"We who believe in freedom cannot rest. We who believe in freedom cannot rest."

Women's gospel voices repeatedly sing that refrain in the introductory video to "The Women's Project," an online exhibit that the Arkansas People's History Project launched this spring.

In 1980, women from around the state began coming together to protect women and children as part of a wide-reaching and influential activist organization that would become The Women's Project. Forty-two years later, it's The Women's Project's groundbreaking history and legacy that exhibit co-producers Acadia Roher and Anna Stitt have begun to promote and protect.

Roher is a public historian, and Stitt is a journalist with a background in major podcast production. The two are part of the Arkansas People's History Project, an initiative to "research, document and share the state's resistance narratives," to make Arkansas' activism history accessible to a wider and potentially younger audience.

It started in 2015 when they ran into Suzanne Pharr, a grassroots activist and author with a national reputation. Pharr lived in Arkansas for decades and founded The Women's Project, a statewide multiracial network that tackled racism, sexism, homophobia and economic injustice, most actively in the 1980s and 1990s. Stitt and Roher weren't familiar with the project, but their curiosity was piqued.

"Anna and I started this back in 2017, really because we saw this lack of these stories that were available to others," Roher explains. "... Then we realized there was still this really strong network here.

"Some of the members are in their 80s now. Still friends, still organizing. We started getting curious and asking people about [The Women's Project], then all these stories started coming out, and it was like, 'Whoa.'"

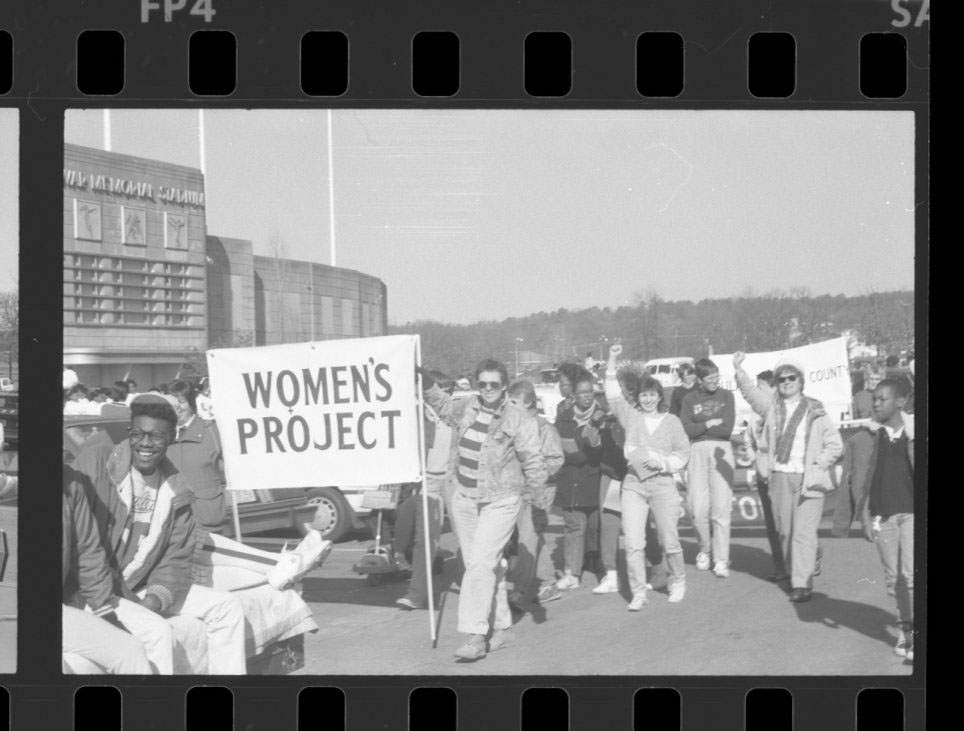

Those stories, told in text, photos, documents, links, videos and audio clips, comprise the new interactive exhibit online at womensprojectstory.org. They tell of women from radically different backgrounds coming together to stand up to the Ku Klux Klan, teach HIV/AIDS education, organize to help battered women, protect children from sexual abuse, fight racism and homophobia, document hate-based homicides and make minority cultural voices more widely available to Arkansans pre-internet.

Pharr explains: "What we had learned from the '70s was seeing that racism, sexism and social injustice are inextricably connected. We couldn't work on one without working on the others. ... This way we could bring the most people together in a way that would really make change."

Stitt and Roher involved The Women's Project's activists at all levels of their research. Stitt says that often outside documentarians or academics will come in "with their own lens" to mine Arkansans' history for their needs. But what emerges is rarely made for or with the people who lived it.

"The narrative control is taken away," she says. "It ends up taking this whole other turn, and people are like, 'That's not true! That's not how we saw that! That's your story, not our story!'"

