One fine September, 100 years ago, Little Rock's city court judge abruptly resigned after ... some incident ... at White City park.

What was it? I don't know. The old newspapers won't tell me.

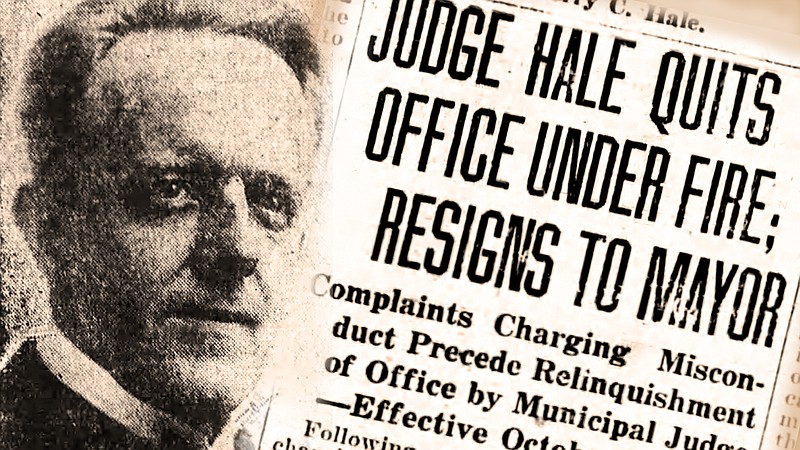

Friend Reader should be familiar with his name, because he appears in these columns often enough: Municipal Judge Harry C. Hale.

The name also might sound familiar to Casual Reader because there were other Harry Hales in the news in 1922 — in particular, Maj. Gen. Harry C. Hale, a national war hero who sometimes took the cure at Hot Springs. This Harry was not that Harry.

This one was younger than the general and had been a very active Little Rock lawyer beginning in 1906, when he graduated among a good class of "young limbs of the law" from the University of Arkansas Law School in Fayetteville.

In 1922, Harry C. Hale was municipal judge. But earlier he held other elective city positions, beginning with city attorney in 1910. A popular young campaigner, he won two terms. So, he was city attorney for four years. Then he was deputy prosecutor for four years, followed by almost four years as municipal judge.

When he first ran for city attorney, he introduced himself to voters in a letter published by the Arkansas Democrat on Nov. 21, 1909. He said he was born and raised in Missouri (in Shelbyville). He did not mention that his father, James C. Hale (1837-1904), had been a judge and a newspaper editor there, for a time editing the Shelbina Democrat. Harry C. wrote:

"Appreciating the advantages offered to young men by the State of Arkansas, I came to Little Rock and secured a clerical position in a railroad office. While so employed I entered the University of Arkansas Law School in 1904 and graduated from there in 1906. Took the bar examination in 1905 and have been practicing law since."

I quite like his campaign slogan: "Competent and Appreciative."

While at school in Fayetteville, he was a charter member of its new Augustus Hill Garland chapter of Phi Alpha Delta, the legal fraternity. Other founding members were Fred Clark Jacobs, Thomas O. Summers, James Kirby Riffel, William Russell Rose, Horace Earle Rouse, Ashbel Webster Dobyns and Hale's future law partner, John Bruce Cox.

Other things we know about Hale from many news reports, social notes and classified ads:

He liked dogs and had a fox terrier puppy while living at 220 E. Fourth St. He survived a "serious operation" in 1909. He could sing and took part in community theater and musicales. He was teased for being a big fan of sometime presidential aspirant Rep. Champ Clark (D-Mo.), speaker of the U.S. House; and Hale wrote elaborate appeals to Little Rock's City Council asking for a vacation to attend the national Democratic convention in support of Clark. But Hale also loyally supported Woodrow Wilson's nomination for the presidency.

While city attorney, Hale nominated Scipio Africanus Jones to sit as a special municipal judge in a case in which Judge Fred Isgrig recused himself (see arkansasonline.com/926tom), and Hale may have been forced into fisticuffs with a white lawyer who objected to elevating the Black lawyer.

