On Nov. 9, 1951, Jim Thorpe, who had been voted “Greatest Athlete of the Half-Century” a year earlier in an Associated Press poll of nearly 400 sportswriters and broadcasters, had a cancerous tumor removed from his lower lip at a hospital in suburban Philadelphia.

The next day, news photographers converged to snap pictures of him in his hospital bed, his lower jaw bandaged. Reports announced he was cheerful despite the announcement made by his third wife, Patsy, that the couple was “broke.”

“Jim has nothing but his name and his memories,” she said. “He has spent money on his own people and has given it away. He has often been exploited.”

Chief among his exploiters may have been Patsy, a former nightclub singer who claimed to have played piano in one of Al Capone’s joints.

After Thorpe was voted “Greatest Athlete,” she stated her goal was to turn that honor into $1 million. She managed her husband’s career and had cobbled together a kind of vaudeville act for him. He would read a poem, tell some jokes, then head for the bar.

She set him a $1,000-plus expenses fee for speaking engagements. She saw him as the host of a national TV show, and cut a deal for him to manage a young American Indian who competed as a pro wrestler under the name of Suni (or Sunny) War Cloud. Thorpe and his charge would walk to the ring together, wearing full headdresses.

She had a public relations job lined up with the National Football League’s Philadelphia Eagles for him.

“I have been determined to get Jim back in the limelight and damned if I haven’t made it,” Patsy wrote to her husband’s oldest daughter, a 30-year-old she’d never met in person. “But I work on it 24 hours a day. I have literally kicked in doors all over the country, and Jim Thorpe will be the greatest thing in the sports world from now on. Of course, you know how lazy he is. I have to dynamite him and ride herd on him constantly. ”

But the oral cancer pretty much put the kibosh on Patsy’s make-a-million campaign. While there were several campaigns to raise money for the Thorpes, including ones organized by the Pittsburgh Pirates and Green Bay Packers, it’s hard to say how much money actually reached the Thorpes. And Thorpe’s sons contended that whatever filtered down to them, well, Patsy probably spent it on herself.

Anyway, within months, the Thorpes were living in a trailer park in Lomita, Calif., near Los Angeles. During a late lunch on March 28, 1953, Jim Thorpe collapsed. It was his third and final heart attack.

Just as New York Yankees great Don Mattingly once admitted he was in the major leagues before he realized Babe Ruth was a historical figure and not some Paul Bunyan-esque myth, most of us probably have a sketchy idea about Thorpe. He was a real man, a great athlete who won two gold medals in track and field at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics (only to have them stripped from him a year later because he’d played a couple of seasons of semi-pro baseball), twice earned all-American honors as a college football star, played six seasons of major league baseball, helped start the National Football League, and barnstormed as a pro basketball player.

He was also an alcoholic, a tragic embodiment of the stereotypical “drunken Indian.” It is easy for us to reduce his story to a few simple lines. All we need do is watch Burt Lancaster as Thorpe in the 1951 film “Jim Thorpe: All American.”

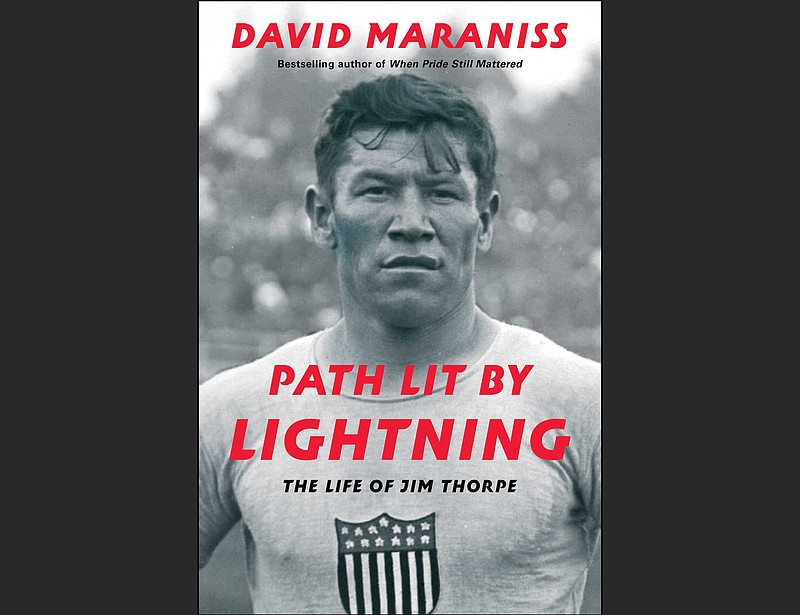

So veteran Washington Post journalist David Maraniss has performed a great service with his detailed, clear-eyed and at times impenetrably sad biography, “Path Lit By Lightning,” which derives its title from a translation of Thorpe’s Sac and Fox Nation name Wa-Tho-Huk.

Maraniss hews to the conventional assumption that Thorpe was largely a victim — chronically patronized, exploited and misused by people and powers he trusted — but resists the temptation to infantilize Thorpe as a simpleton without agency. This Thorpe is a proud and taciturn man, whose reluctance to speak for himself no doubt complicated his life as well as the job of his biographer.

Thorpe didn’t talk or write too much; the only way to attempt to know him is to look at what his friends, associates and family said about him.

That doesn’t mean that “Path Lit By Lightning” isn’t a valuable corrective to the myths surrounding Thorpe — the Pop Warner depicted here is a moral coward and a liar, not a benevolent father figure — only that even after reading it, Thorpe remains an enigma. Because that’s just how some people are.

Thorpe always wanted to be buried back in Oklahoma, but the night before a traditional Sac and Fox burial ceremony, during a tribal feast held to pay tribute to Thorpe’s life and legacy, Patsy swooped in with a hearse and several police officers to carry away the coffin. They took it back to Los Angeles, where a viewing was held.

The body was not interred. Patsy was looking for a suitable place for her husband’s remains. Perhaps she was looking for the highest bidder?

Thorpe’s remains ended up in a memorial park in a small town in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania, a place where Thorpe probably never set foot. Two small towns that were looking for a way to attract tourists agreed to merge and rename themselves Jim Thorpe, Pa., and construct a memorial park.

Maraniss, responsible journalist that he is, doesn’t report what’s often been rumored: That Patsy also got $500 cash under the table.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com