Moises Chan was once a member of the Belize Senate, a vice president of his country's council of churches and pastor of St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church in Belize City, the nation's capital.

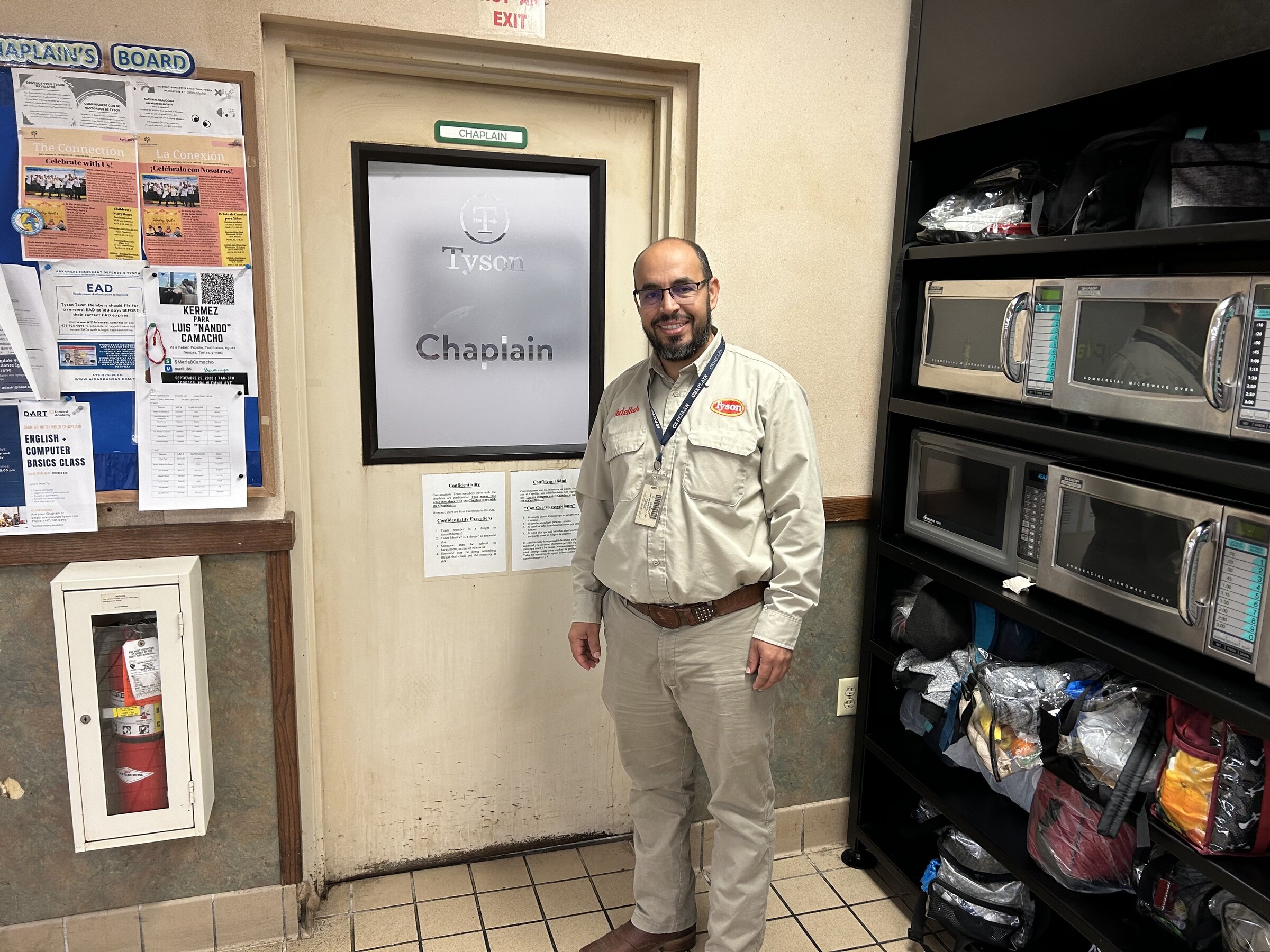

These days, he's a chaplain for Tyson Foods, working at the company's Berry Street poultry facility in Springdale, roughly four miles north of its corporate headquarters.

Chan, 69, works alongside Abdellah Essalki, an Imam originally from Morocco.

They are two of Tyson's roughly 100 chaplains, a group that includes Protestants, Catholics, Muslims and at least one member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Most of them traveled to Springdale recently to receive annual training and to have fellowship with one another.

Chan, who also serves as parish associate at First Presbyterian Church in Springdale, has been a Tyson chaplain since 2015.