Hale also backed Mayor Charles E. Taylor's powerful flex against vice, to shut down the city's red light district and oust its brutal traffic judge, W.M. "Mack" Tweedy (see arkansasonline.com/926boo and also arkansasonline.com/200/1913).

Harry C. also did the city a service that remains useful to historians: He put about three years into revising the city statutes book, in 1915 publishing Digest of the City of Little Rock, Arkansas: Embracing the Ordinances and Resolutions of a General Character Passed by the City Council of Said City up to and Including the Session of September 21, 1914. (see arkansasonline.com/926code).

As municipal judge, he fined himself $5 for parking his car more than an hour on Main Street in October 1920.

And like his buddy Isgrig, Hale vocally opposed the Ku Klux Klan.

As Kenneth C. Barnes beautifully explains in "The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas," a book everyone should pick up (arkansasonline.com/81joe), in the summer of 1922, the second, commercial version of the Klan started throwing its weight around politically. Casting itself as morals police and all-in for Prohibition, this Klan appealed to churchgoing Protestants and other citizens who were sick of the devastation wrought by alcohol abuse and crime in Arkansas.

On Sept. 13, 1922, after something that caused a disturbance at White City, the popular amusement park in Little Rock's Heights neighborhood, he submitted his letter of resignation effective Oct. 1 to Mayor Ben Brickhouse.

■ ■ ■

So, what happened in the park?

The closest the Democrat, Little Rock Daily News and the Arkansas Gazette come to divulging details appears to be a Sept. 13 report in the Democrat:

"Trouble on the dance floor at White City last Monday night between Judge Hale and the management of the park, and also between Judge Hale and Patrolman B.F. Morrison and Deputy Sheriff Clifton Evans, formed the basis for the complaints, it was understood, although Mayor Brickhouse and Chief Rotenberry declined to discuss the matter."

The Gazette report Sept. 14 added the information that a complaint against Hale was lodged "informally" by a member of the City Council, that his conduct was "boisterous and unseemly" on the dance floor. Brickhouse had decided to submit it to Chief Burl Rotenberry's Police Committee for review; but when told of that plan, Hale immediately resigned and the charge was dropped.

All three papers noted there was a chance Hale would move to California, where he had a job offer.

The municipal judge post paid $3,000 a year, but it required the judge to devote his full time to the office.

Replacing the judge required that Gov. Thomas McRae authorize a special election; but by Sept. 17, McRae had failed to do so, claiming that he could not until someone formally notified him Hale had resigned. And on Sept. 18, friends of Hale mounted a defense of his character to the council.

The Daily News reported that the Rev. Harry G. Knowles, Hale's pastor at First Christian Church, spoke for him, as did the Rev. John Van Lear, pastor of First Presbyterian Church, and Alderman Isgrig. All pleaded with the council to withhold judgment until Hale had a chance to vindicate himself.

"Judge Hale addressed the caucus," the News reported, "admitting the truthfulness of some of the charges against him, none of which seem to be any more serious than frivolous conduct, and promising that in the future he would conduct himself [in a manner] that would merit the entire approval of the public."

The council then agreed with Alderman George Gay's motion to postpone their decision for a month. Only one alderman demurred, H.B. Chrisp of the Ninth Ward, who happened to be the Klan-approved candidate for county and probate clerk. The Klan then took out ads announcing a meeting to discuss why the council hadn't accepted Hale's resignation.

On Sept. 24, Hale sent his resignation letter directly to McRae, and the governor accepted it and set the election to coincide with the General Election Oct. 3. Four candidates stepped forward. Three guesses who won.

The Klan-backed candidate, Troy W. Lewis, polled 4,400 votes; his nearest rival received 408.

What happened to Harry C. Hale after his name just about vanished off the face of Arkansas newspapers in 1922? That, I do know. Tune in next week.

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com