JACKSON, Miss. -- A former director of Mississippi's welfare agency pleaded guilty Thursday to federal and state charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. -- part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.

In federal court, John Davis pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy and one count of theft from programs receiving federal funds. In state court a short time later, he pleaded guilty to five counts of conspiracy and 13 counts of fraud against the government.

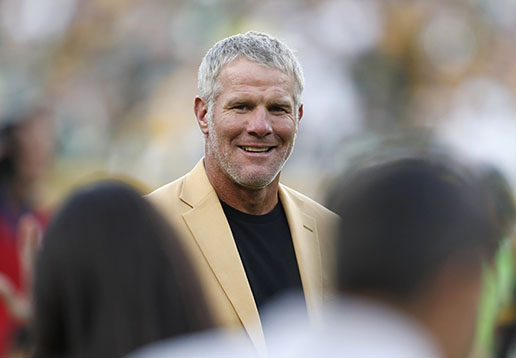

Davis, 54, was an influential figure in a scandal that has produced criminal charges against several people, including pro wrestler Ted DiBiase, known as the "Million Dollar Man." The scandal also has raised questions about retired NFL quarterback Brett Favre and former Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant.

As leader of the Mississippi Department of Human Services, Davis had direct control of federal funds that were channeled to pet projects such as a new volleyball arena at the university where Favre's daughter played the sport.

In state court Thursday, Judge Adrienne Wooten asked Davis to explain why he had allowed the department to squander money for the needy.

"You were entrusted to do good by those that we consider 'the least of those,'" Wooten said. "This court is very disappointed."

The state court charges were mostly tied to welfare money spent on one of Ted DiBiase's sons, Brett DiBiase, who was also a pro wrestler. The spending included $160,000 for drug rehabilitation in Malibu, Calif.; a $250,000 salary for a job he was not qualified to do; $48,000 for him to teach Department of Human Services employees how to identify possible drug use by people seeking help from the agency; $8,000 for him to stay at an upscale hotel in New Orleans; and more than $1,000 for first-class airfare for Davis to fly to Malibu to see Brett DiBiase.

In response to one of many questions from Wooten, Davis said Brett DiBiase was his friend. Davis also said he used "very, very bad judgment" in spending public money.

"I shouldn't have done it," Davis said.

Wooten gave Davis a 90-year sentence with 58 of those suspended and 32 to serve. She put Davis on house arrest until his federal sentencing, set for Feb. 2. He faces up to 15 years on the federal charges.

U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves said he hopes Davis makes better decisions from now on.

"I look forward to hoping that this portion of your life is behind you," Reeves said.

EX-FOOTBALL PLAYERS

Mississippi claims that Marcus Dupree, a former high school football phenom and professional running back, who was paid to act as a celebrity endorser and motivational speaker, did not perform any contractual services toward the $371,000 he received to purchase and live in a sprawling residence with a swimming pool and adjacent horse pastures in a gated community.

Favre, who earned more than $140 million in his Hall of Fame career, was paid $1.1 million for speeches he never gave, the suit said. He also orchestrated more than $2 million in government funds being channeled to a biotechnology startup in which he had invested, according to the suit.

The two ex-players, along with Davis, have been charged with crimes and all have denied wrongdoing.

"The profiteering off the poor is ongoing," said Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss. He added, "It is like Robin Hood in reverse -- you take from the poor and give to the rich."

The accusations about fraudulent grants were all laid out in the lawsuit filed in May against 38 individuals and organizations, which sought the repayment of more than $24 million. Rather than helping the poor, the federal welfare program known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, appeared to become a slush fund for pet projects and personal gain.

The state alleges that the money was siphoned off for services that were often never provided and, in any case, would have failed to meet both federal and state regulations governing their dispersal. The case follows a state audit released in May 2020 suggesting that as much as $94 million of TANF funds might have gone astray.

Six people were arrested in February 2020 on charges of misusing public funds in what the state auditor, Shad White, has described as one of the largest public corruption cases in Mississippi's history. Most of them have pleaded guilty; Jody Owens II, the Hinds County district attorney, said a joint inquiry by federal and state investigators could produce charges against more people.

Lawyers for the senior DiBiase and Dupree did not respond to requests for comment. Michael Dawkins, the lawyer representing DiBiase and his Heart of David Ministries, said in court papers that his clients had acted legally.

After the charges first emerged, a lawyer for Dupree, J. Matthew Eichelberger, released a letter saying his client had earned the money.

Bud Holmes, Favre's lawyer, did not return a request for comment. Both he and Favre have said repeatedly that the football legend was not aware that the funds came from a federal welfare program.

When it comes to basic assistance, Mississippi ranks 47th among U.S. states in the amount of money it spends, said Aditi Shrivastava, a senior policy analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C. Figures compiled by the center indicate that the median maximum benefit nationally, which few people are paid, was $498 monthly in July 2021, compared with $260 in Mississippi.

