Melba Pattillo Beals, one of the nine students who desegregated Little Rock Central High School, once wondered if she'd live to see 17.

"Bombs in the air, bullets through our windows, mobs in the street," said Beals, recalling the chaos of the desegregation crisis in 1957. "You wonder if you're going to make it to 17, 18 and 19. And sure enough, to my surprise, we did. And here we are."

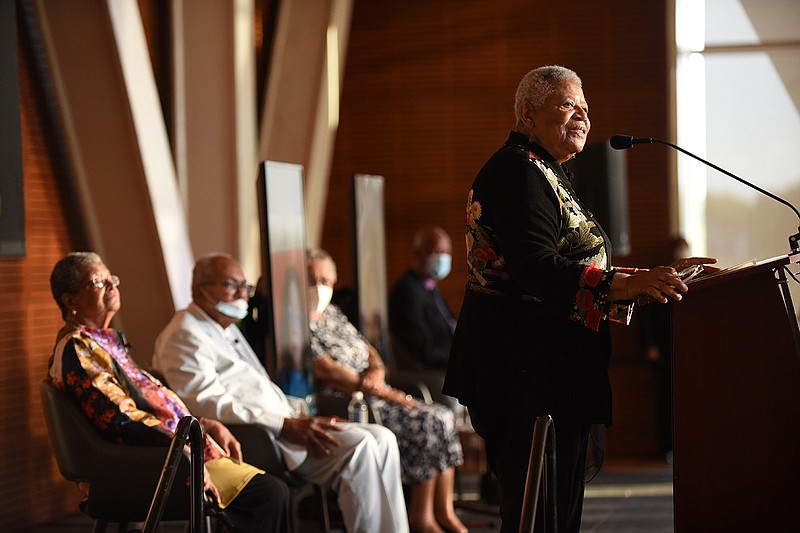

On Sunday, Beals joined seven of the eight surviving members of the Little Rock Nine in celebrating the 65th anniversary of the civil rights milestone. The group gathered in-person and remotely at the William J. Clinton Presidential Center along with speakers and invited guests to commemorate the date.

Remarking on the accomplishments of the Little Rock Nine, former President Bill Clinton charged the audience with a question during his speech.

"Here's what I want you to ask yourself," Clinton said. "What in God's name were we thinking denying these people to live the distinct lives that they live?"

The Little Rock Nine started their first day at Little Rock Central High School on Sept. 25, 1957.

A few weeks before, the students were barred from entering the school by a mob of angry white protesters and the Arkansas National Guard. By sending Guard members to block the students' entry, former Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus defied a federal court order and sparked a crisis that drew national attention.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded by ordering U.S. Army soldiers to escort the Little Rock Nine to school.

During his speech, Clinton said one of the fundamental errors behind the world's problems -- including racial segregation -- is the belief "that our differences are more important than our common humanity."

"We are recreating a drama that is as old as human history," Clinton said. "We may think 65 years is a long time -- it's a blink of an eye. Every time we see [the Little Rock Nine] and listen to their stories, it should remind us that we all have an obligation to say hey, we are different, but it's our differences that make life special because they're built on our common humanity."

Of the surviving members of the Little Rock Nine, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Terrence Roberts and Minnijean Brown Trickey attended the event in person. Carlotta Walls LaNier and Beals attended virtually. Thelma Mothershed Wair was unable to attend the event because of a family engagement.

Those gathered for the anniversary took a moment of silence for Jefferson Thomas, a member of the Little Rock Nine who died in 2010.

Eckford took to the podium to encourage young people to define themselves on their own terms. While speaking about a famous photograph taken of her during the desegregation crisis, Eckford said the stoicism she displayed in the face of an angry mob "is what you see when you're trying not to crack."

"I want young people to understand that they need to know themselves so other people can't tell them who they think they are," she said.

In prepared remarks read aloud for Wair by Spirit Tawfiq, spoke on the merits of a good education.

"Decide for yourself what you want to do when you are older and then go out and get the education you need to achieve it," Wair wrote.

Trickey urged action against injustice by speaking out and read a song she often sings with students to memorialize the desegregation.

"Ordinary people can do extraordinary things," she said while reading the final lines of the song. "Don't be silent, don't be afraid. You may be someone's hope someday."

Some members of the Little Rock Nine reflected on the advances the U.S. has made in civil rights since the desegregation era.

Karlmark recalled how a young girl recently asked her "what was it like?" While Karlmark said she initially didn't understand the girl, but she later realized the question spoke to the gulf between the 1950s and the present day.

"That young girl was proof of what we wanted to accomplish by going back to school," Karlmark said. "That young girl, she didn't know what it was like to be living and Black and studying inside Central High School. She probably didn't even know what it was like to be living and Black on the streets of Little Rock back then."

During his speech, Green remembered growing up on 21st Street.

"Sixty-five years ago, these streets were unpaved. They even hung us in effigy. We only saw the pain of our presence," he said.

In a nod to a street renaming ceremony earlier that afternoon, Green said he now could look at a street "with our names on it."

LaNier echoed the sentiment, saying that while students during her day had tried to walk over the Little Rock Nine, today's students would "walk over us but in a good way."

Earlier Sunday afternoon, members of the Little Rock Nine renamed South Park Street, which runs in front of Little Rock Central High School. With scores of onlookers gathered on the street, the members unveiled a sign reading "Little Rock Nine Way."

"Today we honor those nine young students who just wanted to go to school," said Bruce Moore, Little Rock city manager, in a speech before the unveiling. "From this day forward, the over 2,000 students who attend Central High each day will see a new street sign, a street sign that symbolizes courage, perseverance and grace."

Rodney Slater, former U.S. secretary of transportation, said the street name memorialized the "sometimes stony road of history" the Little Rock Nine had to travel. Speaking after the unveiling, Slater urged the crowd to follow the path cut by the former students.

"We challenge ourselves to be as they are and they were," Slater said. "To go forever forward with determination, to never yield ... to ensure that our best days are yet to come."

During their speeches Sunday evening, some of the members of the Little Rock Nine noted that the fight they'd begun 65 years earlier was still incomplete.

Roberts pointed to the long history of Black oppression in the U.S. and the "institutions, philosophies, practices and ideologies" that continue to hinder civil rights progress.

While at the podium, Gov. Asa Hutchinson said he is regularly reminded of the Little Rock Nine by the bronze statue of the students that sits at the state Capitol. Looking at the statues from the window of his office, Hutchinson noticed that all of faces on the statue are turned toward him.

"The person in the office at the time had denied them entry into Central High School," he said. "And in perpetuity, the Little Rock Nine are keeping an eye on those that exercise the power [of that office]."

Little Rock Mayor Frank Scott Jr. recalled how Woodrow Mann, then mayor of the city, had demonstrated courage during the desegregation crisis by calling on Eisenhower to intervene.

"Some thought he was crazy, but he had his 'such a time as this moment' when he called President Eisenhower," Scott said. "We all have our own 'such a time as this moment.' The question is: 'Will you answer the call?'"