Little Rock leaders including the mayor and police chief spoke Thursday night with activists, reformed convicts and teenagers about how best to support and mentor the city's young adults during the fourth in a series of town-hall style meetings called Courageous Conversations.

Officially, the topic of the night's meeting at the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center was how police and young people interact, but the conversation quickly turned to conflict resolution, mental illness and how teens can find mentors to help them learn from mistakes instead of having their lives derailed by them.

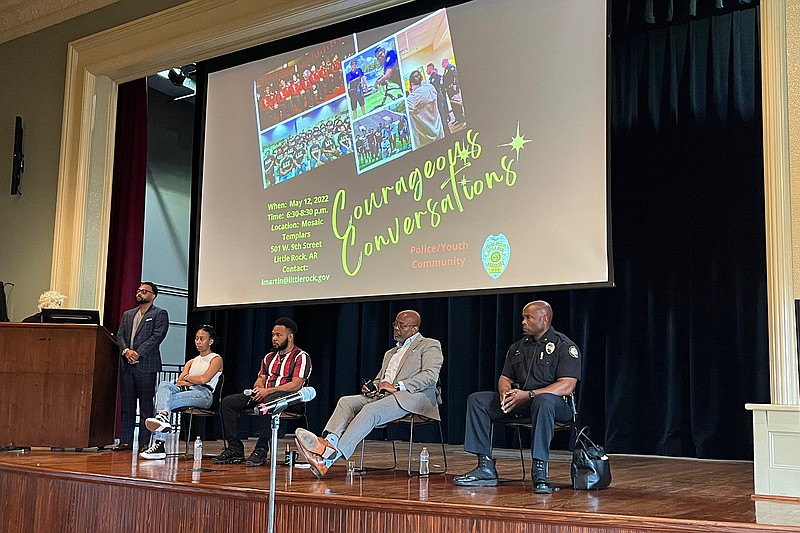

Myron Jackson, CEO of marketing agency The Design Group, moderated the panel, which consisted of Little Rock Police Chief Keith Humphrey, police Maj. Troy Ellison, activist Tim Campbell and Peyton White, a Little Rock Central graduate.

Ellison is over the department's Special Operations Division and oversees school resource officers in the city. Campbell is founder of The Movement and was recently named to the city's HOPE Advisory Council by Mayor Frank Scott Jr. White is a college student studying physics, and lent the panel additional perspective as a young adult from the city.

Compared with previous meetings in the Courageous Conversations series, the panelists on stage spoke far less than the audience members, resulting in a snappier and more organic back-and-forth between the participants.

A major topic of the night was anger, specifically when it came to young men feeling like their masculinity or status had been challenged.

A young man who didn't give his name told the panelists that the prevailing culture is that if one person in the family or friend group gets into a fight, everyone has to join in. He fought back tears, clearly bothered by the expectation of violence, saying that he didn't want to fight but didn't want to let his friends and family down.

Humphrey said he was concerned about the retaliatory violence in the city caused by deeply held grudges, especially by 18-to-24-year-olds.

"There's so much anger out here in these streets," Humphrey said.

That anger is often a result of fear, Campbell said, and can be a manifestation of the poor living conditions or unfair treatment that teens see.

"Anger is simply just 'I'm afraid, and I don't wanna show it,'" Campbell said.

Many Black men in particular feel that society's institutions, created to teach and protect them, no longer serve them or have failed them, Campbell said. Because of this, they turn to what he calls "the institution of the streets," which often leads to violence.

This thought process can lead to Black men having distorted perspectives of maturity and negative stigma placed on participation in school, Campbell said. When he was 16, growing up in Little Rock, sitting at the front of the class and answering questions was considered effeminate. Several teens in the crowd nodded as he described the stigma.

Chastity Compton, a senior at Little Rock Central, also expressed frustration with the phenomenon, asking how to draw out the potential of kids who don't feel like participating and getting the most out of their education.

"They don't realize it, but they're very smart," Compton said of her fellow students.

Another topic clouded by stigma is mental health, Humphrey said. When he was a kid, mental illness was a treated like a punchline.

"That's not funny anymore," Humphrey said. "We have so many kids who have some form of mental illness."

Parents, especially Black parents, can default to thinking kids are spoiled or poorly raised when really they are suffering from mental illness, Humphrey said.

"Mental illness cannot be controlled by just telling someone to shut up," Humphrey said.

Jackson, who is Black, highlighted mental illness and the stigma around it in the African American community, placing the weight of confronting the problem on their shoulders.

"We've got to own our own responsibility in this area," Jackson said.

Exchanges between panelists and audience members about anger, retaliation, fear, mental health and stigma frequently came back to the need for mentors to take teenagers under their wing and help them set and meet goals.

Campbell said he had few positive male role models as a teenager, and said that one of the lingering problems is that mentors are concerned about being vulnerable with their mentees, sharing not only the successes but also the failures, fears and flaws that make them human.

"We're afraid to truly relate to them," Campbell said, referring to the mentor-mentee dynamic, "and that's not the responsibility of the child, it's the responsibility of us."

Making connections with positive influences such as teachers was a big part of how White was able to find success in academics, she said, and of course having parents who had her back was crucial.

"[My] parents being involved played a really big part in what I'm doing today," White said.

Several audience members stepped up to talk about their work as mentors, with nearly all of them sharing that they had been in prison, often for decades.

"We have a job to do, it's our duty," said Michael Cooper, who said he works with teenagers as a mentor after doing stints in state and federal prison. He tries to tell them that "you ain't got to go through what I went through."

Cooper stressed that only positive role models and a change in mindset would keep teenagers from turning to violence when they were insulted or called a name. Several teenagers and even a few younger kids in the crowd nodded in agreement when he described that kids learn to fight anyone who called them a name.

He urged parents to be involved in their kids lives and really know the type of people their children were spending time with.

"You gotta try to grab a little more time with your child," Cooper said.

Campbell acknowledged that even after all the dialogue they had about the problem Thursday, they couldn't expect to reach a whole neighborhood in one night. However, he said, if they could start with just one person -- like the teenager who stepped up to the microphone and was honest and vulnerable about his feelings and the expectation to fight -- they could take a step closer to improving life in the city and raising outcomes for its children.