Your Stories, Not Ours

For this exhibit, Stitt and Roher sought the opposite. Not only could the participants tell their stories in their own voices -- Roher says they often conducted oral histories, story circles and panel discussions with the women via Zoom during the pandemic -- they helped shape what the exhibit would be, choosing the parts of their experiences they felt were most important to share.

An important aspect of the project, Pharr says, was its innovative structure, later modeled by grassroots organizations around the country. The Women's Project representatives traveled across the United States, training others in their methods.

"We thought that in order to make change in the world, you need to have an organization that mirrors that change," Pharr says. To practice the equitable society they sought to create, the Women's Project had an executive director -- initially Pharr -- in name only; all staff were paid the same wage. Rather than have an organization of majority white, urban, heterosexual women, the project prioritized the traditionally underrepresented, ensuring their board and staff makeup had majorities of rural women and women of color.

Likewise, while all women were welcomed, they actively sought to include gay women and those from religious minorities. Without hierarchical structure for decision-making, they relied on group discussion to reach consensus. And rural organizing, something Pharr says is too often neglected by "social justice people" today, was their dominant focus rather than an afterthought.

In an audio clip from the exhibit, Sofia Ali-Khan, a young woman when she got involved, talks about the group's structure. "To be valued that way as a stranger who walked in the door, who didn't look like anybody else in the building, but just had a commitment to the same values -- that sort of way of putting one's ideological commitments into cold cash practice was something I had never seen anybody do before and haven't seen anybody do since."

Stitt says that while imperfect, The Women's Project tried to be intentional about how power and care looked. "Living out this philosophy gave the project staying power, helped them develop a strong, core group with many arms into the wider community."

Damita Marks joined the Women's Project staff in the late 1980s. She couldn't believe she got a job in the Little Rock office. "I was shocked because I was a young, rural Black woman coming from Gurdon, Arkansas, competing with other women who were more conscious [of women's issues] than I was," Marks says. "But my compassion grew to look at women differently. It increased my strength and awareness."

The Women's Project also founded the Women's Watchcare Network, a key element that they trained groups across the country to implement.

Witnesses To History

Initially focused on gender-based violence against women, The Women's Project's growth coincided with another rise of the Klan, which had a compound and training center in Harrison. Black people and communities were being attacked, churches burned. "We said, 'Well, who's monitoring them?' We looked around, and there was nobody. So, we took it on," Pharr says.

The Women's Project created a monitoring program to track activity in Arkansas by the Klan and other hate groups, showing up to protest any pre-announced events. "But what people kept saying to us was, 'This far-right violence is terrible, but what's way worse is the everyday violence,'" Pharr says.

"We decided we would record best we could any violence that was occurring against people of color, against women, against queers, against religious minorities. But in the end we had to limit it to murders. There was just too much violence to keep up with."

Although they were not affiliated, Pharr says the United Methodist Women's groups nationally and locally supported The Women's Project with funds from its earliest days. To track violence statewide, Pharr asked for help. "We'd ask the United Methodist Women in different communities to create small groups that would monitor each of those areas: racism, sexism, anti-gay violence, and expand those networks wherever they could."

Methodists and other Arkansas women clipped and sent to the Women's Project any local news stories of violence toward minorities. The rule was it had to have been reported in print to be recorded, Pharr says. "We knew we wouldn't be believed if these events were not documented somewhere; there were so many clippings." Using any published details to tell the stories, they chronicled each murder in their newsletter, Transformation. (These newsletters can be read online through the exhibit's Resources page.)

Clipping news accounts empowered the volunteers. Pharr says in the face of widespread violence, it was something they could do, even if they didn't know how or when it would be used. "We kept saying to ourselves, 'Even if nothing else comes out of this, we will have stood as witness to this time in Arkansas.'"

As different kinds of women joined the project to work on their own particular focus -- gender-based violence, HIV/AIDS education, homophobia, racism, etc. -- they were exposed to people and perspectives different than they'd known. And they began to learn from each other.

Pharr says growing that mutual respect and understanding was built into the mission. "We knew if they would tell their stories in these small groups, people would begin to understand we are awfully alike," she explains. "We believed greatly in stories."

An audio clip of member Kelly Mitchell-Clark in the exhibit speaks to this personal growth. "When I arrived at the Women's Project, my voice, my understanding of race was very clear. I was raised that way. ... I felt a lived experience. But being at the Women's Project meant I had to overlay those, had to stretch myself, had to understand more about gender and sexism and homophobia. And these were new to me."

The featured voice of another member, Janet Perkins: "I didn't know what homophobia [was], but I was willing to learn. ... And that was one of the commitments that we all had to make, is that you can't just fight for your own issue."