Experts said the fraud was rooted in changes enacted in such programs in 1996, when cash benefits paid to poor families were replaced by block grants issued to states. They are supposed to distribute the money according to four federal guidelines that emphasize moving poor families toward steady employment, but in practice, states and governors are given broad leeway.

Ironically, the Mississippi Legislature also added a fifth guideline: "to prevent fraud and abuse." That was directed at recipients of the aid, but the state now alleges that the malefactors turned out to include the public officials running the program.

Nancy New and her son Zach, who ran a nonprofit educational organization called the Mississippi Community Education Center, pleaded guilty last spring to charges of misusing TANF funds.

The text messages that were revealed in court documents suggested that Bryant, working with New, helped Favre obtain federal money for a state-of-the-art volleyball facility to be built at Bryant and Favre's alma mater, the University of Southern Mississippi, where Favre's daughter played the sport.

"Can we help him with his project?" Bryant wrote in a July 2019 text to New, noting that he had just talked to Favre.

In 2020, the state auditor's report said the university received $5 million for a bogus lease to use all its athletic facilities -- including the volleyball center, which was not yet built -- for programs for the poor.

The money, paid by the Mississippi Department of Human Services via the News' nonprofit organization, actually went toward construction, the audit said. Last April, Zach New pleaded guilty to transferring $4 million from TANF funds, which the federal government bars from using for "brick and mortar" projects, to the university.

The texts released last week seemed to indicate that the $1.1 million welfare contract to promote the center's programs -- work that was never performed -- was another way to divert money to the stadium.

In the August 2017 text conversation about concealing the source of the money meant for the facility, Nancy New assured Favre that she understood he was "uneasy," but that that kind of information was never publicized. The next day, she wrote: "Wow, just got off the phone with Phil Bryant! He is on board with us! We will get this done!"

William Quin II, a lawyer for Bryant, said the text messages did not support the argument that the governor had encouraged and coached Favre and state officials on how to obtain the grant. "The allegation is patently false," he said in an emailed statement, dismissing the text messages as "cherry-picked." Bryant has not been charged with any wrongdoing.

The volleyball stadium was not actually part of the lawsuit. Last July, after J. Brad Pigott, a former U.S. attorney hired by the state to help recoup the lost millions, began subpoenaing information about what had happened at the university, he was dismissed. Favre has repaid the state $1.1 million -- although the state auditor has said he still owes $228,000 in interest.

Organizations that help the poor have long worried that block grants awarded by governors can be an invitation for abuse, said Oleta Garrett Fitzgerald, director of the southern regional office of the Children's Defense Fund.

"There was a danger of that money becoming a slush fund well before this debacle," she said.

In Mississippi, she and others said, the problem is compounded by the fact that the state's Republican governors and legislatures of recent years have been ideologically opposed to government programs designed to help the poor. "They probably thought that it was funny to be using money that was supposed to go -- in their minds -- to people who didn't deserve it," she said of the accused officials.

Mississippi is one of 12 states that has refused to expand Medicaid and has regularly turned down federal money meant to improve medical treatment, housing and child care, among other issues, Thompson noted. At the end of 2020, Mississippi had $47 million in unspent TANF funds, Shrivastava said.

At the University of Southern Mississippi, faculty members say the school prides itself in admitting first-generation students from the kind of families the money was meant to help. "No one is very happy about it," Denis Wiesenburg, faculty senate president and professor of marine science, said of the recent unwanted attention. "We recognize that it has tarnished the reputation of the university."

The scandal has seeped out over years now, largely because of dogged reporting by the Mississippi Today website. But that does not dull the anger of those most affected.

Carol Burnett, executive director of the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative, a nonprofit organization, said people were appalled that tens of millions of dollars that should have gone toward initiatives such as improved public transportation or child care for the working poor were apparently handed out to rich political cronies instead. "They see this money that is intended to help people like them that is so misused and redirected to people who do not need help," she said. "It is infuriating."

Information for this article was contributed by Emily Wagster Pettus of The Associated Press and by Neil MacFarquhar of The New York Times.

