FAYETTEVILLE -- Stories "are how we learn, how we share about ourselves, and what we value," says author Angeline Boulley, an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

Stories "help explain who we are and how we got here," added Boulley, author of "Firekeeper's Daughter," which was No. 1 on The New York Times best-seller list in the Young Adult Hardcover category in April 2021. "Story is a living force that finds its way when it sees an opening."

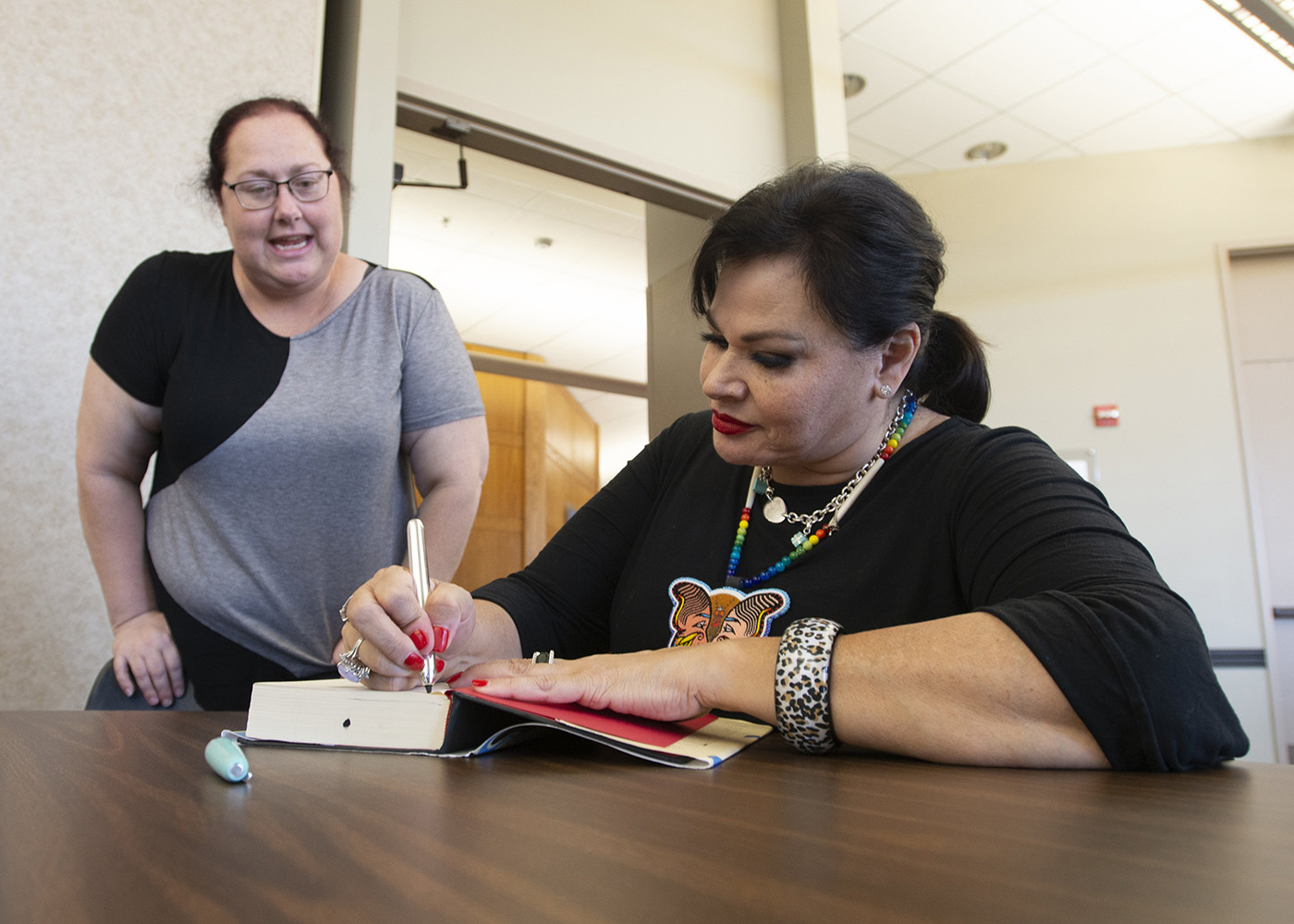

Boulley was joined by other area indigenous authors and artists for a panel discussion Thursday at the Arkansas Union on the campus of the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Boulley also delivered a lecture Wednesday night at the Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History.

