- "Everything is recycled and rerun and comes back — first as camp, later as classic."

- — the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, on Wilco's "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot," April 2002

It is not Wilco's fault we live in the time we live in, this time of instant gratification and auto-tune. If we're being fair, maybe pop music these days is what pop music should have always been, a sonic wallpaper we plaster over what Walker Percy called the "everyday" of our existence.

Sure, people still care and artists still "art," but these days it seems silly to wish for an album that might change the world. Albums aren't the point anymore, and though it feels like a churlish-old-man thing to say, neither is the music.

The music has always been — at least since they figured out how to trap, kill and commodify it — more lifestyle product than anything else. While we can argue that rock 'n' roll is more cultural practice than musical genre, once the marketers get hold of anything they can distill down to a cool vibe, all the potential for authentic experience slides to the periphery.

Our economy is big enough to sustain a few genuine outsider artists like Dan Bern and Terry Allen and dozens if not hundreds of midlevel acts like Lucinda Williams and Iris DeMent, but those artists have to work hard at it, to make money by, as James McMurtry puts it, selling beer to nightclub patrons rather than by selling records.

Who buys records anymore, anyway? (Ironically, judging from personal experience, old rock critics — who never paid for albums in the '70s, '80s or '90s — might account for a sizable amount of the market.)

We've arrived at the 20th anniversary of the release of "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot," Wilco's fourth and probably best album, though like almost everyone else, I lost the thread shortly thereafter. While I've listened to all and enjoyed most of the records Wilco has put out in the past 20 years, the truth is they run together on me and I suspect on the band too. "Wilco Schmilco" they called one of them.

Still, they were at one point my favorite American band — they filled the gap between Tom Petty's Heartbreakers (R.E.M. might have held the title for a year or two) and the Drive-By Truckers. I still love "A.M.," "Being There," "Summerteeth" and "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot."

I enjoy a lot of Jeff Tweedy's work and would love to catch his acoustic solo set sometime. I feel kindly toward Wilco. It's just that every album since 2004's "A Ghost Is Born" has gone straight to my digital library. I don't listen the way I used to.

Something crucial went out of the band in 2001 when they jettisoned the late Jay Bennett, who for a time competed with Tweedy to be the band's chief creative engine. If you've seen Sam Jones' brilliant 16mm black-and-white documentary "I Am Trying to Break Your Heart, " a film about the band and their struggles completing "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot," you probably understand why the break was necessary.

Bennett and Tweedy were incompatible as creative partners. Bennett was an overbearing obsessive; Tweedy was a conflict-averse migraine sufferer. Continuing to work with Bennett could have killed Tweedy.

Not getting to work with Tweedy might have killed Bennett, who died of an accidental fentanyl overdose in 2009. (Gorman Bechard and Fred Uhter's documentary "Where are you, Jay Bennett?," released earlier this year, in part grew out of the desire to rehabilitate Bennett's image, which the filmmakers believed had been unfairly damaged by Jones' film.)

Still, for whatever reason, the Wilco I love best is the Tweedy/Bennett version, which had its ultimate expression in "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot."

I AM TRYING TO BREAK YOUR HEART

One of the markers about how times have changed is that when "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" was released in April 2002, this newspaper ran a 2,000-word review. It's hard to imagine an album by any artist — Beyonce, Lizzo, Billie Eilish — commanding that sort of attention in a general interest publication today.