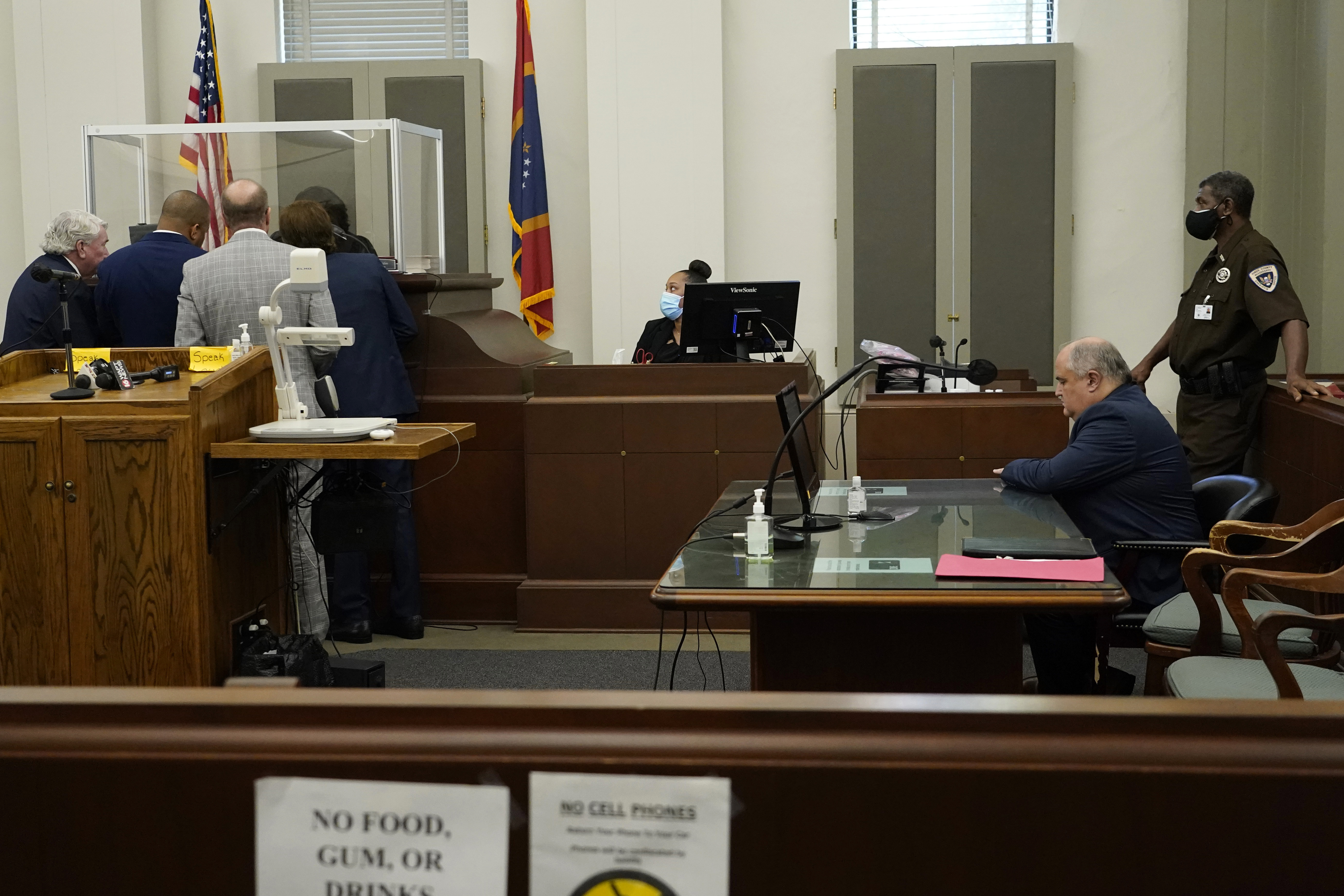

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services, sits to the right side while the state's and his defense attorneys confer with Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten in Jackson, Miss. on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services, sits to the right side while the state's and his defense attorneys confer with Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten in Jackson, Miss. on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services confers with defense attorneys Merrida Coxwell, right, and Charles Mullins, left, in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services confers with defense attorneys Merrida Coxwell, right, and Charles Mullins, left, in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services and defense attorney Merrida Coxwell, center, is admonished by Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten, right, in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services and defense attorney Merrida Coxwell, center, is admonished by Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten, right, in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services left, and his defense attorneys Merrida Coxwell, second from right, and Charles Mullins, listen as state charges are read in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services left, and his defense attorneys Merrida Coxwell, second from right, and Charles Mullins, listen as state charges are read in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten, sits behind her protective barrier as she confers with the state's attorneys and defense attorneys for John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Hinds County Circuit Judge Adrienne Wooten, sits behind her protective barrier as she confers with the state's attorneys and defense attorneys for John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) Hinds County, Miss., District Attorney Jody Owens II (left) and State Auditor Shad White said Thursday outside the Hinds County Courthouse in Jackson that a joint inquiry by federal and state investigators into the state’s welfare scandal could produce charges against more people. (AP/Rogelio V. Solis)

Hinds County, Miss., District Attorney Jody Owens II (left) and State Auditor Shad White said Thursday outside the Hinds County Courthouse in Jackson that a joint inquiry by federal and state investigators into the state’s welfare scandal could produce charges against more people. (AP/Rogelio V. Solis) Then Gov. Phil Bryant speaks about his legacy following a life of public service, Jan. 8, 2020, in his office at the Capitol in Jackson, Miss. Newly revealed text messages show how deeply involved the former Mississippi governor was in directing more than $1 million in welfare money to retired NFL quarterback Brett Favre. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis, File)

Then Gov. Phil Bryant speaks about his legacy following a life of public service, Jan. 8, 2020, in his office at the Capitol in Jackson, Miss. Newly revealed text messages show how deeply involved the former Mississippi governor was in directing more than $1 million in welfare money to retired NFL quarterback Brett Favre. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis, File)