"I wanted to tell a truthful story, so I had to include unpleasant truths about our community, but also joyful things, and the way our community finds healing, [because] we are more than our trauma," said Boulley, whose follow-up to "Firekeeper's Daughter" is scheduled for a May 2023 release. Non-native writers too often spot only the "surface trauma and tragedy" in indigenous communities, but "that is not what I see."

"My community has as much joy, humor, and fun as anything else," she said. "I write about trauma, but I didn't write a tragedy."

Likewise, author Andrea L. Rogers balances "the difficult things with things that are empowering" in her writing, she said. She wants to "encourage young people to take responsibility for themselves and do what they need to" in order to survive.

She guards against misogyny and stereotypes in her writing, because she noticed them in books she read as a child and young adult. Rogers, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, began writing books for children a quarter century ago when she wanted to share books about native people by native people with her daughter, but found a paucity of titles by native authors.

Rogers, currently a Ph.D. student at UA-Fayetteville, felt compelled to write for her child -- and other native children -- to "teach them about us," she said. Indigenous people "are still here, we're not ghosts, we're not gone."

Visual artist Jay Benham often depicts personal experiences in his art, especially his childhood on a reservation, and he aims to draw attention to the lack of resources in native communities that results in "wasted talent," even today, he said. "I try to tell the truth of what is happening, [and] I have an obligation" to tell the stories of his people through art.

Benham, an enrolled member of the Kiowa Tribe who has exhibited in Arizona, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, and is currently a museum educator for Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, finds joy in envisioning an image, then executing it on canvas. "I want to keep a record of who we were, and who we are," he said.

Benham, Boulley, and Rogers all adroitly balance uncomfortable truths with optimism in their work, said Toni Jensen, who is Metis, an author who teaches at UA-Fayetteville and the Institute of American Indian Arts, and led Thursday's panel discussion. There's "an ethos of responsibility" to their culture in their art, too.

"Everyone has a story, [but] when you lose someone, you lose that story," said Rogers, whose book, "Mary and the Trail of Tears: A Cherokee Removal Survival Story," was named a National Public Radio Best Book of 2020 in the Children's Literature category. "It took me until my late 40s to have a true understanding and appreciation of my Cherokee culture."

Some native stories, passed down through generations, are "fixed," but others are "fluid, [which] says something about us and our adaptation to survive," Boulley said. In "Firekeeper's Daughter," for example, Boulley's protagonist "walks between worlds, [and] it's a story about identity, at heart, dressed up in a thriller."

"Firekeeper's Daughter," Boulley's debut novel, received the Walter Dean Myers Award for Outstanding Children's Literature, and has been a selection of numerous book clubs, including "A Reese Witherspoon x Hello Sunshine Book Club YA Pick."

Boulley, former director of the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education, writes about her Ojibwe community in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and her novel follows the life experiences of a young, biracial, unenrolled tribal member, Daunis Fontaine, as she goes undercover for law enforcement to investigate a deadly drug in her community.

Fontaine's experience is informed by Boulley's own, as she has one native parent -- her father is Ojibwe -- and a non-native mother, she said. She also didn't grow up on a reservation but "went back every summer," thereby maintaining her connection to that world.

Fiction is an ideal format for Rogers, who "was always making up stories," dating back to her childhood.

"Fiction is a great place where we can lie and not get in trouble," she said to hearty laughter from the audience. "In fact, you get paid for it, sometimes."