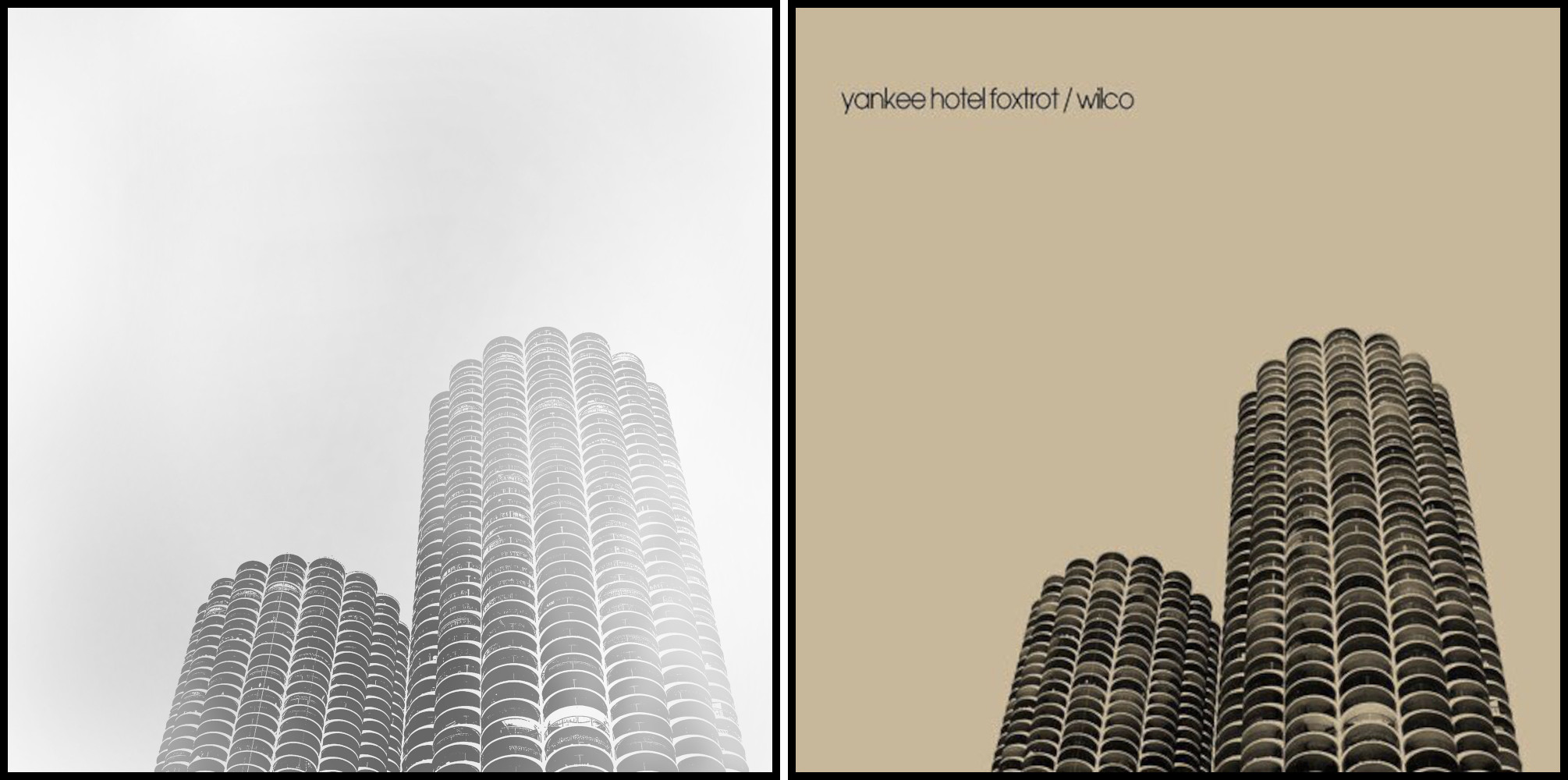

The cover of new Wilco box set (left) and the original 2001 cover of the album. Even before it was officially released, "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" was a digital hit.

The cover of new Wilco box set (left) and the original 2001 cover of the album. Even before it was officially released, "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" was a digital hit.

When the band presented the finished album to its record company Reprise — a division of Warner Music Group that had been founded by Frank Sinatra in 1960 (Sinatra's role at Reprise led to his nickname "The Chairman of the Board") — the executives didn't know what to make of it. They deemed it an unreleaseable career-ender.

And since none of the previous Wilco albums had performed well commercially, they dropped the band. (This is ironic since Warner had, in the '60s and '70s, a reputation for nurturing and protecting the artists they signed. Reprise — home to Neil Young, Jimi Hendrix and Joni Mitchell among others — was considered especially artist-centric and committed to taking the long view of a career.)

