our roles," Valdez said. Sometimes the respiratory department was overwhelmed, so nurses would help administer respiratory treatment. Other times, they would help with tech support in addition to responding to calls from patients, she said.

Nurses' roles of providing emotional support to patients and their families also had to adapt, since hospitals placed limits on visiting hours to mitigate the spread of covid-19.

"We've had to sadly keep [some visitors] away, not out of malice but out of protection, and sometimes that was a struggle, but they don't care, they just want to see their family member," Valdez said. "We're not just nurses for the patient, we're there for the family as well. I've had to pull them aside and say, 'It's OK to be upset, it's OK to cry, we're doing the best we can.'"

Watkins said her theatre background equipped her to face and handle "the full spectrum of emotions" that patients and their families feel when struggling with an illness or diagnosis.

"I love being a part of someone's best day, [when they are] giving birth to their children, and I respect the idea of being able to care for someone on the worst day of their life, such as being there for someone with a critical diagnosis or taking care of a family member who's just lost their loved one," Watkins said. "Despite me jumping into nursing school in the middle of a pandemic, being able to serve in that way is really what pushed me to go ahead and do it."

She called it "a privilege and devastating at the same time" to learn from other nurses at St. Bernards Medical Center, where she is working an externship, how to encourage sick patients' families without giving them false hopes.

Caring for covid-19 patients during the omicron surge in December and January was an eye-opening experience, Watkins said.

"[It's one thing to] think 'That's interesting' when you talk about 'covid brain' or a vocabulary deficit, but it's another thing to see a patient who's been having consistent seizures, and it's another thing to sit next to a patient who was diagnosed with the omicron variant in December and then it's January and they're fully intubated and their chances of making a full recovery are very slim," Watkins said.

The delta surge last summer, when Kerns still worked at Jefferson Regional, shocked her because of how many young people with no preexisting health conditions got sick, she said.

"It was hard for them to believe how sick they were, because typically, young people don't get that sick," Kerns said. "So it was definitely a slap in the face for us as well, trying to figure out the right treatment for those types of people. We were used to seeing older [covid-19] patients, people with a long health history, like kidney failure, hypertension or diabetes."

Patients with the omicron variant had less severe symptoms and did not have to stay hospitalized as long as delta patients did, Kerns said. She had moved to DeWitt Hospital by the time of the omicron surge.

The biggest difference between the two hospitals was that DeWitt has much fewer beds and resources, she said, so providing the best possible care for covid-19 patients is sometimes "just a matter of doing what we need to do keep them on the ventilator until we could get them to another hospital."

Treating a virus that "attacks everything" in a person's body can be difficult, Valdez said.

"Sometimes you just have to do everything you can to make them as comfortable as possible because they're maxed out on oxygen, so you have to hold their hand and help them through it," she said. "It's definitely heartbreaking sometimes."

SUPPORT AND SELF-CARE

Mata said Arkansas State nursing faculty "learned to have grace" for students during the pandemic, knowing it was challenging to keep up with their studies while adjusting to changes in their academic, professional and personal lives.

"We've had students who are paying their own way through nursing school ... and this is where we've had to have grace," she said. "We've worked around test times, we've worked around different things for them to retain them, because they're good students. I don't want to lose them to some bureaucratic rule we have about when to take a test."

Support from their peers as well as their superiors has been essential to maintaining nurses' mental health during the pandemic, according to Haley, Valdez and Watkins. They also said it's important to have hobbies and take time to recharge outside of work.

Valdez said caring for herself as well as her patients "takes a village," and sometimes it's necessary to acknowledge an emotional response to a tough situation in the moment.

"I try to be transparent with my patient and hold their hand, then excuse myself to confide in a colleague, or pray for strength," she said.

One of the most important things she has learned about the constantly changing nursing field is "don't be afraid to ask questions, because there are no stupid questions," Valdez said.

Haley described his colleagues at UAMS as "a big machine" that he often leans on for advice, and their support is crucial to his ability to care for patients, he said.

"They deserve 110%, and they can't get that out of me or any other health care professional if we're not checking in with ourselves," he said.

The comfort and the needs of patients remain on Watkins' mind after she leaves her shifts at St. Bernards, she said, and she seeks a balance between caring for them and catching her breath while "just chanting the mantra of 'keep going.'"

"I don't regret putting myself through a really difficult program and putting a salary and career on hold in order to meet the demand of care that is out there right now," Watkins said. "I think any nursing student who is in it for the right reasons would say the exact same thing."