He visits employees and their family members in the hospital and provides guidance to recent immigrants who are confronted with a new language and a new culture.

He provides comfort to those coping with grief or loss.

In one instance, he says, he agreed to attend an educational class with an elderly team member who was unwilling to go alone.

"He was embarrassed that he does not know how to read or write," Chan says.

"I said, 'Let's learn little by little, one word at a time,'" he recalls.

"When he left, he could sign his name," Chan says. "That is the joy that we find in serving Tyson's at these plants."

There aren't many Presbyterians processing chickens on Berry Street -- or Muslims, either.

That doesn't prevent the chaplains from serving those around them, they say.

"It is no barrier," says Essalki, a Tyson chaplain since 2017.

"You're taking care of people," he says. "You're with people and engaging them and deeply understanding them, deeply responding to their needs."

In its purpose and values statement, Tyson says: "We strive to honor God and be respectful of each other, our customers, and other stakeholders."

There's no religious test to work at Tyson.

Today, Tyson Foods has nearly 140,000 team members and reported $47 billion in total sales during fiscal 2021.

"We are not a faith-based company. We say that we're a faith-friendly company, which means we're inclusive of whatever faith, or lack thereof, that people bring to work," says Kevin Scherer, director of chaplain services.

Launched in 2000, Tyson's chaplaincy program has expanded over the years.

"The company started with 11 part-time chaplains in eight states," Scherer says. "Today we have around 100 chaplains in 25 states and 85% of them are full time."

They're not confined to the Bible Belt; they serve in red states and blue states.

"We have them everywhere from the West Coast in Pasco, Wash., to the east coast in Temperance, Va., and everywhere in between," Scherer says.

It's a well-educated cohort.

"Seventy-five percent of our chaplains have a master's degree or higher," Scherer says.

'PROVIDE SPIRITUAL CARE'

They aren't paid to preach. They are there, Tyson says, to "provide compassionate, spiritual care that explores team members' diverse belief and value systems, honors their experiences, and empowers them with resources to enhance function and well-being."

"When chaplaincy is done right, [the] chaplain's own faith orientation is invisible," Scherer says. "A good chaplain can minister to anyone."

Employer-chaplain conversations are confidential "except for those that reveal risk of injury to self, others, or the business," the company promises.

As a chaplain, Chan says he tries to provide "a listening ear."

"Many times, that's all they need: somebody to hear them," he says. "They need somebody to just listen to their pain, to their hurt, their cries, their needs. And that's all it is. That's the beginning for them, for them to begin to reflect themselves what it is that they're going through."

Others in their lives may be telling them "what to think and how to believe and how to behave and all that," Chan says.

As chaplains, "we don't need to tell them. They will figure it out. They're smart enough to understand their own needs and their own problems, the issues that they're facing," he says.

THE LAST COLONY

When Chan was growing up, Belize was known as British Honduras. Roughly the size of New Jersey, it was the last British Crown Colony on the continent.

The colonists taught Chan English and shared their faith.

A faithful Presbyterian, he eventually received a scholarship to attend Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Miss., where he received a Master's of Divinity, the first of three graduate degrees.

After years of service, he and his wife, an American citizen, decided to return to the United States, eventually leading a Reformed Presbyterian congregation in the Yell County hamlet of Havana.

Since coming to Arkansas, he has made ministry to Hispanics a priority. He is currently director of Ministerio a la Vecindad (Ministry Neighborhood), which provides services to those in need.

Pastorally, he feels a special connection to those who have immigrated to the United States from Latin America, he says.

He speaks not only Spanish but a Mayan language, as well.

"We know the transition that they're making as they come to this country. It is not easy. ... We know that," he says. "That's why we are able to sit with them and stand with them and walk with them."

Like Chan, Essalki knows what it's like to leave home and start anew. He immigrated to this country in 2004 to work in an Islamic center in Mississippi.

"At that time, I didn't even speak English," he says.

TO MAKE ENDS MEET

Essalki worked a second job to make ends meet. Whenever possible, he attended English classes.

In 2010, he was hired as youth director for an Islamic center in Fort Smith. Ten years after arriving in the United States, he earned a Master's of Education degree from the University of Arkansas.

In addition to his degree in Islamic law (sharia) from Al Quaraouiyin in Morocco, he now possesses a juris doctorate from the University of Arkansas School of Law, and serves as Imam at the Islamic Center of Northwest Arkansas.

At the center, Essalki leads Friday prayers and teaches the tenets of Islam.

At Tyson's, he focuses on what he calls "genuine listening."

When someone needs pastoral care, "you're not listening to reply to them, but ... [you're] listening in order to understand them deeply," he says.

Rather than trying to convert people, "we come alongside with them, and we walk their walk," he says.