But Wilco had fulfilled its Reprise contract simply by presenting the record. The members had essentially been paid for it, so when the label dropped them, they began streaming it for free on their website on Sept. 18, 2001. That drew attention to the album and raised the band's profile to such an extent that, in November, Nonesuch Records, another imprint of Warner Music Group, offered them a new record contract, with "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" as the first in the deal.

(It's often said Wilco was paid twice for the album by Warner Music Group, but what really happened was that the band acquired the rights from Reprise after the label declined to release the album by paying Reprise $50,000. Then Nonesuch came in with a new deal.)

RESERVATIONS

For its 20th anniversary, "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" has been remastered and reissued in expanded forms, including a "Super Deluxe" version that "lists" for $249.98 (shop around and you can probably find it for $100 cheaper) and consists of 11 vinyl albums and one CD that includes 82 previously unreleased tracks such as demos, drafts, and instrumentals that chart the making of the album.

There's a 2002 concert recording and a September 2001 radio performance and an interview with Tweedy, drummer Glenn Kotche and Jim O'Rourke, who mixed the acclaimed 2002 album; an in-depth essay by journalist Bob Mehr; and previously unseen photos of the band members making the album in their Chicago studio The Loft. (For the "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" recording, Wilco's lineup consisted of songwriters Tweedy and Bennett on vocals and guitar, bassist John Stirratt, drummer Kotche, and multi-instrumentalist Leroy Bach. Craig Christiansen, Ken Coomer, Jessy Greene, Fred Lonberg-Holm and O'Rourke also made significant contributions.)

There are less expensive options, including an eight-CD "Super Deluxe" version that retails for $119 and a budget two-CD "expanded" version ($19.98). As always, the music is probably the most obtainable part of the equation — if all you want to do is hear it, most (though not all, not yet) of it is available on streaming services. What you're paying for is a displayable fetish item, tangible evidence of your good taste.

Nobody buys a cool leather jacket just to stay warm.

BEAUTIFUL AND STONED

As for the imminently obtainable part of the package, it's always difficult to write about anything as transitive and super-lingual as music; the insufficiency of language to aptly describe the emotion that can be wrung from a plaintive chord decaying in the air is profound.

Musicians stir the air and make us feel loss or joy. About the last thing one needs is to have his fonts of bliss explained to him. On this level, writing about music — especially pop music — is stupid.

But when I first heard "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot," I was struck by the fusion of future sound-archival memory the band was able to conjure up from the opening notes of "I Am Trying to Break Your Heart."

Here it comes, some airy techno fuzz, the clack of drumsticks, a few pregnant bass notes, a tinkle of Sgt. Peppery percussion, some keyboard noises, an oddly insistent acoustic guitar, then the singer, Tweedy, here a Ray Davies sound-alike, starts in:

- I am an American aquarium drinker

- I assassin down the avenue

- I'm hiding out In the big city blinkin'

- What was I thinkin'

- When I let go of you?

"I Am Trying to Break Your Heart" is an extraordinary song, not because of its melody line or its vague lyrics that nod to E.E. Cummings and Bob Dylan and even borrow an image from an old King Crimson album title, but because of the way it starts out so spare and disparate and somehow coheres into a genuinely affecting pop song, a magpie's nest studded with junk and treasures from decades of old television shows, radio hits and cult classics culled from older siblings' record collections.

That's how the album is: No influence is too low to be acknowledged, no aspiration too high. Some people will call albums and bands like this "pretentious," but that always happens when someone who plays a guitar and tries to sell records actually means to make something like art.

"Hotel Yankee Foxtrot" marks Wilco's transition from corn-fed American roots rockers (informed by the aforementioned Heartbreakers and R.E.M.) into an art rock outfit along the lines of then-ascendant Radiohead. You can still hear what people call alt-country/Americana in the songs (Tweedy's chord structures are squarely in the mainstream of the blues-rock-folk tradition, no matter how jazzy and spacey the songs run).

What's genuinely hard to understand is how the Reprise executives could have failed to realize how commercial and poppy — how listenable — "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" is, even if they couldn't imagine what record store bin it might be filed under.

But these days, when record stores are rarer than museums, we're used to re-imagined and re-combined, genre-mixing sounds. Maybe 20 years ago we saw brighter lines between genres and we needed someone like Tweedy (and/or Bennett) to point out the possibilities.