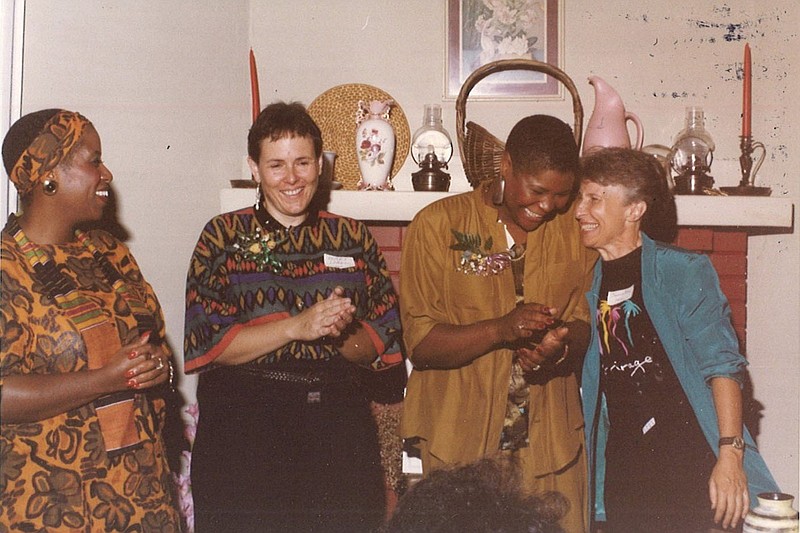

Marks says the women formed real connections. "The women, we groomed each other, we pampered each other. When we were doing good, we stroked each other. When things weren't doing good, we comforted each other. I loved that," Marks says.

It's something she's carried forward in her life: mentoring younger women. Marks' friend and protege, Carolyn Jefferson, grew from a young certified nursing assistant from Helena with big dreams 14 years ago to being a surgical and oncology nurse and owning a medical staffing agency. Both women say they credit the experience and confidence Marks gained from the project with helping propel their growth.

"Everything I wanted to achieve, Damita has helped me do," Jefferson says, "by encouraging and believing in me."

"I think it is so important," Marks says, "to bring a young woman with me to hand off the baton of this work. If I can be a power to help someone -- all of this comes from the Women's Project validating who I am."

The Exhibit

The interactive online exhibit was created with financial support from the Arkansas Humanities Council, Black History Commission of Arkansas, Highlander Research and Education Center and Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation.

For the exhibit, Roher, Stitt and others worked to find photos, documents and videos. The site links to documentation and related materials and includes a Resources page with a discussion guide for educators and other visitors.

Tracking down multimedia from that time was made more difficult by the fact that the Women's Project rarely focused on documenting the project itself. "We didn't seek publicity in the way people do now," Pharr explains. "It didn't occur to us to take pictures of ourselves when we were standing against the Klan and marching in song."

Roher and Stitt led the project, but they credit extensive support by the state's history community and the Women's Project members with making the exhibit possible. They say it's the Arkansas People's History Project's first major project, but not its last.

"As a group, we are very happy with the exhibit, and we think they have done a magnificent job of representing who we were," Pharr says. "We think it also is a gift to other people who are doing social justice work."

Pharr, 83 and once again living in Little Rock, is still one of those people. "Oh, I'm very active," she says. "I don't believe in social justice people retiring."

Marks understands that. "Each one of us that was in the Women's Project, we have a connection to it still. Our passions are still there. It's not like you look at it and say, 'Oh, I used to do so and so.' It's still in you. You still do it.

"I take my hat off to the young women for doing this, revitalizing our work and bringing it back up to the forefront so someone else can pick it up," Marks continues. "That's the whole thing about a 'movement.' Once you've been 'moved,' you're 'meant' to give it to someone else."

Suzanne Pharr and Damita Jo Marks, former board members of the Women's Project, look at a framed cover of the State Press which features the Women's Project Board and a copy of the Women's Watchwork Network Logs on 04/28, 2022 at the Little Rock home of Suzanne Pharr. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Cary Jenkins)

Suzanne Pharr and Damita Jo Marks, former board members of the Women's Project, look at a framed cover of the State Press which features the Women's Project Board and a copy of the Women's Watchwork Network Logs on 04/28, 2022 at the Little Rock home of Suzanne Pharr. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Cary Jenkins) Suzanne Pharr and Damita Jo Marks, former board members of the Women's Project, look at a framed cover of the State Press which features the Women's Project Board and a copy of the Women's Watchwork Network Logs on 04/28, 2022 at the Little Rock home of Suzanne Pharr. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Cary Jenkins)

Suzanne Pharr and Damita Jo Marks, former board members of the Women's Project, look at a framed cover of the State Press which features the Women's Project Board and a copy of the Women's Watchwork Network Logs on 04/28, 2022 at the Little Rock home of Suzanne Pharr. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Cary Jenkins)