About the best argument I could make against "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot" is that it's a "tasteful" and obviously ambitious album, an anomaly when it comes to great rock 'n' roll albums that generally lean more to the brilliant, sloppy accidents that critic Manny Farber referred to as "termite art" than the planned, self-conscious "elephant art" produced by those who see themselves as "artists."

Wilco’s John Stirratt, Leroy Bach, Jeff Tweedy and Glenn Kotche (circa 2001, minus Jay Bennett) (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) CULTURE HEROES

Wilco’s John Stirratt, Leroy Bach, Jeff Tweedy and Glenn Kotche (circa 2001, minus Jay Bennett) (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) CULTURE HEROES

The best rock 'n' roll is antithetical to good taste. All those trashy garage bands from the '60s are culture heroes, they're releasing boxed sets of their inexpert slash-and-scream records, and it all sounds cool now. Remember how weirdly appropriate it was when the Replacements covered KISS' "Black Diamond" on "Let It Be" (a 1984 album whose very title invited everyone to notice how un-Beatlesque, how amateurish and sloppy and inspired they were)? KISS fans probably beat up the Replacements in high school.

Another thing that happened in 1984 was that Tweedy and Jay Farrar and Mike Heidorn, another guy who went to their high school, started a band called Uncle Tupelo. They meant for it to be a punk band and were hoping it would sound like Dinosaur Jr. or maybe how the Sex Pistols would have sounded if they'd grown up in the Nowhere that was Belleville, Ill. But they didn't sound like the Sex Pistols or Dinosaur Jr. They sounded like a bunch of hicks; they got twangy in their voices and in their instruments' heavier strings.

Maybe it was their parents' records, all that countrypolitan pop, those Marty Robbins gunfighter ballads and trail songs, Miz Loretta singing about the pill and being stuck in Topeka, and the Eagles stabbing beasts with their steely knives.

Or blame it on an accident of birth, the fact they were small-town, small-time kids who thought it would be funny to cover the Stooges' "I Wanna Be Your Dog" with Jethro Bodine accents.

Before you know it they got credit for doing something they didn't do, which was invent alt-country. Uncle Tupelo was a mighty good band by the time it started releasing records, but probably not as great as it seems in retrospect, which is mostly the way it has been heard.

Uncle Tupelo was not as good as Wilco. It probably wasn't as good as Son Volt. UT didn't start alt-country any more than Elvis Costello started it when he released "Almost Blue" (produced by Nashville hack Billy Sherrill) in 1977. Better to credit Emmylou Harris or Gram Parsons, or the Byrds' "Sweetheart of the Rodeo" or even Elvis Presley. But looking for the roots of roots music is as dull as it is useless.

Rock 'n' roll differs from country music primarily in that while country targets an adult audience, rock is for the kids. We could even argue that rock 'n' roll is less a musical genre than an attitude. But rock was a byproduct of America's post-war invention of the teenager as a consumer demographic. Rock 'n' roll was created so that kids would have something to spend their allowances on.

So from the moment that rock 'n' roll started nudging toward an adult audience, before Bob Dylan decided to take it all so seriously, you had the beginning of what some of us now call alt-country — rock music, big beat, simple-to-play pop music for adults. The rules are there are no rules, you can pull from whatever influenced you, you can steal and re-invent and work the personal until it becomes universal.

If you're the kind of person who reads essays about rock 'n' roll records, you come back to the artists you believe genuinely care about the things they're singing about — not just their careers. And you have to trust a band that, like Uncle Tupelo, could reach back to an old Carter Family song like "No Depression" and turn it into something like a movement. You've got to trust a band like Wilco who can put out a record like "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot."

You've got to wonder why you care about stuff like this, but the only real answer is that it moves you — probably because you're as much a part of it as it is a part of you, and you can nod in agreement as Tweedy, on another song called "Heavy Metal Drummer" drops into that soft Kinksy voice again, and murmurs:

- I miss the innocence I've known

- Playing KISS covers, beautiful and stoned

At the time, it felt like an evocation of nostalgia. Now it feels like a benediction. Innocence is only noted in its absence.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com